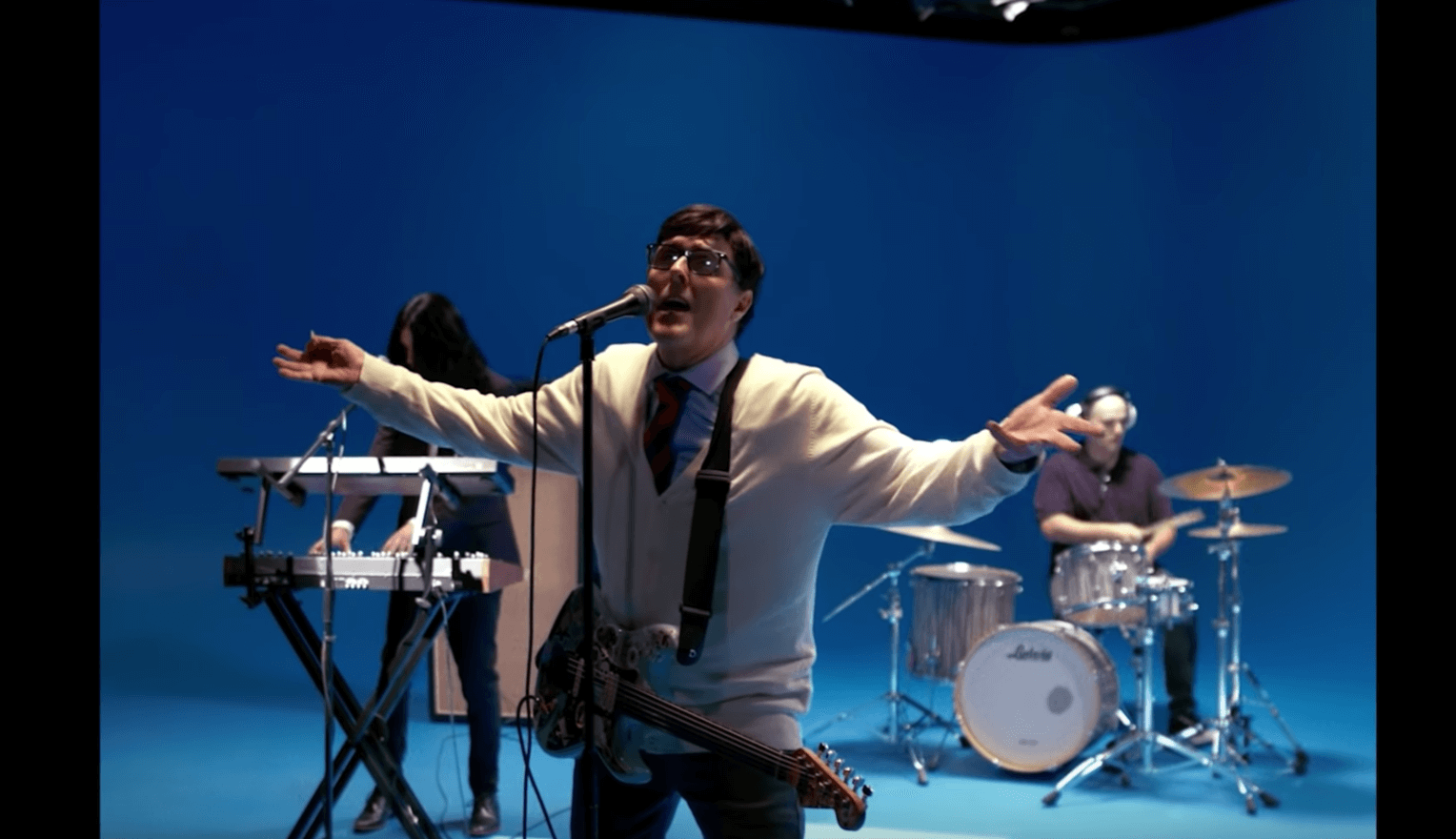

Two awards-season frontrunners just won’t die: Green Book and Bohemian Rhapsody. Perhaps you saw them.

Green Book is about Italian-American Tony Vallelonga escorting black pianist Dr. Don Shirley on a road trip through the Jim Crow south. Bohemian Rhapsody is about late Queen frontman Freddie Mercury. Both movies have seen a ton of attention throughout awards season, each receiving a Best Picture Oscar nomination this week.

So why are both movies embroiled in controversy, and if they’re earning so many awards, why do people seem to hate them?

The least important answer is this: Of the awards-ballot favorites this year, Green Book and Bohemian Rhapsody are generally considered the two worst movies. Review aggregate Metacritic, which assigns movies a score based on their degree of praise (rather than Rotten Tomatoes’ more simplistic “positive or negative” measuring stick), gives Green Book a 70 out of 100 (indicating “generally favorable reviews”—critics liked the movie, but didn’t love it). Bohemian Rhapsody, meanwhile, sits at a paltry 49 (most critics thought it was just okay).

