Thanks to his frequent blockbuster collaborations with Jim Carrey, director Tom Shadyac was on top of the comedy world. Starting with the two Ace Ventura films and moving on through Liar, Liar and Bruce Almighty, Shadyac had a Midas touch at the box office.

But then in 2007, he experienced a double-whammy when his Bruce sequel, Evan Almighty, became one of the biggest comedic box-office bombs of all time, and then he later suffered severe head trauma in a bicycle-riding accident. The side effects included blurred vision and severe migraines that never seemed to go away. Shadyac—who had been a lifelong Catholic—thought he was going to die.

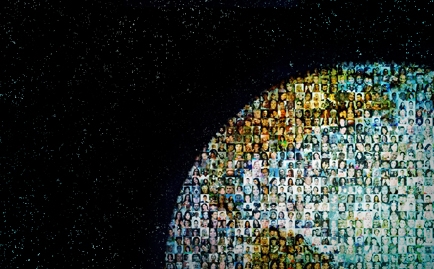

Then suddenly, his life-threatening symptoms miraculously healed, and Shadyac decided to radically transform his lifestyle. He embarked on a spiritual and philosophical quest that took him around the planet while he explored the answers the various world religions and most famous philosophers had to offer. As a result, he wound up feeling that his wealth and extravagant professions were a form of mental illness in a world where millions of people go to sleep hungry every day.

Shadyac decided to take radical measures to change his life and his mindset, and wound up selling off his land and his house—as well as his private jet—and downsized to live in a mobile home at a community on the Malibu coastline. He gave away most of his wealth, but also spent $1 million of it to finance a highly personal documentary called I Am, which put his quest on film and offers a heady yet often compelling mix of insights and analysis into the meaning of life and whether there’s an afterlife.

Shadyac sat down with RELEVANT recently to discuss his films and their meanings.

Of all the great thinkers you spoke to, all but one of them hadn’t seen Ace Ventura: Pet Detective? That’s outrageous!

Shadyac: I agree. I agree! What is wrong with these people? They’re just busy solving apartheid, writing A People’s History. Chomsky was on a different path, man. When he was 12 years old, I think he was writing his first book about the Spanish American War while I was watching Brady Bunch reruns and snacking on Cheetos. But that’s why they’re doing the work they do. I was surprised and wonderfully fine with it. I think it was the way that ego left the room. We all want to come with our resume—I’ve written this, directed that—and they had no idea what it all was. So I was dealing with them without the crutch.

What I found interesting was that you start the film asking what’s wrong with the world and what do we do about it, and then you turn the tables and ask what’s right with the world and everything in it. Were you a person who was glass half-full before the project, and what do you consider yourself now?

Shadyac: I think both perspectives—half-full, half-empty—can be valuable, but I just want to know what’s the truth. Truth can be a matter of perspective, but I also think there’s a truth that exists, that there are laws to the universe the way Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King believed. I moved from hope to faith. Hope is the belief we might get it done, and faith is the knowledge we will get it done. When you see the underlying story of who people really are and what the nature of reality is, I think it tells a very positive story.

For you, having gone through a tragedy yourself to motivate you on this path, what do you think society will need to move forward?

Shadyac: That’s why M. Scott Peck defined laziness as the first sin in the Garden of Eden. What you put off today you’re going to have to deal with at some point. We’ve put it off long enough. I had to deal with my own near-death, which is a classic dark night of the soul experience. I think we’re seeing death in the world around us, the death of the natural world, and we’re seeing such problems that we continue to pollute and to poison. We’re seeing a continual running stream of wars, a continual gap between the rich and the poor, we have an economy that’s broken. I think the crises are all around us. I don’t think an individual has to face their own death, other than their death of perspective and the way they see things. Ray Anderson in the movie says we’re gonna have shock after shock after shock, and we are having that right now. You couldn’t see Egypt coming, but enough people have woken up to the idea of a different way for the Egyptian people, and suddenly, like the Berlin Wall, it fell. We don’t know how many people are shifting their viewpoints, and then one day the ideology like the Berlin Wall will fall.

