Editor’s Note: The following interview with Noah screenwriter Ari Handel contains some minor spoilers and discussions of items that deal with major plot points in the film.

Even before it released into theaters last week, Darren Aronofsky’s take on the Bible’s story of Noah had been the subject of controversy in the Christian community. Along with accusations that the filmmakers were taking too many creative liberties with the original text, reviewers have debated the use of themes like Gnosticism, judgment, condemnation and even hidden symbolism in the big-screen version of the Old Testament story.

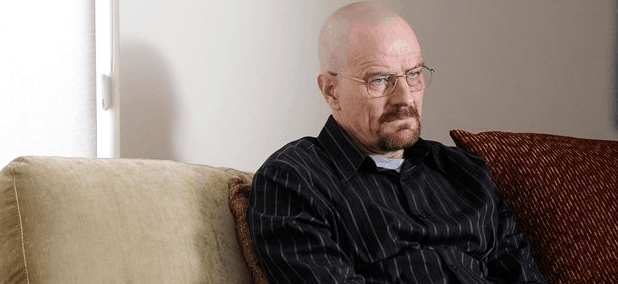

We recently had the opportunity to speak with screenwriter Ari Handel—who co-wrote the script with Aronofsky—to discuss audiences’ reaction to the film, some deeper biblical themes of the movie and the thinking behind Noah’s controversial theology.

Q: How close is this film to your original vision?

A: Very close. We were lucky. By the time we arrived at our final script, we were lucky. We had great actors. Everything went right on set. We didn’t lose much of what we planned. Everything came together.

Q: What’s been the most surprising response you’ve seen to the film so far?

A: I think the most surprising thing is how all over the responses are from all sides. We’ve got religious people praising the film very strongly and also being very upset by it. And we have secular audiences doing the same. It’s really interesting how much debate and power has been stormed up by this film.

Q: A lot of people are saying you took a few too many liberties with the story. Some people are saying you pulled from extra-biblical sources like the Gnostic texts. What would you tell those people?

A: I would say this: We set out very purposefully to upset expectations and change expectations people had about this story. We had expectations when we came to it—Darren [director, Darren Aronofsky] and I, we read Genesis as kids and young adults—but what we had in our minds was a Playmobil ark and as for animals, pet stores. And that’s the way the Noah story has gone into the pop consciousness. It’s a very, very, very different story than what we saw when we opened Genesis again as middle-aged men and thought seriously about what’s there. To get people to grapple with it and to see it fresh, we wanted to break expectations. Some of them we wanted to break that are just incorrect—like the idea of what the ark looked like. It was purposeful.

What I’d tell people is it’s very important to us that nothing we actually did directly contradicted the Genesis story. There are some places where people think we did, and I’d just say, “We didn’t.” It was all grounded somewhere. It wasn’t just the Genesis story the way you expected it. But it’s grounded. Anything we did that isn’t explicitly there isn’t arbitrary. There are themes in the Genesis story that we wanted to dramatize and make people empathize with. It’s there for a reason. I hope people go into it open-minded. When they see things they don’t expect, roll with it a little bit. And see how you feel about the film afterward.

What we want the film to make you think about is the core question of Genesis: The nature of goodness and wickedness in men’s heart, and whether that should be responded to with justice or mercy, the relationship between mankind and the world around him to the sacred. Those are the questions we grappled with.

Q: Can you explain the snakeskin that gets passed from generation to generation? That does seem a little Gnostic.

A: When Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden, it says God gave them a garment of skin—sort of a parting gift from God to mankind as we leave Eden and go out into the world. So we wondered what that was—and as we looked at commentaries about it, one of the common ones was that it was the skin of the snake. We wondered why that would be, and it occurred to us that God made the snake. The snake was good, at first. But then, the Tempter arose through it. In our version, we have the snake shed that skin, and the shed skin is the shell of original goodness that the snake left behind when it became the Tempter. It’s a symbol of the Eden that we left behind. It’s a garment to clothe you spiritually.

Q: I’ve seen some people saying your portrayal of God leans too heavily on the side of justice and condemnation.

A: Look. If you go to Genesis, look how the story starts. God looks and sees that the hearts of man is filled with wickedness, and He grieves into His heart and regrets that He has made them and decides that He’s going to wipe them off the face of the earth. It’s at the end that God says, despite all that, “I will never again have to wipe mankind out.” In fact, if you look at the bookend of the story of Noah, God moves from a very strong place of justice to a place of mercy. Our addition is that we let Noah follow that same path—from a place of justice to a place of mercy. If you look at the Genesis story carefully, I don’t see how you can avoid seeing a very justice-oriented God.

Q: What question would you like audiences to leave your film thinking about?

A: There are two. The story says that we all have goodness and wickedness in us, and it’s up to us to pursue goodness and resist temptation. That’s a personal choice that we all have. We can’t fall into the trap of thinking “those ones” are wicked and “we’re good.” That’s an easy way out.

The second question is, the Noah story is about a second chance. It’s a second chance for the world and a second chance for mankind. One of the questions we hope people come out of the film with is, to remember that we’re living in a second chance. And to ask ourselves, “What are we doing with that second chance? Are we doing well with it?”