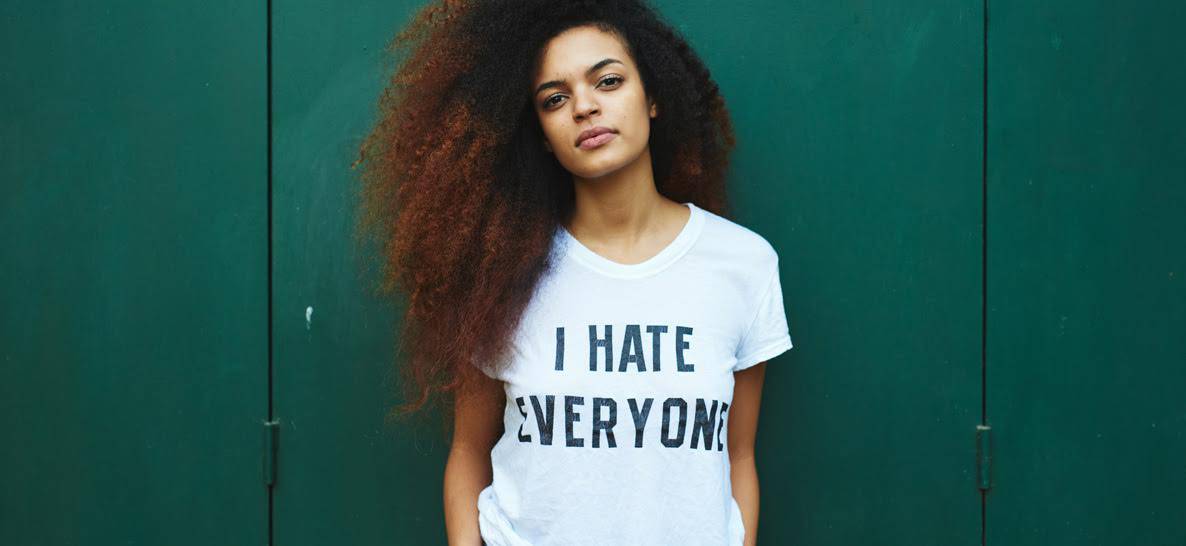

We’re standing at a very particular moment for the Church. We’ve even arrived at the point where much of culture most closely associates Christianity with this one singular trait (at least, according to Google).

Many voices in the American Church have been consumed by an almost singularly identifying trait: Their anger. Even though most Christians aren’t angry people, the loudest voices—and the ones that shape perceptions about the Church—tend to be the ones that are the angriest.

People are upset over laws. They’re upset over things politicians say. The are mad that a gorilla got killed; they are mad that people are mad about the gorilla. They are mad that some pastors are saying things they don’t agree with.

They are mad at the government. Mad at Facebook. Mad at the media. Mad at how other people parent. Mad at what some people see as acceptable forms of entertainment.

Somewhere along the line, many in the Church, have been tricked into acting like anger is the same thing as righteousness.

They let their anger define them.

They’ve been led to believe that by expressing their anger at everything they don’t like (whether it’s warranted to or not), they are separating themselves from sin. They’ve been tricked by a culture of outrage into believing that by separating themselves through their anger, they are more righteous than the people who’ve yet to be consumed by all the rage.

It feels like the more angry they are at things, the more they are above them.

But, if we give into trivial outrage, we are not only hurting ourselves. We might be preventing the change we really want to see.

What Is ‘Righteousness’?

James is arguably one of the most theologically controversial books of the New Testament. Martin Luther was so troubled by its calls for people to pursue righteousness through good works that he wanted the whole book to be thrown “into the stove.”

James is a book about righteousness, because it’s about the need for helping others: “What good is it, my brothers and sisters, if someone claims to have faith but has no deeds? Can such faith save them?” James doesn’t suggest that our actions will save us; but it does say that the saving grace of salvation should spark us to start living in ways that personify the savior who issued that grace.

James 2 gives several examples of “righteousness” that was achieved when people’s actions (in this case, Rahab’s and Abraham’s) aligned with their faith. “You see that a person is considered righteous by what they do and not by faith alone.”

But, before he described what righteousness is, James clearly states what it is not: “My dear brothers and sisters, take note of this: Everyone should be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry, because human anger does not produce the righteousness that God desires.”

The Time to Mend

If we’re honest with ourselves, anger feels good. It’s like being so assured that we are right about something, that we let our certainty and sense of justice consume us.

This isn’t always a bad thing. Some injustice can only be met with a truly righteous sense of anger. James tells followers to be “quick to listen” because there are people and movements whose angry cries for justice must be heard. But if our default reactions to everything in culture we don’t like is anger, than we risk being so consumed with our own outrage, that we drown out the voices that need to be heard—the voices pointing out systematic injustices, violence and corruption.

Thats why anger shouldn’t be our default, especially when it comes to trivial arguments on social media and debates about news stories that don’t even effect us directly. Because, when that happens, we can get so caught up in finding more things to fuel our rage that we stop looking for things that can be redeemed. We only want stuff to condemn.

Ecclesiastes says, “There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under the heavens.” There is “a time to mourn and a time to dance.” There is “a time to keep and a time to throw away” and “a time to be silent and a time to speak.”

And, perhaps most applicable to our current cultural state, “a time to tear and a time to mend.” If we spend all of our time tearing through comment sections and church debates, we never get a chance to mend the thing that’s been damaged.

That action—the one that brings healing, grace, redemption, correction and hope—is the righteousness James is talking about. It’s our responses to anger. It’s recognizing that the time to tear is followed by the time to mend.

The Right Response

James understood that it’s easy to get angry. It’s easy to look at all of the brokenness, all of the hurt, all of the stupidity and all of the hate and just get mad. And, sometimes, getting mad at egregious injustices is the right response.

But, after the easy part, comes the hard part.

We’re called to help redeemed the brokenness. We’re called to bring healing. We’re called to produce a fruit of the spirit that isn’t rage, anger and division, but love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. We’re called to stand beside the disenfranchised with love and understanding and to hear the plight of people who have a reason to be angry. We’re called to know when to be silent and hear their cries and when to speak up to help restore justice.

Though we know that times of tearing will happen, ultimately, we serve a God that’s also interested in mending.

That’s when all of our righteous anger actually becomes synonymous with the righteousness we’re called to produce.