We all love the Psalms. They’re a beautiful, poetic expression of everything from praise to pain to joy.

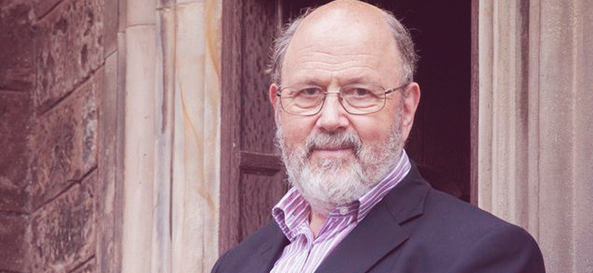

But sometimes, we can dismiss the Psalms as only beautiful poetry, forgetting that they are meant to be prayed, sung and studied, not just glanced through. In his book The Case for the Psalms, leading new testament scholar N.T. Wright examines how the Psalms are more complex and important than we think. We sat down with him to talk about what the Psalms mean to him, our slant on the Bible and the importance of daily devotional time.

Q: Why make the case for Psalms?

A: Well, it surprises me that one need make a case for the Psalms, but in a great many contemporary churches, something very odd has happened, which is that many of the newer churches write their own worship songs—which is wonderful. I’m all in favor of people writing their own worship songs in every possible idiom—but they often simply forget the Psalms. You can go to many churches where if you attend week after week after week you will never ever sing or read the Psalms.

There’s something very peculiar about that because in pretty well every branch of the Christian tradition for 2,000 years, the Psalms have been the backbone of Christian worship. Certainly in all traditional denominations, but in many non-traditional ones, as well, it’s assumed that the Psalms are the heart of worship.

One of the staplines that the publisher has been using is “what would Jesus sing?” which I really like, because the Psalms were the prayer book that Jesus Himself used, and we can see in the Gospels and in the New Testament how Jesus and the early Christians used them, and it seems to me extraordinary that we would ignore that resource in our own worship.

Q: This book feels really personal. What have these Psalms meant personally to you as you continue to read them and pray them and walk through them?

A: I have sung [the Psalms] so often, I’ve prayed them so often, I read them so often, that it’s kind of layer upon layer upon layer of memory and imagination, out of which particular moments emerge when a particular Psalm has suddenly caught me and has meant a sense of God’s new direction or a sense of warning or a sense of encouragement.

And I look back on—how old am I now? nearly 65, and I suppose I started singing them when I was, I don’t know, 5, 6, 7 in church. It’s impossible to say “oh, well this Psalm means this to me and that Psalm means that to me” because each of them now has all these layers of memory.

Q: How do we remove our own Western worldview from our reading of the Bible and yet at the same time have the Bible influence our worldview?

A: It’s not exactly a matter of removing one entirely and doing something 100 percent different, because the reason why all the great worldviews are great worldviews is that they all contain elements of true insight. So it’s a matter of adjusting or subverting or transforming rather than simply throw away everything you’ve ever known and get something totally different.

I mean, to put it over-simplistically, today’s basic Western worldview is still as it’s been for the last 250 years or so—a variant of the old philosophy called Epicureanism, where if there is a God or if there are gods, they’re a long way away; they don’t interfere with us. And the Biblical worldview … says “no, actually God’s domain and our domain interact and interlock and mesh and blend and bounce off each other in a whole variety of ways. And that’s why life is often so confusing and exciting.” And so it’s not a matter of saying that everything you’ve known is completely wrong, because it’s still true that God is transcendent and God is other and God is different.

But, you know, this is complicated and many people find it confusing, but that’s because any time you start jiggling around with people’s worldviews they feel a bit sort of mentally or emotionally sea sick. But this is why the Psalms are so important—they will help us gain stability in that process and help us to inhabit a truer and biblical worldview which will transform the one we’ve all grown up with.

Q: So many believers run from having a devotional life, and I wonder why. Can you share a little bit about why you think there’s such a push back to having a consistent discipline of reading and how we can take next steps against that?

A: Some people quite like establishing habits of life, and other people feel imprisoned by that. That’s a personality thing. I quite like having some settled routines. And actually, I think even those who say they feel imprisoned by having habits of life nevertheless they always make a cup of coffee at the same time each morning or that sort of thing. So people do have rituals that they go through.

I suppose for me, somebody suggested or urged me when I was about 12 years old that it would be a good thing to read the Bible everyday. I started doing so and I’ve never seen any reason to stop. But at the same time, it’s like anything, it’s like practicing the piano—if you’re actually going to make any progress, you’ve got to be pretty regular. And obviously if you’re sick or traveling or whatever you may miss the odd day or two here and there. It’s not a sort of rule that the sky’s going to fall in if you miss the odd day. It’s that sustained discipline, whether short or long.

Part of the problem in our culture today is that people don’t like working at anything. That’s why relationships are so difficult. People think either it’s perfect or it’s rubbish, so as soon as it stops being perfect “oh, it must be rubbish,” so we throw it away. Most things that are worthwhile in human life, you actually have to work at them and only then does the real fruit come.