Some people resist this conversation. Have you run into haters or naysayers as you’ve been doing press?

Shadyac: I wouldn’t say haters, but people who don’t see eye to eye. And that’s to be expected and welcome. My father himself, whom I loved dearly, thought much of my vision might be utopian. My father was a lawyer and used his own life as an argument in court against his idea that it was utopian and that we couldn’t build a compassionate world or business structure because he did it. My father built a huge business—forget charity—that takes care of people first, cures cancer first, ahead of profit motive.

To that end, why did you go almost solely to left-wing intellectuals like Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky—who some accuse of having a negative view of America and its history—and not consult conservative or libertarian thinkers, or Christian thinkers who could put the context of the quotes on love in a way that wasn’t just New Age?

Shadyac: First of all, I don’t think any of the content is New Age. I think it talks about ancient ideologies and ancient ideas. I don’t consider the film liberal or conservative, and I didn’t go to people who were liberal or conservative, but to people who had moved me in some way and helped to change my life. I don’t know if you consider Desmond Tutu a liberal or conservative, or a clergyman or not, but I went to him because he walked in a powerful way that changed me. I didn’t go to Zinn for a left view or a right view, but because he woke me up to a certain kind of history that I was unaware of, and it helped to change me. I never viewed anyone in the film as having a political ideology, and I don’t think the film has a political ideology. It’s about my own personal journey.

I just did an interview with Michael Medved, the conservative talk show host. And we met eye to eye on many of the principles in the film. When you start to look at things politically, that’s where you put walls up. When you look at things in principle, that’s where we build bridges. Michael and I had a wonderful hour on the show—he welcomed me to his home—and we stand differently, but we both edify each other. I see the differing point of view every day when I turn on the TV, and it’s not liberal or conservative. It’s a philosophy that we are all separate, and we’re not brothers and sisters. I happen to believe we are. The human genome research shows we are. We’re all brothers and sisters in our DNA, and I choose to take care of my brothers and sisters. I think it’s that utopia, that this is wishful thinking and I don’t think it’s wishful. Gandhi said he chooses to walk in the meat and marrow of life, and that nonviolent change isn’t wishful—it’s more powerful and it’s a lasting way of getting conflict resolved. When you do something in a nonviolent way, people will die and there will be casualties. But you’re taking a different point of view that has a power. There are many causes I’d die for, and that death will have a power, but I’m not willing to kill you to say that I believe in peace.

There’s a reason we talk about Jesus still today, and it’s not in a dogmatic way. It’s because He said: “No, you cannot kill me. There’s something in the meat and marrow of life, my spirit, who I am—the I AM—that you can’t kill.” We wouldn’t have that story if we took our culturally accepted story, that somebody’s about to kill me, so I’m going to kill them first.

What sort of spiritual practice do you have now? And how does this change affect your career now—are you going back to comedies, are you looking for it and is there a backlash from Hollywood for doing this?

Shadyac: In my experience, the Hollywood people have been unbelievably supportive. My agency doesn’t stand to make a nickel off it, but they’re giving me the use of their screening room, their phone list and client list, people like Will.I.Am and Peter Gabriel who saw the film and were then incredibly generous in giving their songs at a great rate when I couldn’t afford their music normally. I’ll simply tell great stories and will gladly go back to studios, and I want to do stories that affect me. With how I view films, I think films are ways that we talk to each other and we deepen the conversation about who we are. I think laughter is a sacred act. I’d do a comedy again—if you’ve got an idea for Ace 3, I’m all ears.

I’ve been for years doing something [called] Lectio Divino. If I had a previous life, I was a monk or a poet, because I’ll read a poem and meditate on a passage that moves me. I try to eat what I call real food every day, and that’s not buying into what the culture says is cool or wise, but tuning into your heart for truth.