When I was a teenager, Christian rock was almost my religion. I don’t remember picking up the Bible of my own volition, but an entire wall of my bedroom was plastered with five years’ worth of magazine clippings of my favorite Christian band. And I don’t think it was all that wrong, to be honest. I needed something to revere, and these bands got me thinking about all kinds of ideas that I needed to be thinking about, and stuff that still matters to me to this day—love, mercy, justice, death, life, hope, joy, God—so I’m not really worried this was sacrilege. Yes: I was a Christian rock fundamentalist.

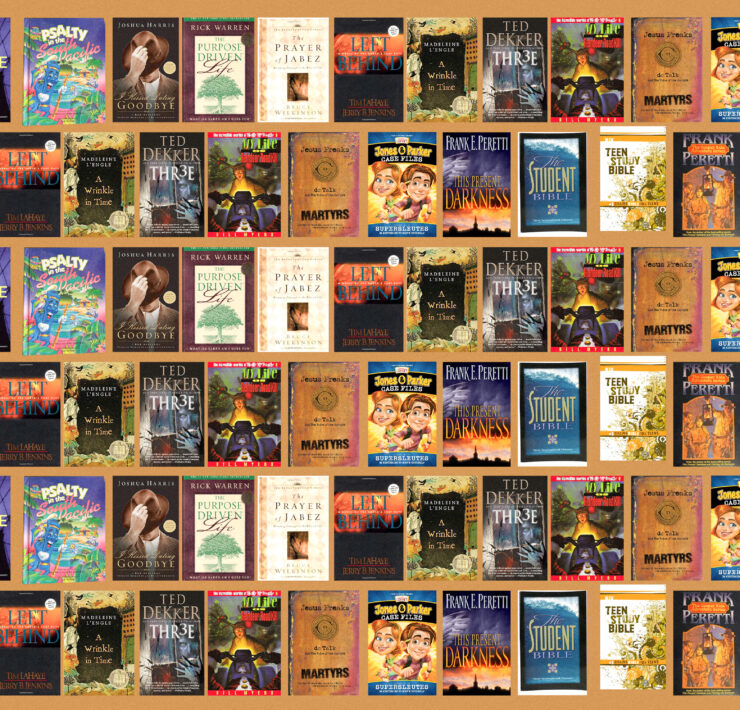

I hadn’t heard of record labels like Kill Rock Stars or Sub Pop, but could rattle off the name of every band on Tooth and Nail or Five Minute Walk. I bought Poor Old Lu (not Nirvana) records, read Seven Ball (not Spin), and listened to a syndicated radio show called Z-Jam (not Z-Rock, which was just down the dial). Rock and roll was part of a package that included church, teen study Bibles, youth group, prayer and evangelism. Yet for all that, I don’t think I was ever a Christian fundamentalist, because I don’t see myself in those stories—sometimes hilarious, sometimes heartbreaking—by the long list of thirtysomething artsy, writery types who grew up fundie and had the spiritual rug pulled out from under them the minute somebody asserted that maybe Adam and Eve weren’t literally the first two real human beings. Everything is thrown into doubt, and cynicism and atheism follow close behind. Though my understanding of Christianity has changed over the years, that is not my story. I did not “lose my religion.”

But I can remember the exact moment I lost my faith in Christian music.

—

In the 1990s, if I was at a Christian concert, it’s a good guess that Audio Adrenaline were the opening band. I’m not sure why they remained a warm-up act for so many years, but I saw them open for dc Talk and the Newsboys about a hundred times each, tour after tour. ForeFront Records played up Audio Adrenaline’s rock-rebel image; a genius move was releasing a live AA album under the title Live Bootleg, the cover of which displayed a maximum rock-and-roll-style black-and-white photo of a band member headbanging in a totally righteous way. There was nothing bootleg whatsoever about this record—it was a legitimate release on a major label. And Audio Adrenaline didn’t even have a drummer on their first two records, but they were marketed, at the time, like an ultra-rebellious grunge band. If you had to compare them to a regular rock band (and, yes, you had to), you probably would have called them a “Christian Spin Doctors.” Their ubiquitous Christian radio hit, “Big House” (about heaven, not jail), had the same sloppy four-chord party vibe as the Spin Doctors’ “Two Princes,” right down to the goofy scatting.

Audio Adrenaline concerts in those days were heavy on jumping around and shouting, especially on their Christian party anthem (yes, “Christian party anthem”) “We’re a Band,” the chorus of which is: “We’re band! We’re a band! We’re a band!” Audio Adrenaline were, without a doubt, a band. And so their betrayal hurt worse than almost anything I can imagine a Christian band having done.

I don’t mean to place the blame squarely on Audio Adrenaline. This story could be repeated with almost any mainstream Christian rock band in the 1990s, at any concert. But here’s what happened: In the middle of a show, after 45 minutes or so of sweaty headbanging and singing about how They Were a Band, Audio Adrenaline called for a time-out to talk to the audience about Jesus. This wasn’t at all uncommon at Christian concerts—the Christian kids in the crowd happily tolerated it, even though we rarely went up for altar calls. But when one of the band members stepped up to the mic, my life changed. And not in the way the band intended.

“I just want to tell you something,” he said. We got quiet and reverent. “This music that we play—it’s a trick.” He went on to explain that the only reason they played rock music was to get our attention and tell us about accepting Jesus Christ as our personal savior. Jesus loves you, he said, and He wants to have a relationship with you. The music is secondary, not the point; it’s a trap. It doesn’t matter.

It doesn’t matter.

I was stunned. It doesn’t matter. The stuff I care about most doesn’t matter.

I was confused, then angry. How dare you make me care about this music so much, then? How dare you, everyone, Christian record labels and radio and bookstores and bands and youth groups, how dare you make me fall in love with rock and roll and then tell me it’s a farce, tell me that the only reason it’s marginally OK that I’m listening to it is that behind it all is the Right Thing to Believe. I already believe it! Can I just have the music? And you, Audio Adrenaline, you said—you just said, a few minutes ago, in a song, over and over and over, that you were a band. A band!

I had tolerated many lame subcultural trappings for this music I loved, but I would not tolerate a band lying to me. This was the beginning of the end of my teenage love affair with Christian rock—but I’m not bitter. This was a push I needed, a felix culpa that would eventually open up a world in which God could be experienced in a thousand places that were not a church and a thousand songs that were not praise choruses. Once, I didn’t think such a thing was possible.

I suspect many of us have reached that realization, at one point or another. And you might have a similar story. My story continued as I developed ears to hear traces of the holy in everything from Jeff Buckley to Sunny Day Real Estate to Blackalicious to Sigur Ros. And in a way, I guess, I owe it to a band who insisted, for a moment, that they weren’t a band. Even though they totally were.

Have you had an experience like this? Where do you hear traces of the holy?

Joel Heng Hartse has written about music for Paste, Geez, Blurt, Christianity Today, Beliefnet, the Stranger and Killing the Buddha, among other publications. His new book, Sects, Love, Rock and Roll, from which this is adapted, is available now from Cascade Books.