For comparison, other Best Picture nominees score as follows: Roma – 96, The Favourite – 90, A Star Is Born – 88, Black Panther – 88, BlacKkKlansman – 83 and the polarizing Vice at 61. Even with that last score included, Green Book and Bohemian Rhapsody sit at the negative end of the review spectrum. Cue cries of “undeserving” and “overrated.”

However, the backlash against Green Book and Bohemian Rhapsody becomes more serious when we evaluate each movie on their own merits. Both are based on a true story, but both have troubling relationships to those histories.

Green Book presents Dr. Don Shirley as a man out of touch with his black identity. The musical prodigy grew up in an apartment above Carnegie Hall, and Green Book positions his upper-class background at odds with the lower-class black communities he sees on his journey through the South with Vallelonga. This tension is real for many minorities who live apart from the cultural foundations of their people—Shirley is shown in the movie to be uncomfortable at a black-friendly motel, and his character is ignorant of figures like Aretha Franklin or Little Richard. At one point, Vallelonga introduces him to soul food, specifically fried chicken, in a scene many of the movie’s detractors hold up as problematic.

Most significantly, Green Book says Dr. Shirley is cut off from his own family, a circumstance that his real-life family has vehemently denied. In fact, Vanity Fair reports Shirley was the best man at his brother’s wedding in 1964, two years after the events of Green Book took place.

It’s not the only thing disputed—you can find more detail here—but there are greater problems at work than inaccuracies. Vanity Fair’s K. Austin Collins explains it like this:

[lborder]It’s one thing to get historical facts wrong, or to massage them for the sake of dramatic coherence. It’s another thing entirely to take something so essential as racial identity—as the inner life of a person of color—and revise it…

Imagine revising a black man’s feelings about his identity relative to such violent currents and racial antagonism [as in the Jim Crow South]. You are fundamentally revising an essential political fact of who that black man is. You are re-writing the story of how he feels about his race at a time when that race could not be more of a cultural or physical liability. You are, in effect, re-writing that identity. This is, to my mind, a fairly brash thing for a white filmmaker to do—and to do it so casually, so unknowingly, to boot.

This goes beyond “a white man telling a black man’s story.” Nick Vallelonga, Green Book‘s screenwriter and the son of Tony, is the mind behind this portrayal of Shirley. Peter Farrelly, the (white, it must be said) director, is the vision. Both men have disturbing decisions in their past.

In 2015, Vallelonga tweeted in agreement with Donald Trump that Muslims in Jersey City cheered when the World Trade Center fell on 9/11. That claim has been proven false, and Vallelonga has apologized to the public and to the Green Book crew (Mahershela Ali, who plays Shirley, is Muslim).

Farrelly has been in hot water since a 1998 Newsweek story resurfaced which holds accounts of the Dumb and Dumber cast saying Farrelly would flash his genitals at them “as a joke.” Since the story’s been recirculated, Farrelly has apologized and confirmed the accounts are true.

That’s Green Book. That’s why people aren’t exactly cheering for it to win any Oscars.

Bohemian Rhapsody is another affair entirely. Most prominently, its director Bryan Singer has long been accused of sexually assaulting and harassing underage boys. This week, The Atlantic published a long, disturbing feature in which four more men come forward and share stories of Singer abusing them.

Singer was fired from Rhapsody two weeks before the end of production for inappropriate behavior, but he’s still credited the director. In fact, he’s received some awards nominations for his work despite his on-set behavior and his history of abuse allegations.

That’s reason to not award Rhapsody certain production awards, but there are still issues with it as a biopic. Freddie Mercury’s sexuality was an unavoidable and inseparable part of his person and persona, and the movie buries it. Many people take issue with this not only for the representational misstep, but also for the simplicity with which it treats a very complex man.

Perhaps you point out that there’s nothing wrong with a Freddie Mercury movie being only interested in his musical career, but Rhapsody opponents point out that Mercury’s fluid sexuality was as integral to his music as anything else pertaining to Queen (Queen! The band was called Queen!). They argue you can’t separate one from the other, and for Bohemian Rhapsody to do so not only makes for a less interesting movie, it makes for one that isn’t truly honoring of its central figure.

Despite all of these critiques, both Rhapsody and Green Book have persisted as huge awards-season players. In fact, Green Book has decent odds to win Best Picture, and both movies have taken home lots of hardware already this winter. Trophies for famous people don’t matter, but they can reflect what we as a culture value in art, and that means honoring each of these movies does carry some degree of import.

Watching how the Academy decides its winners in February will, in that way, reflect just a little bit more than the best movies of the year. It will reflect what circumstances and contexts we think are important when considering valuable art.