The first and most familiar of the so-called Slow Movements was the Slow Food movement which began in Italy in the 1980s, with a group that opposed the construction of a McDonalds near the infamous Spanish steps in Rome. Not only did this group renounce fast food, they also worked diligently to promote an alternative, locally crafted foods that were distinctive of the various regions of their Italian homeland. They defended the culture of the table, the pleasures of taking our time enjoying good food with family and friends. The Slow Food movement spread outward from Italy over the last three decades and now has chapters in over 150 countries. More recently, other Slow movements have emerged: Slow Cities, Slow Money, Slow Parenting, Slow Fashion and others.

There are many reasons why these Slow movements should be of interest to us as Christians; one of the most compelling is that in our speed, we are rapidly losing the capacity to be attentive to and present with others, as God was present with the Israelites throughout the Old Testament and as Jesus was present with his disciples and followers. A pressing question of our times therefore is: how do we begin to imitate the presence and attentiveness of Jesus in a culture that is marked by rampant inattentiveness?

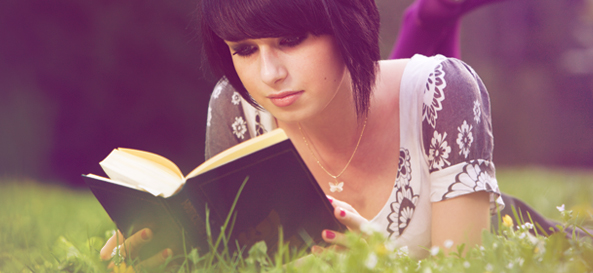

For me, poetry is a practice that is helping me begin to slow down and become more attentive. Learning to read a poem carefully trains us to pay extraordinary attention to the sounds and images of language that we might easily overlook in our haste. It is not surprising, given the value that our culture places on speed and efficiency, that poetry is not a particularly popular art-form these days; poetry books for instance are very rarely bestsellers. Poems offer us an invitation to abide with their words.

Often, the poet is offering us an image for our consideration, holding it up and allowing us to look it from many angles. The image may (or may not) come into focus as we read the poem slowly and re-read it again and again. Consider one of my favorite poems, Emily Dickinson’s “Hope is the Thing with Feathers.” A careful reading of the poem challenges us with the question of what hope is? Dickinson observes that hope is like a bird whose song is heard most sweetly in the storms of life. Hope not only offers its comforting song to us, but never asks or demands anything from us, not even a crumb. Dickinson’s words and images, like those of any superb poet, stir up wave of further questions: what image would I give to describe hope?; how am I being an envoy of hope to others, offering comfort in the storms of life and not asking anything in return? Such questions are the beginning of a potentially long conversation with the poem.

We may need to bring out some tools—some resources about the poet or the particular poem—that help to bring it into focus. In reading Dickinson’s poem, we have to remember that it was written long before the invention of radio, television or the internet. Birds and their songs were paid attention to and were part of the beauty and entertainment of the day. Reading this poem today, I am reminded of how oblivious we are to much that goes on in the world around us, and particularly things like birds that previous generations might not have been as likely to miss.

In some poems we are swept away by the vivid imagery that the words create in our minds – regardless of whether it was intended by the poet. Consider C.S. Lewis’s poem, “To Sleep,” for instance. Our minds could get swept away with his imagery of a dark and mysterious forest in which “light and shadow interlaced,” and yet at some point we are yanked back into the poem and realize that this forest is the world of sleep.

Finally, we should also be attentive to the sound of the poem: the meter, the rhymes, alliteration. I remember memorizing Lewis Carroll’s poem “Jabberwocky” in middle school, and how the sounds of the words, many of which were nonsensical, clung fast to my memory. Some of the sonic elements of poems will require diligence for us to recognize; it takes a careful ear to recognize them.

Like a rich and carefully crafted dessert, one must savor a poem in order to enjoy it fully—its images, its context, its sounds. A good poem is hospitable, inviting us to sit for awhile and enter into a conversation. Poetry, however, does not come naturally for us in our times; it is a discipline to which we must commit ourselves. If we wish to sharpen our attentive faculties through poetry, there are a number of resources that might be helpful. First, we might turn to the poetry of the psalms, as many of our fellow Christians have done in churches and monasteries throughout the last two millennia. If you would prefer to focus on more contemporary poetry, there are services like Everyday Poems that will send a poem to your inbox every day. Similarly, The Englewood Review of Books typically shares a poem of the day through Facebook and Twitter.

There is much to lament in the speed and inattentiveness of Western culture today, but the Slow movements are a step in the right direction. I am hopeful that by submitting ourselves to disciplines like Slow Reading, we can train our attention and become the attentive people that we have been called to be, bearing witness to Emmanuel, the God who is always present with us in Jesus.