Several years ago, in one of D.C.’s largest suburbs in Arlington, Virginia, I came home to the cheerful apartment I shared with two fellow Southern women and I was surprised to see a new book positioned carefully with pride on our coffee table. I sat on the couch, leaned a bit closer and realized I was looking at a biography of Robert E. Lee, the Commander in Chief of the Confederate Army. I instantly recalled the photo one of my roommates had shared on Facebook of her parents dressed in Confederate uniforms for a Halloween party and knew this wasn’t a joke. I knew that a hard conversation, one I’d had before with others, was just around the corner.

Newcomers to Northern Virginia, a progressive region just outside the United States capital, may be surprised to find that one of its major highways is named for the president of the Confederacy—the Jefferson Davis Highway. Visitors may likely have the same jarring feeling I had when my family moved from New Jersey to South Carolina and I saw Confederate flags on backpacks, belt buckles and cell phone cases at my high school while no one batted an eye.

Seeing images of the Confederacy, highways named after Confederate leaders, statues of Confederate generals in places of honor and, finally, a Confederate leader’s biography on my coffee table aroused a variety of emotions, but more than anything, it aroused confusion.

In a country that touts being a melting pot and is known for such a strong sense of patriotism that many international observers consider obnoxious, it is confusing that a place of honor would be given to people who committed the highest form of treason. Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson and others did not fight on behalf of their individual states; they fought on behalf of their self-proclaimed new nation: The Confederate States of America. By the Civil War’s end, 11 states had voted to leave the United States of America and join this Confederacy.

All 11 of these states were slave-holding states and this was certainly no coincidence. While everyone living in the Confederacy was not a slave-owner, the leaders of the Confederacy were not only advocates for the continued legality of the oppressive system of slavery, they were slave-owners themselves. Some may argue that many of the United States’ Founding Fathers were also slave-owners, so what’s the difference? My response is that George Washington fought for America’s independence; Robert E. Lee and other Confederates fought explicitly to restrict that independence from black Americans.

Advocates for Confederate statues and flags often proclaim that these symbols simply represent Southern heritage. However, as a descendant of at least six generations born and raised in South Carolina, I strongly disagree. For almost half of the residents of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, the Carolinas and the other slave-holding states in the Confederacy, being Southern wasn’t the problem; being enslaved was. The Confederacy may have lost the Civil War, but that doesn’t mean the South lost. When the Union won the Civil war, 40 percent of the South’s residents legally earned their freedom. Many would consider that a win.

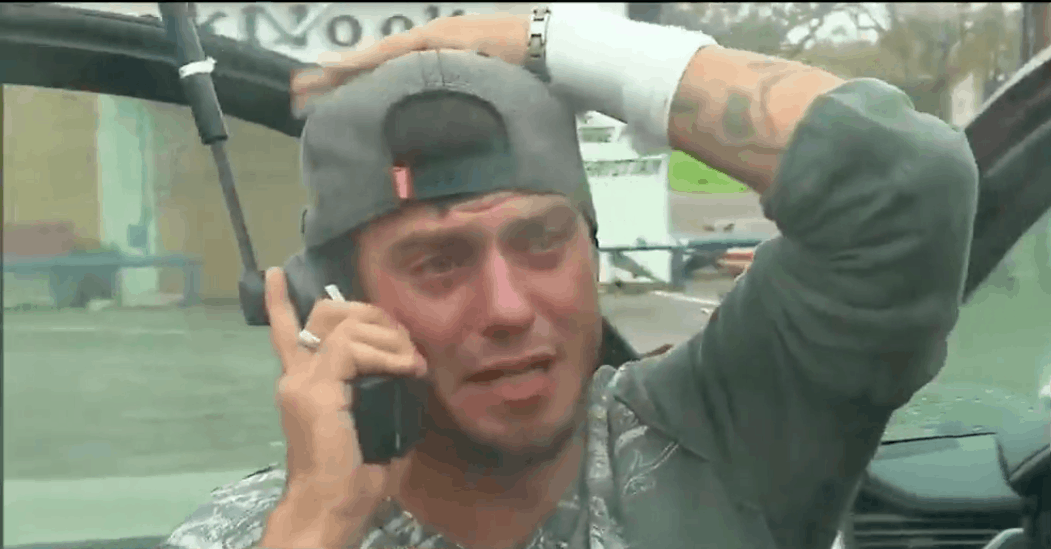

Southern heritage we can all embrace and be proud of is warm hospitality that catches Yankees off-guard. Southern heritage is thick stacks of biscuits served by someone with an even thicker accent. Southern heritage is doing more than surviving when times are tough—it’s thriving with innovations like the cotton gin. It is a willingness to get dirty to get the job done. Today, as Houston suffers with the ravages of Hurricane Harvey, Americans are seeing firsthand, neighbors saving neighbors, risking their own lives—that is the legacy of Southern heritage.

Confederate statues, however, represent the South’s ugly racist past built on an oppressive system that many erroneously believed was morally sound and God-ordained. These beliefs were the foundation for the Confederacy, and unfortunately, they persist today as different strains of the same virus as evidenced by the recent tragedy in Charlottesville. Even if one argues that Confederate statues are meant to honor the South and not slavery, that argument falls flat when we consider that many of the statues throughout the South were erected not in the immediate wake of the Civil War, but decades later as the Klan rose to power to intimidate local citizens of color.

Confederate statues aren’t offensive and disrespectful just to the descendants of the enslaved in this country; they are offensive to all Southern citizens committed to progress in race relations and who stand against hate and for neighborly love for one another. Statues of Confederate leaders that tower over citizens inaccurately suggest that the South’s best days are behind them.

As a proud Southerner and Christian advocate for justice, it is clear to me that the South can rise again, but this century, it can rise as a beacon of racial reconciliation and become a living testimony to a people’s ability to heal from even the most horrifying of wounds. But the South can only do that when it divorces itself from the glory of the Confederacy, and marries the lessons it learned from that treasonous period.

When you remove Confederate statues, you don’t remove history; you forecast the future. Our country’s museums, textbooks, documentaries and memorials continue to provide the context needed to understand the comprehensive perspective of our country’s most dramatic internal struggle to ultimately decide who she would be. It is a misrepresentation of the truth for generations to gaze up at the majestic glory of a Confederate general without the context of the cause he fought for—a cause that included the brutal denial of humanity to his fellow man.

The South, arguably more than any other region in the country has an opportunity to teach the world about how to correctly understand and position the past while pointing towards a brighter future that includes all of the South’s citizens—as equal participants and contributors.

In 1869, when invited to mark the ground of Gettysburg with “enduring memorials of granite,” one retired Civil War veteran declined to attend with a letter that said, “I think it wiser not to keep open the sores of war, but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife.”

Who are we to argue with veterans, particularly when that veteran was none other than Robert E. Lee?

I challenge statue advocates to ask themselves, if Robert E. Lee himself opted out of large, brooding monuments to the people who he fought alongside, what is your motivation to advocate for them? Is it really Southern heritage?