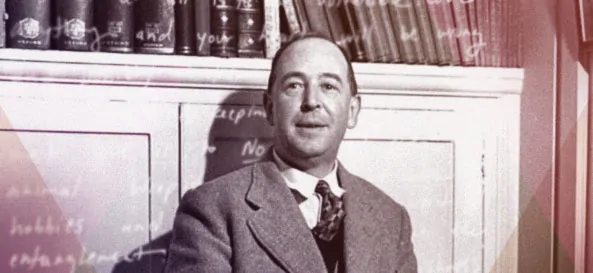

Few figures loom larger over the past century of Christianity than C.S. Lewis, whose rare and beautiful coupling of an indomitable mind and a sparkling imagination make for some of the most gripping writing on Christian thought a person could hope to read. If Lewis’ only achievement had been the creation of Reepicheep, it would have secured his place in literature. Fortunately, he did much more. In fact, he did more than most people realize.

Lewis missed the digital age, which means his great body of work is mostly remembered for the parts of it that have been accepted—not for its controversy. Twitter has made controversy the memorable part of today’s public personalities. Any thought leader who expresses an unpopular opinion is likely to be dismissed entirely, their works thrown in a furnace, they themselves banned, excommunicated and sent off to our social media pillories.

But Lewis did have beliefs that would not sit well with today’s audiences. Indeed, if he were around for his work to by hyper-analyzed by the Facebook theologians, he may well have experienced the ostracization so common for our edgier leaders today.

So here is a list of a few of Lewis’ less orthodox beliefs. These are not listed here to suggest that Lewis ought to be held in lower regard or to diminish his legacy. This is not an attempt to rally an anti-Lewis movement.

Quite the opposite, this is a reminder that his mighty intellect was open to asking questions. No individual’s contributions are invalid just because he had some ideas to which we might not subscribe. We don’t (at least, we shouldn’t) reject Lewis for these beliefs, and we ought to show the same grace to today’s teachers.

An Open View of Genesis

Lewis’ view on the creation account did a good deal of evolving over the course of his life. Even before he converted to Christianity, Lewis expressed skepticism about Darwin’s theories. Following his conversion, he addressed it often enough (although he declined to write the forward for an anti-evolution book.) After he became a Christian, he wrote about the evolution of humanity in The Problem of Pain.

[lborder]For long centuries God perfected the animal form which was to become the vehicle of humanity and the image of Himself …The creature may have existed for ages in this state before it became man …

…But it was only an animal because all its physical and psychical processes were directed to purely material and natural ends. Then, in the fullness of time, God caused to descend upon this organism, both on its psychology and physiology, a new kind of consciousness which could say ‘I’ and ‘me,’ which could look upon itself as an object, which knew God, which could make judgments of truth, beauty, and goodness, and which was so far above time that it could perceive time flowing past.

[/lborder]

Exactly what he believed at the time of his death is open to debate, but he certainly never considered a literal interpretation of Genesis to be a cornerstone of real salvation.

An Inclusive Gospel

The final book in The Chronicles of Narnia features a character named Emeth who had spent his life worshipping Tash (Narnia’s take on a false god) instead of Aslan (Narnia’s Christ figure). However, when Emeth finally meets Aslan, he is told that his service to Tash had really been worship of Aslan all along, on account of his purity of heart.

As the book says,

[lborder] [Aslan] answered, Child, all the service thou hast done to Tash, I account as service done to me. Then by reasons of my great desire for wisdom and understanding, I overcame my fear and questioned the Glorious One and said, Lord, is it then true …that thou and Tash are one? The Lion growled so that the earth shook (but his wrath was not against me) and said, It is false. Not because he and I are one, but because we are opposites, I take to me the services which thou hast done to him. For I and he are of such different kinds that no service which is vile can be done to me, and none which is not vile can be done to him.Therefore if any man swear by Tash and keep his oath for the oath’s sake, it is by me that he has truly sworn, though he know it not, and it is I who reward him. And if any man does a cruelty in my name, then, though he says the name Aslan, it is Tash whom he serves and by Tash his deed is accepted.

[/lborder]

This is not exactly Universalism, as Lewis makes clear, but it is a significantly wider view of salvation than is generally accepted in many evangelical circles.

A Not Totally Inerrant Bible

Lewis believed the Bible was the Word of God, but he did not think that meant every word in Scripture ought to be regarded as literal history. He wrote that most Christians “still believe (as I do) that all Holy Scripture is in some sense—though not all parts of it in the same sense—the Word of God.”

As he wrote in a personal letter:

[lborder]The total result is not “the Word of God” in the sense that every passage, in itself, gives impeccable science or history. It carries the Word of God and we (under grace, with attention to tradition and to interpreters wiser than ourselves and with the use of such intelligence and learning as we may have) receive that word from it not by using it as an encyclopedia or an encyclical but by steeping ourselves in its tone and temper and so learning its overall message.

[/lborder]