From the time we are young, we develop a narrative that helps us understand who we are, who we are becoming and why we are here, a narrative that we largely adopt from our parents and then develop gradually over time. But perhaps more interesting than what this narrative says is what it avoids saying, what it does not symbolize. While we come to see this story as describing who we are, it often has nothing to say about certain behaviors we engage in. There are behaviors we enact that we treat as taboo—they exist, and yet remain unspoken. This is somewhat analogous to a family who never speaks about an affair that everyone knows took place. It is a reality that has not been given form in the discourse of the family.

In a similar way, there are things we do that clash with the clean, coherent and cohesive story that we have about ourselves. Acts that are patently real and yet not acknowledged as such. By definition, these are very hard to see because they are parts of our personality that have not been brought to the light. In order to find them, we often need others to reflect back what they see in us. These kinds of encounters can be described as “wounds from a friend,” difficult conversations that expose something we would prefer not to acknowledge, yet these confrontations are required if we hope to grow and mature. When confronted with our taboos, we may initially be astounded and then engage in an act of rationalization in which we try to deny the truth of what has been pointed out.

Tabloid talk shows operate with a similar logic. Someone is brought onto the show, perhaps thinking they are there for a reason other than the true one, and then confronted with some problematic behavior. They may have a problem with overeating, aggression or drug abuse. In such situations, the individual might initially be shocked and surprised by the accusations, having never articulated the material reality themselves. Then there is a point where the person considers what is being said but dismisses the accusations (claiming they are false) or defends themselves (claiming the actions were justified and can be explained within the coordinates of their current self-understanding). However, after the initial shock and defense have worn off, the individual might break down and admit that they have a problem, at which point they are often offered professional help by the presenter. Of course, I am not defending such shows; in fact I would be concerned about their effect for attempting to take a number of key moments in the process of human change and make them all happen in a 20-minute slot for entertainment. However, they are useful in seeing how disavowal (not seeing what one sees), defense (trying to justify oneself) and acknowledgment (bringing one’s own behavior before oneself) operate.

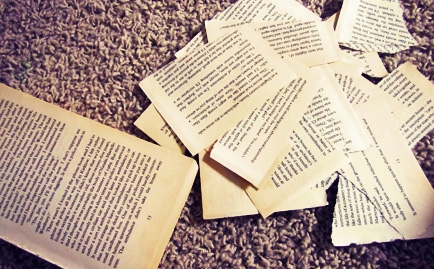

Cutting up the Bible

We can see the same logic at work with the way that many people read the Bible today. For large numbers of churchgoers, it is presented as a clean, coherent and cohesive text, an image we tend to adopt for ourselves. Then, depending upon what we think the message of the text is, we simply refuse to see anything that might contradict our reading. We treat those parts of the text that might contradict our interpretation as taboo. In other words, we see them without acknowledging them; we look at them in the same way a cow gazes at a passing car.

When we are confronted with the broken nature of the text and the way in which we have repressed some parts of it at the expense of others, we can often be shocked. Talking with young Evangelical Christians about the text, I have often found this reaction. They simply never thought it was possible, even though they have read the text a number of times themselves. When the facts are presented, there can often be anxiety and even hostility. They either explicitly avoid looking at the evidence provided or attempt to find ways of integrating the new information with their already existing worldview. Finally, however, there can be a point of recognition that opens up a different way of approaching and engaging with the text.

There have been various attempts by the liberal tradition within Christianity to remove parts of the Bible that they don’t agree with, something that more conservative Christians have vehemently attacked. However, the truth is that they may simply engage in a different, more clandestine, form of deletion, one that doesn’t require physically cutting up the text: they do the cutting internally.

Philosophically speaking, the claim that the Bible in its entirety is literal and inerrant (i.e., self-evident, internally coherent and a reflection of the mind of God) operates as a master signifier. It is a claim without any specific content, worn as a badge to let you know what team you play for. It doesn’t matter too much how you actually fill in this empty container with true content, as long as you make the claim. It functions as a shibboleth, identifying you as being in a certain tribe.

But as soon as one attempts to enact what it might mean to hold the Bible as literal and inerrant (i.e., to fill this claim with content), one must treat large parts of the text as taboo. The person who makes the abstract claim that the Bible is literal and inerrant, when enacting the claim, always refutes themselves.

Peter Rollins is a widely sought after writer, lecturer, storyteller, public speaker and the author of Insurrection (Howard 2011). This article is republished from his blog with permission.