The Bible is the best-selling book of all time and, like any other book, it has some parts that have taken on a sort of zombiefied life of their own. Just as Robin Hood eventually became a rather simplistic story about being good with bows and arrows. Romeo and Juliet has been pared down into a sad story about young love. The nuances of those stories tend to get lost as they float into the broader cultural consciousness.

This happens with the Bible all the time. The story of David and Goliath is turned into a winsome tale about a plucky underdog. Noah’s whole life story reduced to a big boat with happy animals peeking out. And when it comes to specific verses and quotes—like John 3:16, for example—the effect can be downright disorienting. Little pieces of Scripture (“I know the plans I have for you…”) so divorced from their original context that they become little more than inspirational calendar quotes, all but meaningless.

Few more so than “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.” It has such a pleasing, poetic cadence to it that you can understand how it floated into the cultural ether. But without understanding the context around the phrase, which comes from Matthew 22, these words can be twisted into virtually any agenda at all, from advocating for any extreme from taxless libertarianism to socialism.

So let’s start with the actual story. According to Matthew, the Pharisees are out to trap Jesus, sending out a group of their own disciples along with a few members of a sect known as the Herodians. Taxes were a divisive issue in Jesus’ day (duh). Since Rome was an immoral government, many Jews felt it was immoral to pay taxes. The Herodians were a pragmatic bunch, and were generally willing to cooperate. So when the Pharisees asked Jesus about whether or not they should pay taxes, it wasn’t a hypothetical. “Teacher,” they said, “we know that you are a man of integrity and that you teach the way of God in accordance with the truth. You aren’t swayed by others, because you pay no attention to who they are. Tell us then, what is your opinion? Is it right to pay the imperial tax to Caesar or not?”

The trap here was a simple one. If Jesus answers “yes, pay your taxes,” then He loses the support of the zealots who are looking to overthrow Roman rule. If He says no, He loses the support of the more moderate Herodians (and, possibly, gets arrested). But Jesus, very much on to the Pharisees’ game, sidesteps both potential pitfalls.

“You hypocrites,” Jesus responds. “Why are you trying to trap me?”

Jesus borrows a coin from the crowd and asks the Pharisees to identify Caesar’s image on it. “So give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s.”

So the Pharisees were disappointed, as anyone who attempts to use this verse to petition for their preferred tax policy is going to be. Jesus’ financial advice here cuts through specific policy to the way you look at the world, yourself and God.

The first thing to understand is how the idea of an “image” worked in the first century. On our modern coins, the images of George Washington, Abraham Lincoln and the rest are a formality. But images denoted ownership in Jesus’ day. So saying “render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s” here wasn’t just a metaphor; it was literally true. If you weren’t a Roman citizen (like most Jews at the time), then you were given an extra tax in return for the protection of Rome. It was Roman money.

Now that might make it seem like Jesus is pro-tax. After all, he certainly seems to be saying that the money is the government’s anyway, so don’t make a fuss about giving it to them. But as usual, Jesus dovetails this with another note: “…and to God’s what is God’s.”

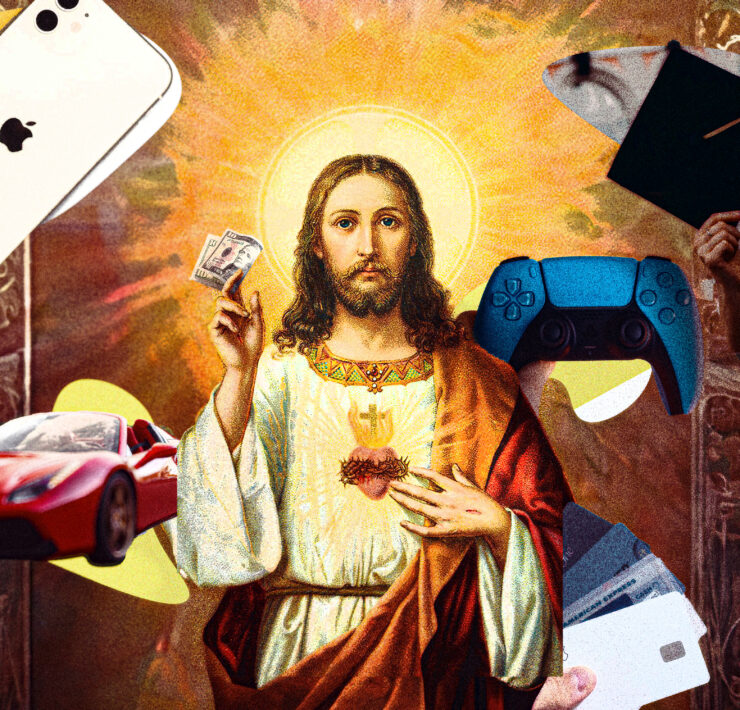

Their money had Caesar’s image on it, so it belonged to Caesar. But human beings have the image of God on us. We belong to God. Whatever value there might be in haggling over where your taxes dollars go, there’s not just more, but infinitely more value in determining where your own self is.

We only have so much say into what happens to our money once it leaves our hands, which is why so much of Jesus’ teaching was around holding earthly possessions loosely. But our hands themselves—and the bodies and souls they’re connected to—those we have a great deal of control over, and should be very concerned about how we’re using something with God’s own image on it. With something that belongs to Him.

Of course, in a broader sense, it’s not just people who have the image of God on them. “The Earth is the Lord’s and all that is in it,” as the Psalmist says. That means that this business of rendering unto God’s what is God’s involves all creation bringing glory to its creator by living according to the way it was designed. For the most part, this process goes pretty smoothly. Fish swim, insects crawl and the moon pulls the tide. These things render themselves to God just by nature of them being themselves. People aren’t so fortunate, since we all too often have to turn from a selfish nature, exercise compassion and cultivate a desire to see justice in the world. When we do these things, we’re rendering our whole selves to God.

And yes, this can involve our taxes, since we do have an obligation to hold our governments accountable to use our tax dollars for things that honor God and His creation. What that looks like will look different for people in different parts of the world. It takes being intelligent and well-informed on the real needs in your area, and how to best equip others to meet those needs. But the dangerous thing is to get so caught up about what and how you render to Caesar that you forget to render to God at all. In this, as in most things, the priority is to seek first the Kingdom of Heaven.

Maybe you’re feeling like you could do some reflecting on your own emotional connection to your money. This blog provides some favorite gratitude prayers to shift your outlook on money.