Gus and Bertie set off on a semi-obligatory first date in a well-dented Toyota Prius. They’re both “nice” people who agreed to go out based on a mutual friend’s suggestion because of mutual “niceness.”

A car ride later, the two meet in Santa Monica’s low-lit Buffalo Club Restaurant, a spot pointedly more middle-aged than they. Their conversation attempts center around the other guests, passively cynical takes on whatever—but the awkward, prolonged moments of head-nodding silence communicate far more than their words.

By the end, they each spend more time staring at iPhone screens than at each other, tactics ostensibly to avoid awkwardness, which inevitably feed it.

Bertie just doesn’t want to be there at all and Gus wants to be there with their mutual friend who set up the date, Mickey.

These cringe-worthy moments continue for nearly the entire fifth episode of the quirky, raunchy and acclaimed Netflix series Love.

Gus and Bertie’s date serves as a microcosm for the series—which itself represents a microcosm of modern dating, romance and, yes, love. The show dwells on the awkward and difficult aspects of relationships—which may have less to do with entertainment and more to do with a shared generational experience.

***

Despite a propensity to binge-watch shows like Love, 25 percent of the show’s target audience will actually never get married.

Consider this: A large-scale 2014 study by Pew Research shows that in 1960, about 12 percent of adults ages 25 to 34 never married. By 1980, when the same group was in its mid-40s to -50s, only 5 percent still were single (and not married in between). Research says those numbers are the historical pattern.

But that all changed with this generation.

Each new research group since 1960 steadily increased in its share of never-marrieds. Researchers project that by 2030, the percentage of those never married in this cohort (ages 25 to 34 in 2010) will be 25 percent. More recent research from Pew’s Stateline project in 2016 confirms the trend.

Millennials will be history’s most never-married generation.

Looking at this data, an easy assumption is that, sure, this generation might not be as interested in the institution of marriage, per se, but functional marriage—a committed, sexual, live-in relationship between two people—is taking the place of vow-exchanging, “legal” marriage.

But this assumption doesn’t quite hold up. Millennials express as much interest in marriage as any previous generation, they just increasingly avoid taking the plunge. Their problem is not with marriage. It’s with finding love.

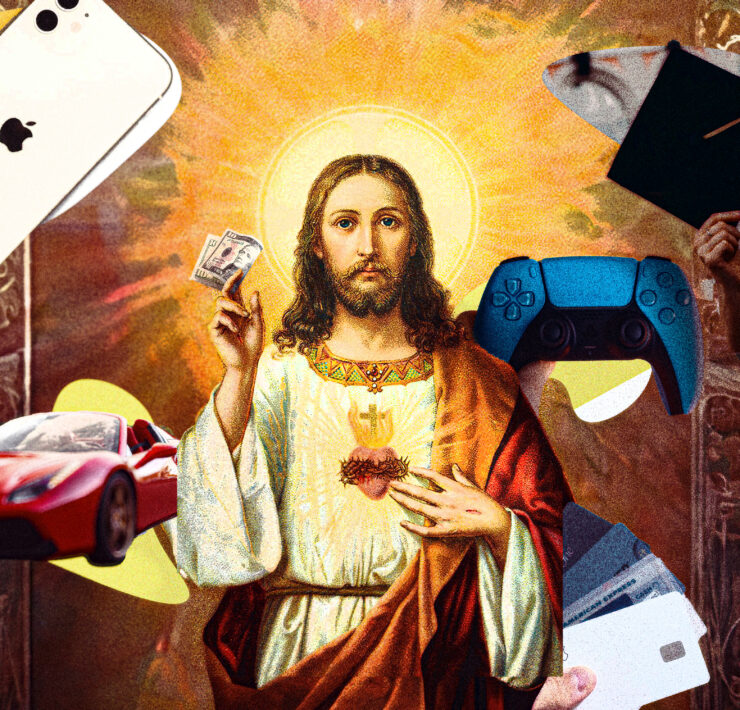

This forms the baseline of Love: Why are people otherwise interested in a loving relationship pushing it off?

***

“The general feeling of, ‘Oh, I’m starting to realize I like this person and I hope they like me back’ is as old as time itself—that’s the thing that we always have on our side with the show,” says Paul Rust, the co-creator and leading man in Love. “The gist of the show is two people are trying to make it work because they like each other.”

Love’s premise is classic: Mickey is the untamable, attractive wild girl and Gus is the nerdy, lovable guy who’s had his altruistic vision of love broken by a failed long-term relationship. But those tropes don’t stay on their tracks, and Gus and Mickey’s “unlikely” romance doesn’t end up pairing a perfectly complementary couple.

Rust thinks Love honestly depicts 21st-century love.

“A lot of times, conflict comes out of how a person gets in the way of themselves,” he says. “All we were trying to do was something that felt truthful, so people having that reaction [that the show’s scenes constantly evoke cringes] it made me think, ‘I guess daily life is just filled with constant awkwardness.’”

