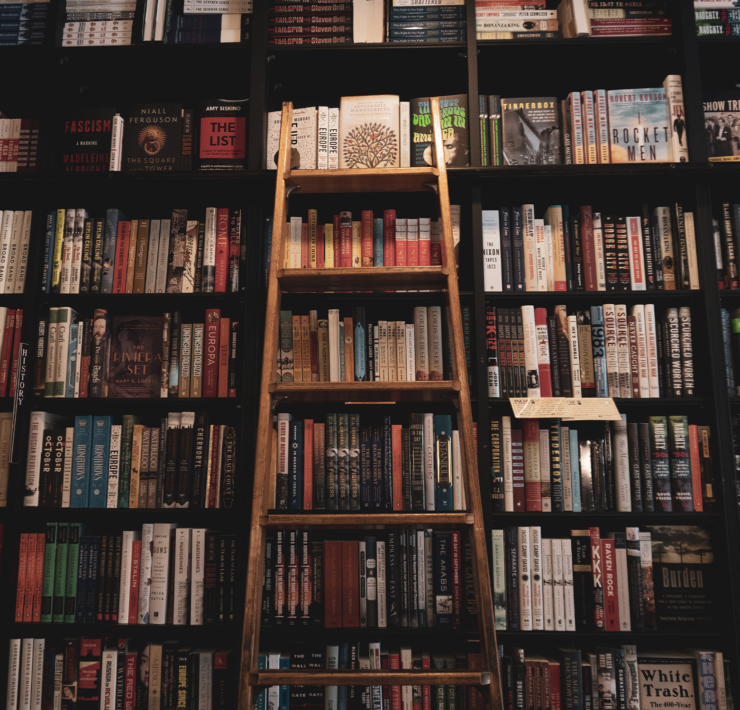

My dream has always been to live in a house full of books. I saw one of those rolling library-ladders in a movie when I was a kid and always dreamed of riding on one someday. My dad is a professor, and I loved visiting his office and looking at all the books on his shelf. They signified a curiosity for truth and an arrival at maturity.

Growing up, I collected my own bookshelves and occasionally just stare at the books on them for inspiration.

My books have surrounded me, comforted me and helped me interpret life.

As a Christian, my books have also helped me make sense of Christ. They’ve taught me truths of the Bible and aided in interpreting tricky chapters or books. As I crossed the stage and took a degree in theology at graduation, I was fairly confident in my beliefs — in large part because of the books on my bookshelf.

The only problem was that my bookshelf was mainly composed by white men. Without realizing, every book I bought was another brick in the wall dividing my whiteness and maleness from others, cementing me into a racism that still blurs my vision from the truth of Christ.

Shaped by History

White men enslaved people. White men used theology to silence minorities and women. White men lynched innocent Black citizens.

Our privilege began before the country was founded and has extended into America today, imbued within Americana along with the Fourth of July and fundamentalism.

I do not represent the worst that my gender and ethnicity have done. But my voice is still conditioned through years and years of privilege and stability. My great-great-great grandfather was a justice of the peace. My great-great grandfather worked as a mechanic. My granddad owns a furniture store. My dad teaches. I’m a grad student. Our family tree has roots which are not obstructed or blocked by slavery, Jim Crow segregation, mass incarceration or voter suppression.

Is it any surprise that my view of the world will be incomplete? Is it any surprise that my definition of suffering will be limited? And with these limitations, my own interpretation of the Bible suffers from lack of perspective.

Whether I want to or not, I bear the history of my race and the history of my gender just as I represent my last name. I’m not defined by them, but I sure am shaped by them.

The Black Christ and a Change in Perspective

I began reading Black Theology last semester because a question refused to leave my mind: How could a people enslaved by “Christians” become Christians themselves? How could they realize the truth of the Gospel that escaped their captors?

