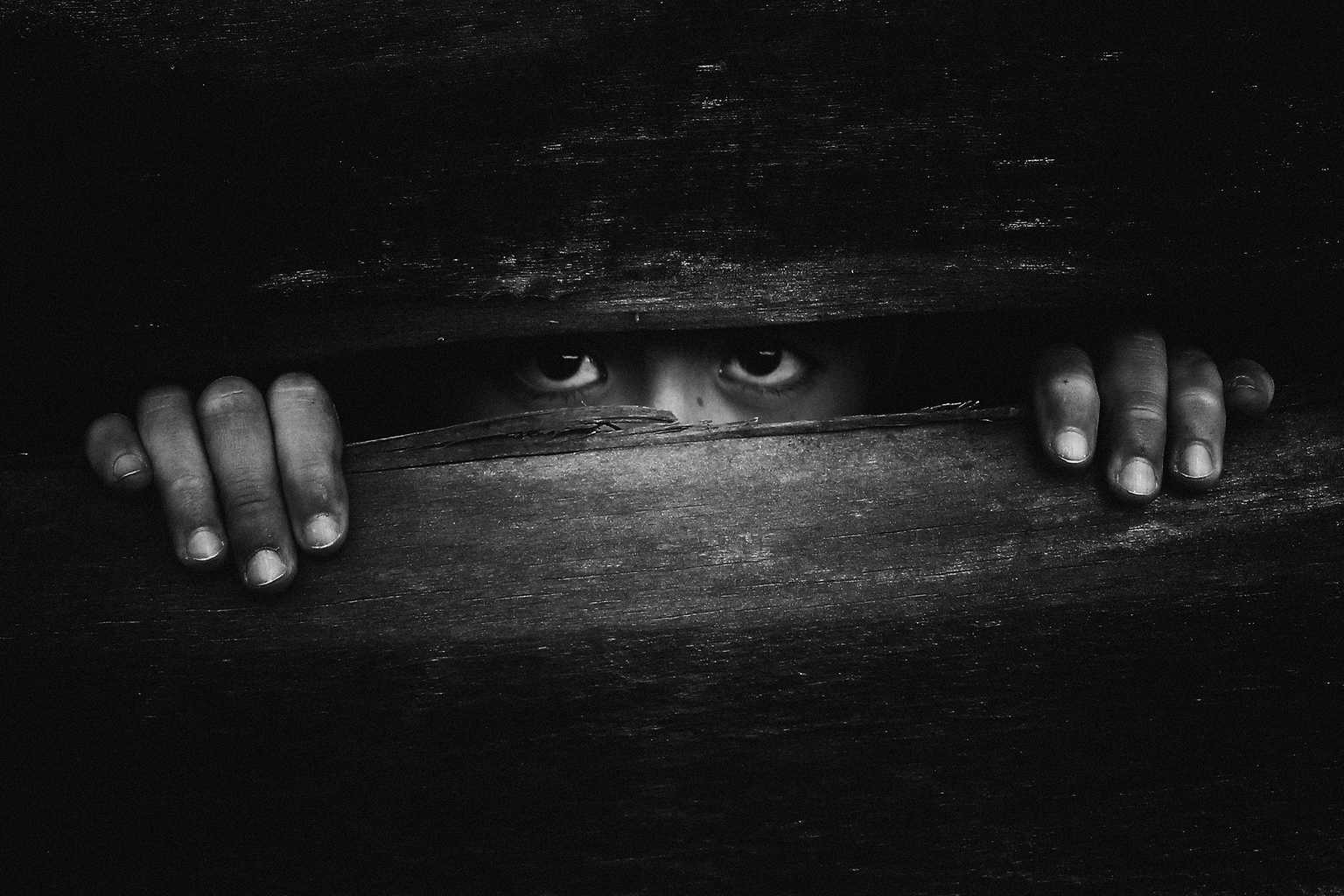

It is the most iconic photograph in Olympic history. But the image of the 1968 Mexico City 200m medal ceremony tells a much deeper story of solidarity and sacrifice.

Not remembered as the greatest 200m final in Olympic memory (that accolade probably goes to Michael Johnson and his world record time of 19.32 at the Atlanta Games or Usain Bolt at 2016 Rio Olympics), this moment would be remembered for the events after the race: three athletes’ protest against the violence, subjugation and oppression of racial injustice.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos were touted to win gold and silver in the 200m for the United States at the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games. Both from San Jose State University, Carlos and Smith were the fastest qualifiers for the 200m final.

Peter Norman (he’s the man without his fist raised in the famous photo) wasn’t expected to reach the final. Yet, he ran 20.00, which still stands as an Australian record for the men’s 200m. He should be celebrated as one of Australia’s greatest athletes. But many Australians know nothing of the athlete nor the person that is Peter Norman. Yet, it is not his athletic prowess that has him etched in history, but his posture and practice of solidarity for that which he cared for most.