***

Marriage in America’s evolving romantic landscape is also the focus of a new book by Rebecca Traister, a writer-at-large for New York Magazine. In All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation, Traister looks at American history and explores how marriage patterns have been key to “big social movements.”

Traister thinks the basic reason people push off marriage is relatively simple: They don’t need it anymore.

“We have to understand that for a long time, marriage was an imperative in one way or another,” she says. “It was how you could have a socially sanctioned sex life, it was how you could have a socially sanctioned family if you wanted to have kids.”

Then the big social and civil movements of the 1960s and 1970s, Traister argues, led to more women in previously barred areas of the workforce and public life. Simply, “there were other things for women to do with their lives besides necessarily attach themselves to a man at the beginning of adulthood.”

And even as these movements suggest progress, a persistent factor in prolonged singleness is a regressive economy—even in religious circles.

For her book, Traister talked with a Christian woman about the “practical economic considerations” of marriage and singleness. This women was committed to abstinence and struggled with being in a romantic relationship. Still, her father demanded that she not drop out of college to get married (like her mother did) because she needed a degree “to preserve [her] economic viability” later in life.

“The pressures are different in communities where there’s still an association between marriage and socially sanctioned adult life, especially for women,” Traister says. “But that pressure isn’t so great as to overcome very real changes in economic expectations for women and how they live their adult lives.”

***

Traister wants to be clear: She contends the trend toward single adulthood isn’t about rejecting love, as much as marriage itself.

“If we were to assume that 25 percent of millennials will never marry, that’s very different from assuming that they will never have committed partnership,” she says. “Most of them probably will in one form or another.”

She’s talking, more or less, about sex.

A 2009 study conducted by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy found that 88 percent of the general population of unmarried “young adults” (18 to 29 at the time) have had sex. And 72 percent of millennials responded to a Barna survey last year that cohabitation is a “good idea.”

Even with Christians, 41 percent said they see no problem with cohabitation. And sex? The same study reported that 80 percent of unmarried millennial evangelicals have had sex —this means sexual activity among Christians basically matches that of non-Christians.

So Traister’s logic follows: With some 8 million couples currently cohabiting and few, if any, cultural reservations about sex, the functional need for marriage is basically non-existent.

But it’s not quite that simple.

A 2016 study comparing Gen Xers and millennials surveyed more than 12,000 adults across 21 countries. One of the major findings is that the two groups differ when it comes to relationships: American Gen Xers chose good sex (45 percent) as the most important thing in a “good long-term relationship.” But millennials chose friendship (58 percent) over romance and sex.

Added to millennials’ deprioritization of sex is their activity: A study by San Diego State University shows millennials actually take fewer sexual partners than Boomers or Gen Xers.

Last year, VICE asked 2,500 millennials in the U.K.: “What are you most scared of?” A majority (31 percent) most feared never finding love. The percentage of single people who fear never finding love jumps to 42.

Inevitably millennials have been exposed to countless relationships through their lives, but they aren’t experiencing what they consider “finding love.”

***

Corrie and John Mannion are the authors of a new book called Marriages Observed: Millennials Remember, Reflect, and Respond, which combines interviews and conversations between millennials about the marriages they’ve, well, observed.

“In the Christian community, we’re finding a lot of millennials are wanting to find love,” Corrie Mannion says. “They’re wanting to be in a stable, serious relationship or to even get married and have a family.

“I don’t think millennials are really against those traditional things. I think because a lot of the families we’ve grown up in experienced broken marriages and dysfunction, we haven’t received that foundation people do when they grow up in a stable home.”

In many respects, this shouldn’t be surprising. Data suggests more than half of millennials grew up in some form of a broken home.

“Our experience itself with observing marriages has been a lot of broken marriages and broken homes,” John Mannion says. “So the ‘lack of commitment’ [a common accusation against millennial relationships] isn’t coming out of necessarily an illogical place. It’s just the cards we’ve been dealt as a generation.”

Still, the Mannions aren’t fatalistic about love. They think marriage is the solution to some of the obstacles that stand in its way in the first place. Corrie Mannion says they found millennials lacking community—not people to hang out with, but true, deep community, which matches the 58 percent of millennials who named “friendship” their No. 1 relationship priority.

But that level of community isn’t just found. It takes work.

“Learning how to be honest and vulnerable is something that’s so important for our generation,” John Mannion agrees. “Every time we meet people who are in relationships or people who are looking to get married, over and over it comes to a point where it’s like something clicks and they finally realize, ‘Oh, I have to be that honest, I have to be that vulnerable.’

“But millennials have to understand that, because we don’t typically have those kinds of relationships in our lives.”

***

For all the restless selfishness of Mickey and Gus in Love, the show’s co-creators seem to be faring pretty well in love—Lesley Arfin and Paul Rust got married in late 2015.

The irony of the creators of a show cynical toward love ultimately finding it with one another isn’t lost on Rust.

“I’ve certainly had that experience of getting embittered about relationships,” he says. “It’s kind of fascinating how quickly that can go away, though, if you meet somebody who excites you.”