I started my search by reading James Cone. He’s famous for making the argument that Christ was Black expressly because Christ was Jewish (God of the Oppressed). To be a Jew in Jesus’ day meant to be oppressed by the Roman empire. Jewish people didn’t have the same rights that Romans had and were marginalized by the empire-at-large. If you had a White person and a Black person standing side-by-side, Christ’s story and perspective would look more like the Black person’s in America.

The things Christ said and the people Christ talked to must be seen in the lens of His world, and perhaps the best people to explicate this aren’t a people privileged in society but those who have been and continue to be systemically silenced and pushed away.

Reading the Bible from One Perspective

After reading about liberation and the Black Christ, I realized that Jesus’ words cannot rely on my sole interpretation or the interpretation of any one, isolated demographic.

I’ve always found great solace in Jesus’ words in Matthew 11:28-30:

Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.

I’ve spent years wanting to carry the yoke of anxiety and fear and have sat in these verses for long periods of time. I firmly believe Jesus speaks to me and each person in their suffering through these verses.

However, I’ve learned to also read this in its literal context: to a marginalized people. This speaks to communities seeking physical liberation and oppression in an unjust society. It is for people weary of being bought, sold, silenced, ghettoed, lynched and shot unarmed.

These verses can and should be spiritualized and applied to suffering in every context, but I cannot use this as an excuse to ignore their literal call to be someone of solace, to seek liberation and to forcibly remove myself from the continuation of unjust systems.

Something Practical

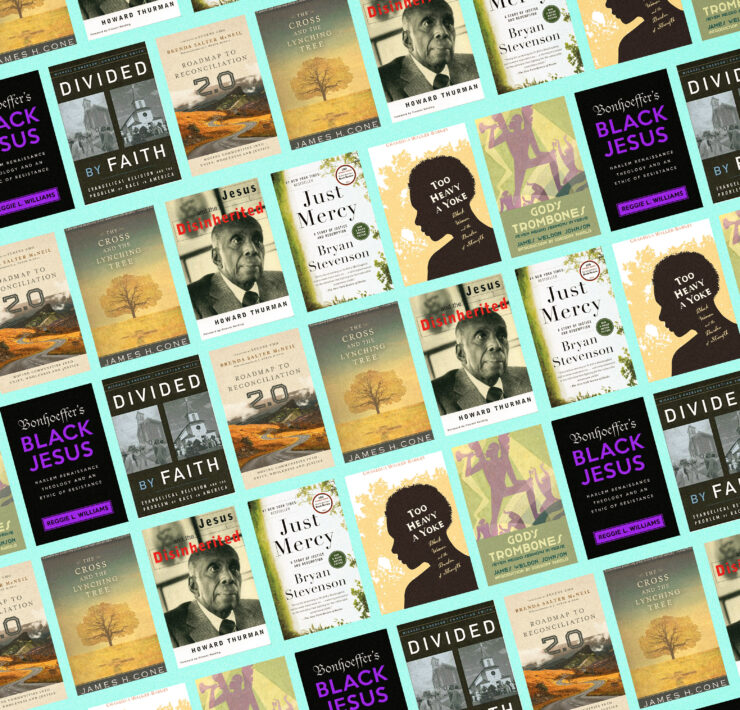

The process of removing myself from racism will begin by not being racist with my books (as well as sexist … but that’s for another article). I’ve only just begun the process, but I’ve found the following books to be really helpful:

- Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson (Spiegel & Grau, 2015)

- Jesus and the Disinherited by Howard Thurman (Beacon Press, 1949, 1996)

- The Cross and the Lynching Tree by James Cone (Orbis Books, 2011)

- Roadmap to Reconciliation by Brenda Salter McNeil (IVP Books, 2016)

- Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America by Michael O. Emerson and Christian Smith (Oxford University Press, 2001)

- Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of Resistance by Reggie L. Williams (Baylor University Press, 2014)

- God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse by James Weldon Johnson (Penguin Classics, 2008)

Do you have any suggestions? My bookshelf is expanding!