The son of Salvation Army Officers from the northern suburbs of Melbourne, Peter Norman grew up in an Australian cultural context similar to that of South African Apartheid. Australia was shaped culturally by a history of white, colonial violence and oppression and a system of legalized white supremacy known as the “White Australia Policy.”

The “White Australia Policy,” as it was known colloquially, was a conglomeration of policies designed to limit access to Australian citizenship to individuals of non-British descent, Indigenous Australians and migrants from countries other than the UK and Ireland. This collection of racialized red tape provided a foundation for the Australian Government to deport any “undesirable” people who had settled in a domestic colony prior to Federation in 1901.

In most sections of Australian society in the early 1960s, the “White Australia Policy” was regarded as a success for white supremacy. It homogenized the population, inhibiting the power, influence and voice of the marginalized and the oppressed—namely the Australian Indigenous community. It was only in 1965 that Australian Aboriginals were granted the vote unilaterally. In 1967, a referendum was held to decide if the constitution should be changed and include the Australian Aboriginal community in the national census. Although the political context was shifting in Australia, in the shadow of the civil rights movement, the racist status quo was as embedded culturally as it was in the United State and South Africa.

As the three athletes prepared for the medal ceremony, Smith and Carlos wanted to use this opportunity to protest issues of systemic injustice in the United States in three distinct ways. First, they chose to receive their medals without shoes, wearing black socks symbolizing the poverty experienced by the African-American community. Next, they decided to do the Black Power salute with gloves, during the national anthem prior to the 200m final. Yet, John Carlos left his black gloves in his room in the Athlete’s Village. It was Peter Norman who suggested that Smith and Carlos share gloves so they could still execute the salute. Finally, both Carlos and Smith wore the “Olympic Project for Human Rights” badge. The purpose of this badge was to protest against racism in sport and racial segregation in the US.

As the athletes prepared to walk onto the field to receive their medals, Peter Norman asked to wear a badge as a demonstration of solidarity. He received his badge from a member of the U.S. rowing team and the three men walked toward the dais, in unity, for a common cause.

Although he may not have raised a fist on the dais, he did lend a hand.

Peter Norman wasn’t daunted by the protest of Smith and Carlos. In fact, he was compelled to participate with his mates. For Norman, it was his faith instilled within him from an early age that cultivated a posture and practice that sort him to use his embodied influence to actively contend for those around him, despite their context, conviction, color or creed. In doing so, by wearing an American human rights badge on his tracksuit during the medal ceremony, he gave his tacit support to those watching.

Norman’s athletic career, along with Smith’s and Carlos’, ended the day he took the dais to receive his silver medal. Smith and Carlos were suspended and sent home to the U.S. immediately. Norman, upon returning home to Australia, was ostracized by the Australian community and shunned by the Australian Olympic Committee. In the lead-up to the 1972 Olympics in Munich, despite producing a time that would have qualified him for the event, Norman was not picked.

While his participation may not seem as overtly outrageous, his act of solidarity etched in history a model for people who embody “whiteness” to engage in practices of public peacemaking against the struggle of systemic racism in their local context. Not many people would do more, for they do not believe that sport and politics should mix—despite the reality that sport in and of itself, like everything, is political.

For many reasons, we love our sporting heroes. They’re icons of excellence who embody ideals that bring us hope, joy or an excuse to disengage from the responsibilities of life. Some of us live vicariously through these icons. But when our sporting heroes use their platform to have a conscience or use their platform to make a moral judgment, we crucify them.

Similar to the actions of the Miami Heat who wore hoodies in 2011 as a means of seeking justice for the killing of Trayvon Martin. Or when NBA and NFL players wore “I Can’t Breathe” T-shirts during their respective pre-game warm-up. Or when Colin Kaepernick and other NFL athletes took a knee during the national anthem in protest of police brutality against people of color.

It is these images and in these moments that it becomes imperative for us all to kneel, raise a fist or wear a badge in solidarity with those who are subjected to realities of oppression and subjugation.

2018 represents the 50th anniversary of an actionable love and image of unity that not only immortalized these Olympic champions, it ended their careers. Yet, they still acted with courage and empathy.

Reggie Williams, Associate Professor of Christian Ethics at McCormick Seminary, stated that empathy is the ability to share in the experience of others—to enter their context and reflect on their concrete needs for justice without losing grasp on one’s own separate identity. This is true in light of Peter Norman’s actions. Without his example and image, we all lose. We, as those who embody “whiteness” and its loaded stereotypes will continue to fail again and again if we miscarry our responsibility to contend for those around us.