Like most people, I was nervous when I first heard about the medical emergency that put Rachel Held Evans in the hospital, but I didn’t fear the worst. It seemed impossible. She had just tweeted about Game of Thrones a day or so earlier. She’d be fine. But the updates were sparse and bleak, filled with worrisome and vague medical terms. Perhaps this was serious. But the idea of her actually dying seemed so implausible that it barely even occurred to me.

Even hearing the news of her death Saturday, it didn’t feel real. It wasn’t until I was crying in an Uber on my way to the airport that it sunk in: Rachel Held Evans has died.

Evans was a singular soul; a refuge for the disenfranchised and doubtful. She saw the millions that had been harmed in Jesus’ name and assured them she didn’t blame them for their hurt and anger. She implored them to try Jesus again, because Jesus was better than they’d been led to believe. The gap she leaves behind is immense because of the immense amount of energy she invested into the Church. She loved it with all her heart.“This is what God’s kingdom is like: a bunch of outcasts and oddballs gathered at a table, not because they are rich or worthy or good, but because they are hungry, because they said yes,” she wrote in Searching for Sunday. “And there’s always room for more.”

Her legacy is too vast to be summed up simply but that idea — of there always being room — feels close to the heart of Evans’ life work.

Her critics, of whom she had many, called her angry, cynical and divisive but she was none of these things. Well, maybe she did get angry sometimes, but only because she gave herself permission to speak the evangelical system’s faults out loud while many others preferred to ignore them. Evans was mad that so many people wanted to make God’s Kingdom small, and she rallied a lot of other people to be mad about that, too. It’s just one small part of her legacy, and a lovely one.

But cynical? Divisive? Hardly. Evans believed in the Church and fought for it with relish, bracing herself against the doors as others tried to shut them, insisting to those on the outside there was still plenty of room. Reading her books, you see someone who loved being a Christian and wanted everyone to know just how good the Good News was. She wrote God loved you and anyone who said otherwise didn’t know what they were talking about. She wrote mainstream Christianity had lost its way, but the real thing still existed and was worth reclaiming. Evans wasn’t enamored by certitude about God (“I still believe in Christianity because it’s the only story I’m still willing to be wrong about,” she wrote). She just loved Him.

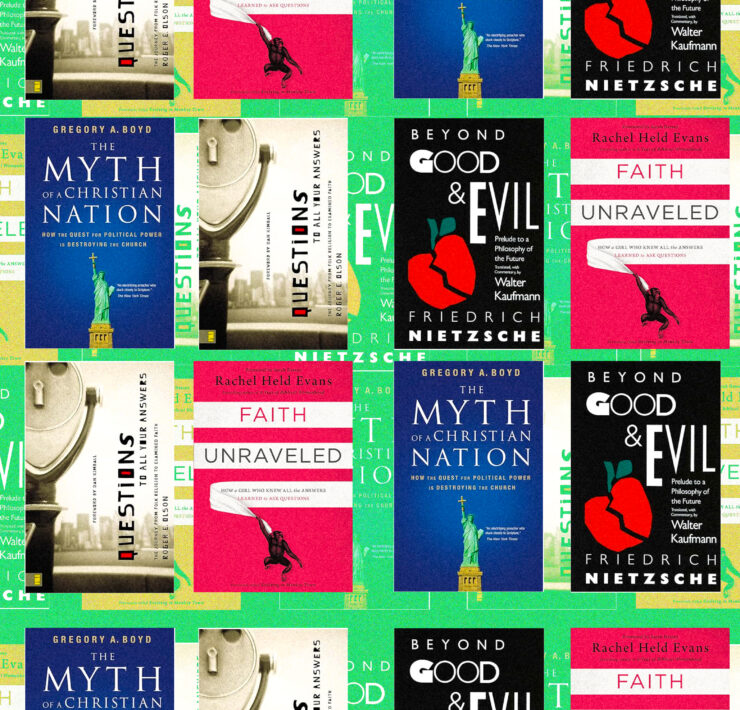

Evans didn’t equate loving God with soft-minded sentimentality. She was a nerdy bookworm, a small-town Tennessee wife and mom with a passion for biblical theology that should have embarrassed those who accused her of intellectual laziness. She was relentlessly curious, and allowed herself to ask the questions others raised in her tradition feared. She sought answers from experts, books and people with less privilege than herself.

The way she asked questions gave other people — especially women — permission to ask them, too. It’s impossible to know how many women applied to seminary because of her, but Twitter would suggest it is not a small number. Those women will inspire other women, and so on. Another part of her legacy.

She had a keen understanding of how theology manifested in real life — how the nuances of what you believed about the Bible should affect the small parts of your life, like where your kids go to school and how to think about criminal justice reform. She was political, but only because she was theological, and she believed theology had ramifications for politics.

But even as the political climate grew more tense and contorted, Evans was a character study on how to stand firm in your every conviction while still retaining patience and grace for those who disagreed. A Twitter user recounted how in one Q&A session, Evans said when she felt herself getting heated with her online critics, she would imagine them on their living room floors, playing with their children. She didn’t believe in compromising on her convictions, but she also didn’t believe in dehumanizing her opponents.

All these things point to her courage, maybe her most obvious trait. Evans was fearless. Most writers enter an existing space and attempt to add something new, but Evans did not have the luxury of an existing space. She had to carve it out with her bare hands, and figure out how it worked as she went along. That meant she made mistakes sometimes, and would apologize when she did (Evans never got enough credit for her willingness to apologize) but it also meant a lot of people who weren’t sure there was a place for them in Christianity were able to find one — because Evans built it.

I went through airport security wearing sunglasses because I was embarrassed about my tears. As I made my way toward the gate, I saw a small, interfaith chapel with a little stained glass window, a few cheap pews and a spiral-bound notebook on a bench to write down prayers and blessings. A little engraved sign at the door said “All Are Welcome” and I thought the place felt oddly appropriate for what was on my heart. I scribbled a quick prayer for the Evans family in the notebook. As I did, an old woman sat down nearby and asked, in broken English, if I minded her being there.

“Of course,” I said. “There’s always room for more.”