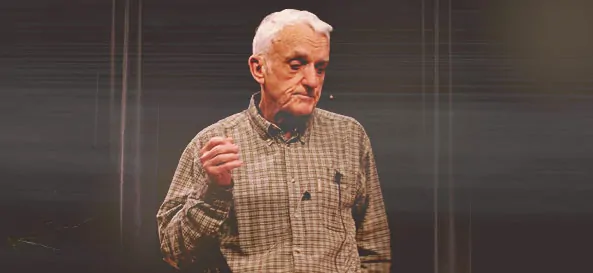

For many Christians, Brennan Manning and grace are synonymous. Therein lies the scandal, and the triumph.

Let’s start with the scandal. Richard Francis Xavier “Brennan” Manning was an alcoholic and an addict. He hurt those close to him by compulsive lying, mainly due to hide his drinking, or if not, as he put it, to “stay in practice.” He was a former Franciscan priest, who broke his vows to marry. He later divorced.

But then there’s the triumph. Manning was a powerful writer and speaker, beloved and respected for his passionate witness to the expansiveness of God’s mercy and forgiveness, the availability of intimacy and communion with “Abba, Father,” and the inexhaustible grace of Jesus Christ. And he would know.

Friday morning, April 12, at the age of 79, he went home to be with his Abba.

But his legacy lives on. Manning published 15 books. He spoke to countless audiences. Many pastors and church leaders have credited Manning with sustaining their spiritual journey through the message of the “reckless, raging fury that they call the love of God.” Donald Miller recently wrote that Manning inspired writers, artists, filmmakers and musicians by convincing them “of the safety of grace.”

Michael W. Smith, for example, admits that he’s given away so many copies of The Ragamuffin Gospel over the years that he’s lost count. Rich Mullins, who died an untimely death, was so moved by Manning’s life and writings that he named his musical group The Ragamuffin Band. Mullins said hearing his teaching on the true nature of grace “broke the power of mere ‘moralistic religiosity’ in [his] life, and revived a deeper acceptance that had long ago withered in [him].”

Prior to Manning’s death, Philip Yancey wrote these admiring words in the foreword to Manning’s memoir, All is Grace: “I have watched this leprechaun of an Irish-Catholic hold spellbound an audience of thousands by telling in a new and personal way the story that all of us want to hear: that the Maker of all things loves and forgives us.”

Sure, it’s a simple concept. But Manning lived it as if grace were his only lifeline—and it was.

Like these and many more, I am also a beneficiary of Manning’s legacy. In 1995, dc Talk’s album Jesus Freak featured a quote from Manning. The track “What if I Stumble?” opens with a crackly voiceover: “The greatest single cause of atheism in the world today is Christians, who acknowledge Jesus with their lips, then walk out the door, and deny Him by their lifestyle. That is what an unbelieving world simply finds unbelievable.”

Until this week, I had no idea who had spoken those words. But as a teenager, this truth shifted entirely the way I was following Jesus. It gave me the confidence to believe Christ could take my life, simple and small as it was, and make it profound, living evidence of His work in the world. And hopefully, one that an unbelieving world might trace back to the source in Jesus Himself.

Manning’s life was just such a profound mystery. His legacy is vast, though difficult to trace. For those who encountered him through audio recordings, the written word, or in person, Manning’s influence was pervasive in often an intangible way.

More elusive and difficult to follow are the “Kingdom tremors” pulsing outward from his life; ground zero for the explosive power of the scandalous message of grace that possessed Manning’s heart, then rippled outward. Manning wrote, “I have been seized by the power of a great affection.” And that affection left a wake.

Perhaps the responses to his death have shown just how expansive that wake really is. Tributes and testimonies of Manning’s outrageous legacy of grace continue to pour in.

I believe two themes in his influence are worthy of note. First, Manning is consistently credited for helping people to understand “the Gospel of grace and the reality of salvation.” Second, Manning’s insistence that “Jesus hung out with ragamuffins,” of which he was one, gave his message an appealing texture, one his hearers could identify and comprehend. We can’t always see ourselves in books about leaders, world-changers, radical disciples. But we can certainly see ourselves like Manning—a ragamuffin.

We can see ourselves in he who was a drunk and a liar, a divorcee and an ex-priest who broke his vows to the Church.

Our sins may differ. But Manning acknowledged something we often do not. In The Ragamuffin Gospel, he writes, “Though it is true that the church must always dissociate itself from sin, it can never have any excuse for keeping any sinner at a distance.” According to Manning, remaining “self-righteously aloof from failures, irreligious and immoral people” leads to separation from God’s kingdom, but if the Church “is constantly aware of its guilt and sin, it can live in joyous awareness of forgiveness.”

Those who identify with Manning relate to him precisely at the point he admits consciousness of his own brokenness, his own sin, and names his failings. Doing so gives others permission to do the same, to stop pretending, to come face to face with mercy.

Manning says it best himself:

Here is revelation bright as the evening star: Jesus comes for sinners, for those as outcast as tax collectors and for those caught up in squalid choices and failed dreams. He comes for corporate executives, street people, superstars, farmers, hookers, addicts, IRS agents, AIDS victims, and even used car salesmen. Jesus not only talks with these people but dines with them–fully aware that His table fellowship with sinners will raise the eyebrows of religious bureaucrats who hold up the robes and insignia of their authority to justify their condemnation of the truth and their rejection of the gospel of grace.

That Gospel is for me.

That Gospel is for you.

Therein lies the scandal, and the triumph.