The 20th-century journalist and Christian apologist G. K. Chesterton once said, “There are two ways of getting home; and one of them is to stay there. The other is to walk round the whole world till we come back to the same place.”

Chesterton’s point was that truth might be closer than you realize, perhaps right under your nose. And sometimes, like with the prodigal son, truth is found at the end of a long road back to the Father’s house.

Chesterton was speaking specifically about Christianity. In his book The Everlasting Man he contrasts two ways of analyzing the Christian faith. The first is from the inside. The second is from a million miles away. As he writes, “The best relation to our spiritual home is to be near enough to love it. But the next best is to be far enough away not to hate it.”

In other words, sometimes stepping just outside the front door of a particular view (like Christianity) leaves you too close to have a clear perspective. You can be standing beneath the awning while complaining about the shade. Your proximity itself creates emotional and intellectual blind spots.

As Chesterton puts it, “The popular critics of Christianity are not really outside of it … Their criticism has taken on a curious tone; as of a random and illiterate heckling.” You likely know what he was talking about: Many of the complaints and criticisms we hear about Christianity are more emotionally charged than carefully reasoned. And safe passage to meaningful conversations with each other can be hard to find.

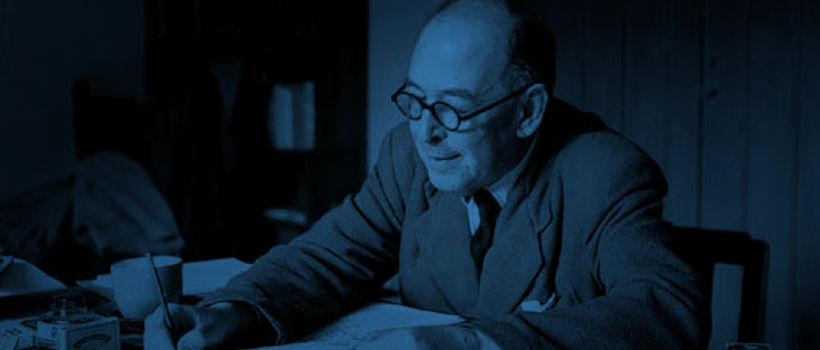

Lewis Leaves Home

This is well illustrated in the life of C.S. Lewis. As a young man, Lewis navigated this same terrain. He describes this journey in his first published work after his conversion to Christianity, The Pilgrim’s Regress. It’s a fictional account of his conversion that he wrote over a holiday visit with his childhood best friend. Of course, Lewis patterned the work after John Bunyan’s classic The Pilgrim’s Progress.

Like Bunyan, Lewis uses allegory to make his points. But his “regress” offers a glaring contrast to Bunyan’s “progress.” Lewis wanted to illustrate that his character found spiritual fulfillment not by progressing to a far-off land to be freed from a heavy burden—but in the fulfillment of a longing that could take place only in the Christianity he previously rejected.

Lewis made spiritual progress by turning around and retracing his steps. Sometimes, this is exactly what progress looks like: Turning around and heading back the other way. Think about it, we can hardly call going further down the wrong road progress.

Lewis later described this in his autobiographical work Surprised by Joy: “But then the key to my books is Donne’s maxim, ‘The heresies that men leave are hated most.’ The things I assert most vigorously are those that I resisted long and accepted late.”

As a young man Lewis walked away from his spiritual upbringing. And it took some time for him to get far enough away to stop hating it. But then he came back, close enough to learn to love it. He walked around an entire world just to come back home.

And, his tour guide was none other than Chesterton.

Finding a Guide

Chesterton’s book The Everlasting Man was a response to H.G. Wells, whose book The Outline of History sold more than two million copies and has been translated into multiple languages. Wells describes his massive tome as “an attempt to tell, truly and clearly, in one continuous narrative, the whole story of life and mankind so far as it is known to-day [sic].” Wells brought his skill as a wordsmith and his philosophically nuanced skepticism fully to bear on the project.

The influence of The Outline of History and of the Wellsian view is difficult to understate. In one fascinating instance, a young Jewish father in New York City required his eight-year-old daughter—who was herself an intellectual prodigy—to read Wells in its entirety. As a result, she dropped the faith of her family and became an atheist.

But the book was not without its challengers. Just a couple of years later, back in Britain, the opinionated British journalist, Chesterton, took up the task of countering Wells’s manifesto. Chesterton challenged Wells’s premise that atheism offers a more compelling account of history. And he contended that Wells’s main problem in the book was simply that he was wrong.

Coming Home

The then-atheist professor Lewis read The Everlasting Man in the mid-1920s and later described the book as a major contribution to his journey away from atheism and his conversion to theism. In the following years, Lewis moved from theism into the thing itself, the gospel of Jesus Christ.

And remember the young girl in the Bronx? Lewis’s keen mind and clear prose providentially reached that same household where Wells’s spurred her into atheism. Now a grown woman, she was jolted by Lewis’s presentation of the Gospel. She went on to reject atheism, like Lewis years earlier, and embraced the Gospel message he wrote about.

Her name was Helen Davidman. At least until she moved to England and subsequently became the wife of Lewis.

Some people might leave the faith of their childhood. But Christians can take heart: Like the prodigal son, they may find that the far off country isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be. And even if they have to cross the entire world, maybe, one day, they will find their way back home.