Scroll through Twitter or Instagram feeds, and odds are you’ll see Christians of the millennial variety posting quotes from or about Richard Rohr. You’re just as likely to see a faith leader or celebrity talking about him.

Rohr’s influence is wide already, and it’s expanding. Some 30 years ago, Rohr founded the Center for Action and Contemplation. Today, he trains people from all kinds of backgrounds and traditions—Rohr explains that of these students “a third of them are evangelical, a third are mainline Protestant, several are unbelievers and the rest are Catholic”—in his unique brand of spirituality and prayer.

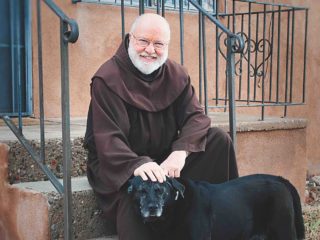

He’s a widely read author and an increasingly popular conference speaker. But he’s not about pop-faith. Rohr is a man of deep tradition—he’s a friar within the Franciscan tradition of the Roman Catholic Church. And since the 1970s, he’s written and taught about prayer and mystic spirituality. He’s popular in some circles and controversial in others (on a spectrum from left to right, Rohr happily sits on the far left).

We sat down with Rohr to learn about the vision of prayer that is creating all this buzz.

You are a Franciscan friar—Can you explain what that means?

Francis of Assisi lived in the 13th century and his big attempt to reform the church at that point was for us to get more identified with the poor. Instead of the clergy being those who are seeking a career or class position, he wanted to aim us in the exact opposite direction.

So in our 800-year history, we’ve been much more identified with those on the bottom. That’s our spirituality.

And “friar” was a term that became popular under St. Francis in order to disassociate ourselves with the monastic orders (who you would call “monks”).

What is your relationship to the Roman Catholic Church?

We’ve always been accepted, ironically, as a minority position within the church. We were never considered heretics or kicked out. To be perfectly honest, I think the church always needed us because we were always more popular with the ordinary people.

What makes you a minority group?

Identifying with minorities. We weren’t trying to be bishops or be in positions of power. That’s why it was so extraordinary when Pope Francis took the name “Francis.” You almost have to be an insider to the Catholic Church to realize what a shock that was. Because for a Catholic, Francis is a non-establishment saint.

That’s the big thing: the realignment with the powerless instead of the powerful and that often put us at odds with the hierarchy.

How would you describe your differences with Protestant Christians?

In terms of humanity’s relation to God, [Protestants teach] some kind of necessary transaction of blood sacrifice that was needed by God to forgive or to love or to accept humanity. The Franciscan school never accepted that. Our Christology is much more of a nonviolent theory of atonement.

To put it in two sentences: Jesus did not come to change the mind of God about humanity, it didn’t need changing. Jesus came to change the mind of humanity about God.

Practically speaking, what does the Franciscan experience look like?

If you would have come to church this morning, I would have been dressed up in all the usual robes. Now maybe the preaching I did would have had a little different character to it, but I celebrate a parish Mass like any other priest would. I hope it’s not in a ritualistic, legalistic or triumphalistic style.

We teach contemplative prayer at the center. Our whole practice is: We come in silence, we sit together in silence for 20 minutes and we train people what to do with their minds during that silence. So our personal style is very different than the parish style.

As you referenced, a huge part of your teaching centers around contemplation and contemplative prayer. Can you explain what you mean by “contemplation”?

Contemplative prayer is largely a practice of disidentification with your own compulsive thoughts and obsessive feelings. I always say when I teach contemplation, “Most people do not see things as they are; most people see things as they are.” They see it through their own agendas, and it doesn’t lead to very broad seeing.

In religious language, we’re handing over to God all the negative, fearful, angry thoughts that try to grab hold of us. Now, when that stream of consciousness clears out—and it does with some regularity—it’s always a wonderful sense of openness to the divine, to whatever God wants to say. Because, basically, you’re not in the way.

To what extent are those who are practicing contemplative prayer hearing from God in your view? Is it literal?

No, quite the opposite. I’d say what characterizes God speaking is very often a sense of gratuity, a sense of vitality. It’s not dogmatic words. Probably the word that would cover most bases is it’s a descendance of presence. So it’s not that you come out of prayer with a big message, but I hope after years of practice you do speak with a greater clarity, compassion, freedom and grace. It’s cumulative in terms of how you hear God and it’s always a sense of gratuity.

Where your wounds and hurt really lie is in the unconscious, and that’s where contemplative prayer goes. It’s the divine therapy, I’m convinced.

The name of your organization—The Center for Action and Contemplation—combines contemplation with, of all things, action. That seems contradictory.

They really are the classic polarity in the history of spirituality, and the pendulum is always swinging to one side or the other. I deliberately put the word “action” first because I don’t think you have much to contemplate until you’ve been out on the field and made some mistakes and loved and sinned and did it wrong a few times.

They really aren’t contradictory; they’re complementary. If you send people into active ministry without any inner life, they’re usually going to become ideologues or rigid. But if you send people into all kinds of inner prayer experiences and they never serve the poor or serve the world, then you’ve got another set of problems.

Is the goal to strike a balance between the two of them?

A balance that converts you. When you face your own shadow, you have to look at your own biases and limitations. But then hopefully whatever wholeness you’ve achieved you’re able to bring it into your ministry and represent it in the world. You’re also calling people on one side or the other to some kind of balance between contemplation and action.

‘Converts’ as in salvation? What are the requirements for someone to become a Christian in your view?

First of all, let me tell you what is not.

I do not think that the New Testament is talking about Jesus taking people to Heaven. This is so corrupt, the whole notion of the freedom, enlightenment and eternal life—I’m not denying eternal life. By pushing this whole thing into the future and making salvation a reward-punishment system where a few win and most lose, I think that’s destroyed the transformative power of the Gospel.

So for me, salvation is a present experience of living in loving union with God and your neighbor and the freedom to love God and the freedom to love your neighbor—which is a lot of surrendering of your own agenda and anger and things that we’ve been talking about.

You’ve written a lot about mysticism and the ‘deeper self’—you talk about the ‘true self’ and the ‘false self.’ what is your deeper self?

Your true self is who you are in God from all eternity. As Ephesians would say “chosen in Christ from before the world began.” Your true self has nothing to do with your temperament, Myers-Briggs type, nationality, race or religious denomination—those are all your false self.

Now when I use “false” I’m not saying it’s bad. I’m simply saying that it’s window dressing. The phrase I use often is from Colossians where Paul says, “We are hidden with Christ in God.” That’s your true self, and that doesn’t go up and down. You can’t lose or gain it. All you can do is allow it, rest in it and draw from it.

The one, always-valid function of religion is to awaken people to their true selves. That’s our job, and what we do so much is simply stir the false self: Try to make the person more Catholic or more evangelical or more law-abiding.

That naked, foundational identity is what you come to rest in the longer you can live in contemplative prayer—you let go of all these passing identities and learn to rest in the one that never dies.