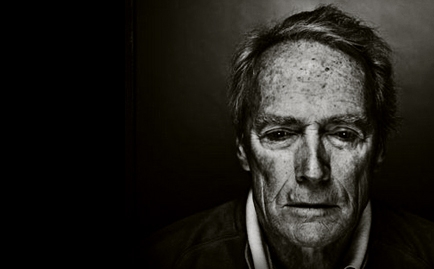

Early in his career, Clint Eastwood established himself as a tough guy with roles like the Man with No Name in Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, and as Harry Callahan in Dirty Harry. But since the early ’90s, Eastwood has focused less on acting and more on directing, crafting films that frequently make a big splash during awards season. More than that, though, he’s created a body of work deeply concerned with the the spiritual questions of the value of human life and the grief that follows in death’s wake.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in 1992’s Unforgiven. Eastwood stars as William Munny, a farmer whose past as a notorious killer catches up to him when a young man calling himself the Schofield Kid asks for help killing two men who cut up a prostitute’s face. Munny is reluctant to leave his home and his young children behind, remarking, “It ain’t easy killin’ a man,” but the lure of a $1,000 bounty pulls him and his old partner Ned Logan (played by Morgan Freeman) out of retirement.

Their journey proves to be more difficult than any of them could have imagined, though. After years spent on a farm, his loving wife by his side, Ned can no longer muster the strength it takes to shoot another man. The Schofield Kid, likewise, is left shaken after witnessing his first death. Tearful and drunk on whiskey he admits he’d never killed a man before and then relinquishes his gun. “I won’t kill nobody no more,” he says, “I ain’t like you, Will.”

Not only do these two moments illustrate the trauma involved in taking another life, they also run contrary to the attitudes of the typical Western, which thrives on a “shoot first, ask questions later” mentality. The larger-than-life archetypes of the genre are replaced with ordinary people who only want to live as peacefully and decently as possible in a world of cruelty.

Eastwood turned another genre on its head in 2004 when he released Million Dollar Baby. For the most part, Baby is a standard sports flick about an amateur boxer named Maggie Fitzgerald who rises to the top thanks to Eastwood’s grizzled Frankie Dunn, a legendary cutman and trainer. The twist comes in the third act, when Maggie is severely injured during a title fight and left paralyzed from the neck down. Maggie, distraught over all that she’s lost, asks Dunn to end her life, and everything that happens from that point on—from the festering ulcers on her body, to her attempted suicide—is intended to justify Dunn’s decision to help her.

The audience is manipulated by all this, too. We are forced to either approve of what Dunn does, or take the supposedly less compassionate view that he acted wrongly. There’s something almost unethical about putting viewers in this position, and it’s part of why the movie is difficult for Christian audiences to accept. Except that, for all its machinations, Eastwood’s movie doesn’t devalue human life, as some would think; rather, it speaks to humanity’s inherent value. Instead of returning to his old life, Dunn disappears. The last we see of him is through the window of a roadside diner where he and Maggie stopped for a slice of homemade pie one night. The implication is that Dunn will remain haunted by his actions for years to come. If the movie’s intent had been to devalue life, it’s doubtful that killing Maggie would have made such a lasting impression on his soul. Instead, taking a human life is depicted as the difficult and devastating thing that it is.

Equally as effective is Eastwood’s 2003 film Mystic River. Sean Penn stars as Jimmy Markum, an ex-con and the owner of a Boston convenience store. His life is upended when he learns his 19-year-old daughter has been murdered. Overcome with grief, he recruits some local thugs to help him track down the killer. The story becomes even more tragic, though, when the trail of evidence leads him to Dave Boyle, a boyhood friend who was molested as a child and has been acting strangely ever since the recent murder. Jimmy takes this as proof that Dave is the one who took his daughter’s life, and he in turn takes Dave’s.

What makes the message of Mystic River doubly powerful is that the audience knows Dave is innocent (of this particular crime at least) and can only watch as his former friend first stabs him and then shoots him at point blank range. There isn’t a more powerful example of how revenge makes monsters of men in all of Eastwood’s films.

There are plenty of examples, though, for how the director develops similar themes in movie after movie. The elegiac tone of Flags of Our Fathers and Letters From Iwo Jima speak to the scars created on the battlefield in service to one’s country, while Gran Torino promotes self-sacrifice over vengeance as Walt Kowalski, the film’s hero, chooses to sacrifice himself to save a troubled youth.

With Hereafter, in theaters today, Eastwood finally had the chance to rip aside the curtain and reveal why humankind has such value. Instead, he does everything possible to brush religion aside. The result is an amorphous version of the afterlife that resembles a cosmic waiting room rather than a paradise ruled by a compassionate God. You could almost think of it as a version of heaven for atheists. But this is unreasonable (to borrow a word from the rationalists). How is it that life can continue after death without the presence of a divine, life-giving entity? It’s a mystery that Hereafter isn’t interested in exploring, and overall, the film casts a slight pall on an otherwise meaningful body of work.

Andrew Welch is a freelance writer from Roanoke, Texas.