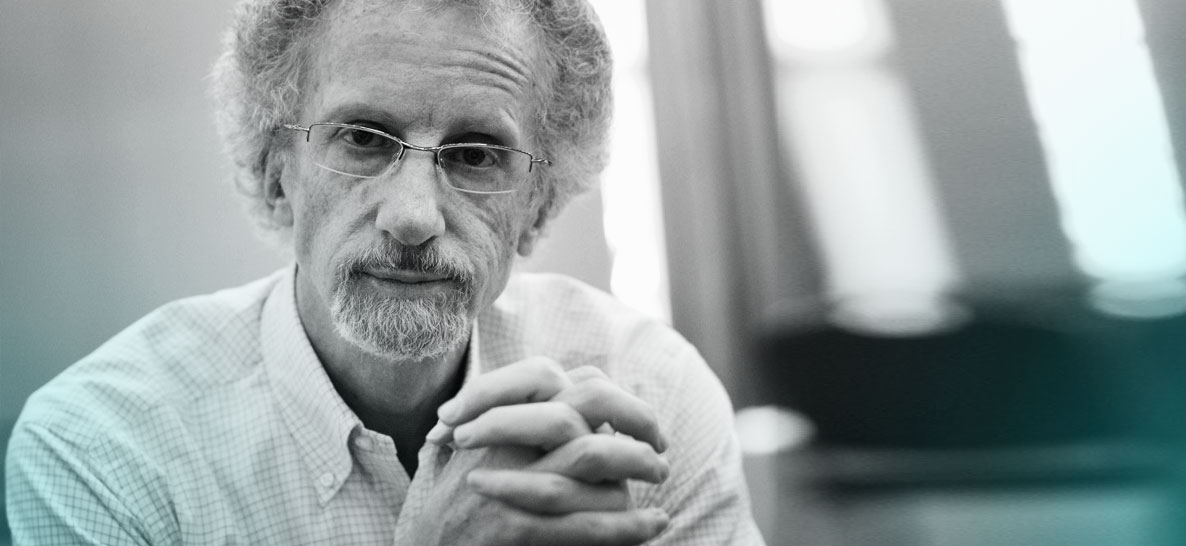

Philip Yancey’s book What’s So Amazing About Grace? has been a modern classic in Christian reading for more than 15 years. In it, Yancey explored what grace in action truly looks like.

This fall, the best-selling author released Vanishing Grace, in which he argues that the American church has often failed at communicating grace and shows how we can get back on track.

We talked to Yancey about his new book Christians in politics and what it looks like to live in grace in a “post-Christian” society.

The title of your new book, Vanishing Grace: What Ever Happened to the Good News? feels like a counterpoint to What’s So Amazing About Grace? Has something changed or shifted in your thinking or perception of grace?

God’s grace is not vanishing, obviously, but we in the Church evidently aren’t doing a very good job dispensing grace.

As I was writing What’s So Amazing About Grace?, I was concerned about the rise of the religious right, the moral majority—not because of the politics, but because a lot of people think that’s the way to make America a Christian country again, whatever that means. And I just didn’t see that as a mission described in the Bible.

I ended up taking much of the material I had developed on that issue—how Christians relate to the wider society—out of that book. Then, I came across a statistic from the Barna group that just jumped out at me. It said in 1996, 85 percent of those with no religious affiliation still had a favorable opinion of Christians. However, by 2010, only 16 percent had a favorable impression of Christians. We weren’t doing a good job at communicating grace.

Do you think there is something unique happening in our time that has not happened before?

A lot has happened. When you interview non-Christians and just ask them, “Tell me about Christians,” they use words like judgmental, self-righteous, hypocritical and then a lot of ‘anti’ words: “They’re anti-science, they’re anti-gay, they’re anti-abortion, they’re probably anti-sex.”

Christians have gotten the reputation of being the moral police in society. Jesus was accused of hanging around the sinners: the prostitutes, the tax collectors. He was accused of hanging out with the wrong crowd all the time. Somehow we’re turning off the “wrong crowd,” whereas Jesus attracted them. Somehow we’re not communicating that we indeed do have some living water that meets a thirst that may go unrecognized, but it is absolutely there among the people around us.

How do we pull ourselves away from those negative labels of Christianity?

I identify three types of people who are especially effective in dispensing grace to an increasingly post-Christian world: activists, artists and pilgrims.

Activists, those are the people who reach out with acts of mercy. It touches people’s hearts. And then they’re open to the message. I can travel to places and I can see the long-term effect of Christians who never talk about their faith, yet they’re reaching out with acts of mercy. They’re affecting people’s hearts, and eventually those people want to know, “Why are you doing this?”

Artists are also effective. Art sneaks in at a subconscious level. The Church historically was the great patron of the arts, and now, some churches are, some churches aren’t. Artists are hard to control, and yet, they are effective in communicating the Gospel to a society that is resistant to it.

And the last phrase I use is pilgrims. We can say, “Look, we’re just traveling along the same road you do, but we know something about the destination, and this is how it has helped our lives,” instead of, “We’re on the inside, you’re on the outside. You’re no good. You’re going to hell.”

If you look at Jesus’ stories, He talks about lost people, lost coins, lost sheep, the lost son. I’ve started looking at people as lost. There are many people who are just wandering around, not knowing why they’re here, how to live, what decisions they should make. And as pilgrims on the same road, we can say, “Here are some clues we’ve learned that may help.”

We just finished an election and we are coming up on another one. Even within Christian circles, this season in politics is divisive. What are some of the specifics, negative and positive, of Christians engaging in political discourse?

We have the luxury of having a voice in our democracy, and that is something we should take seriously. Some Christians are called to be the ones who write the laws, who lobby on causes they believe in. Some are called to be elected.

But there is a great danger, because politics is an adversary sport and every election shows that. Jesus told us, “Love your enemies. Pray for those who persecute you.”

That’s not how politics work. Politics is the world of un-grace where when somebody hits you, you hit them back. When somebody slanders them, you slander them back. So it takes a special kind of person to jump into that arena and be able to hold their Christian character.

As Christians, how do we walk that line of being culturally relevant while also staying true to who God has called us to be?

The phrase Jesus used, of course, is, “to be in the world, but not of the world.” I recently heard Amy Sherman say that Christians tend to relate to society in one of three ways: fortification, accommodation and domination. Fortification—some of us hunker down. We draw the moat. We hang around people like us all day. But Jesus said, “I send you out like sheep among wolves,” not hiding you in the barn in safety.

Accommodation—watering down the message. Jesus certainly never did that. Or domination—the “let’s get our country back” mentality. What it tends to do is alienate people, turn them off. My approach is for us to become pioneer settlements of the Kingdom of God and show the world a different way to be human. We’re not called to clean up society. Jesus and Paul spent no time on that. We’re not going to convert everybody in the world. That would be nice, but it’s not going to happen.

I found this verse in Hebrews 12:15. It says, “See to it that no one misses the grace of God.” If we went through life seeing to it that no one misses the grace of God, we would stand out. We would show the world a better way to be human.