It was time for Lenard McKelvey to pay his debt.

Long before he became one of the most popular radio hosts in the country, McKelvey sold crack on the streets of Moncks Corner, South Carolina. But on this night, he had drugs to sell and no buyers. Time was running out.

His creditor offered up a deal: If McKelvey helped him with a home invasion, he’d wipe the slate clean, but there was a problem: McKelvey had such bad anxiety, he knew he wouldn’t kick in a door.

“I moved a bit differently than everybody else,” he says. “I went to jail a few times, but I didn’t get stung like some other people. There were certain things I wasn’t going to do morally.”

Morals or not, McKelvey was trapped, and hours later, he found himself driving the prospective get- away car on an empty Moncks Corner street, inching closer and closer to the marked house he was sup- posed to rob.

McKelvey searched—prayed—for a reason to bail.

“I’m begging to see one set of headlights,” he says. “If I can get one set of headlights in the distance be- hind us, I’m good.”

But it’s the best-case scenario for a robbery, and the worst-case scenario for the young drug dealer be- hind the wheel. All the lights are out on the street, and they’re the only car on the road. McKelvey drives as slowly as he can.

“I peek in the rearview mirror, and way off in the distance, I see one set of lights.”

It’s the cops! McKelvey yelps out a warning and steps on it. His creditor, high and paranoid, ducks in the passenger seat. They peel out of the neighbor- hood, and the boy who would grow up to become Charlamagne tha God survives another night.

“That anxiety saved me in a bunch of different situations,” Charlamagne says. “Being overly paranoid, overly cautious, that was God. He gave me the wherewithal to help me execute the situation. Kicking somebody’s door in has nothing to do with God—He lets you make your own choices—but if you survive, He’ll find you if you ask Him.”

GODSEND

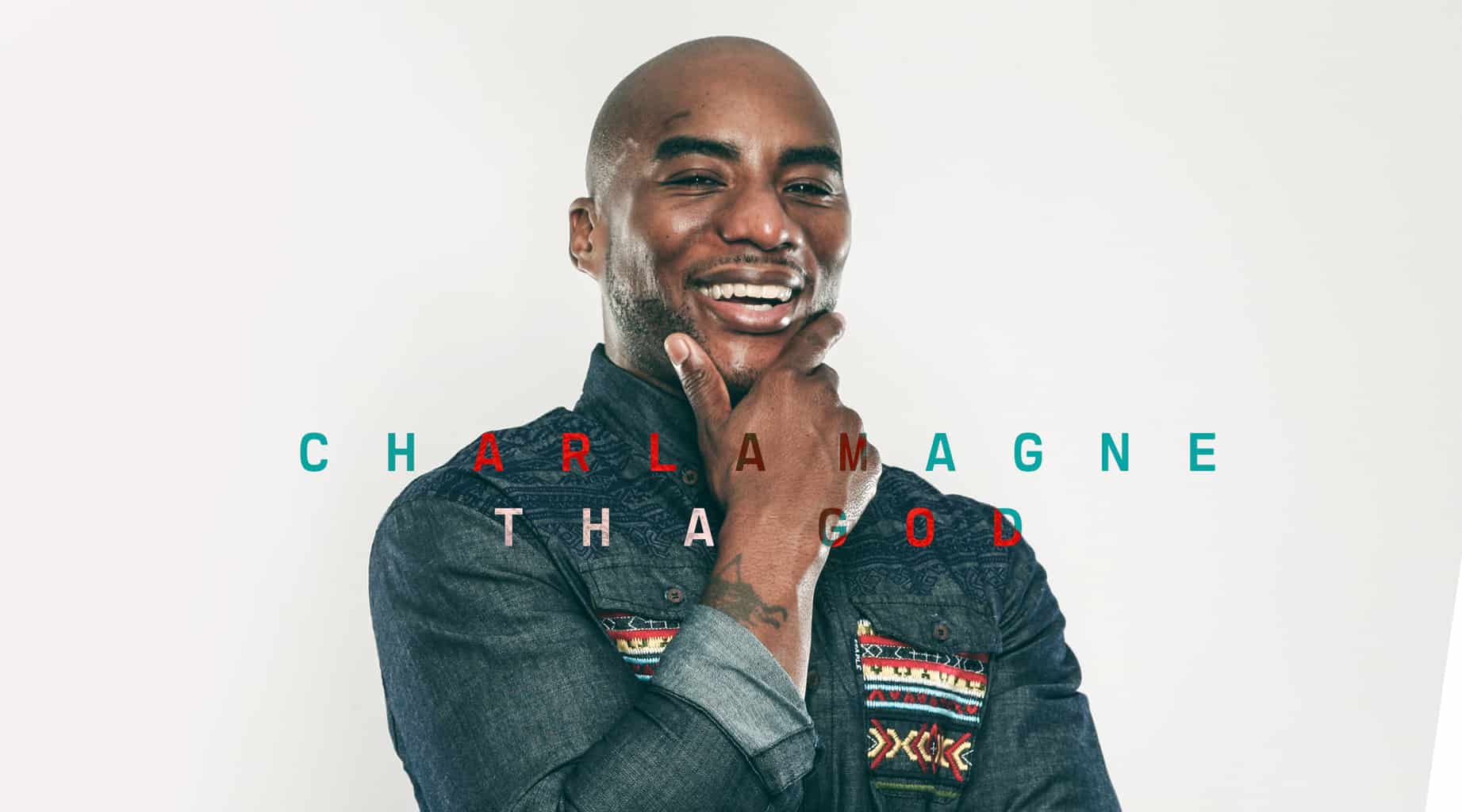

For four hours every morning, Charlamagne tha God and his co-hosts on New York City’s The Breakfast Club hop on the airwaves and interview huge music stars and confess their secrets to over 50 national markets. Billed as “the world’s most dangerous morning show,” The Breakfast Club—featuring DJ Envy and Angela Yee alongside Charlamagne—has spawned memes, trolls and debate thanks to its un- filtered approach to every topic under the sun, from politics and hip-hop to pop culture and faith. Pastors like Carl Lentz and John Gray sit in the same chair as Diddy, Ava DuVernay and Tiffany Haddish. He’s hip- hop’s “go-to guy,” Charlamagne, but the show ruffles some feathers. People love to hate The Breakfast Club, which means they love to hate Charlamagne, too.

“I love getting up every morning and being the first voice a lot of people hear, but I know everybody’s not going to agree with me,” Charlamagne says. “I’m fine with that. My therapist told me I have to release the expectations of people. Whenever I’m bothered about something, it comes from what I expect other people to be doing. All the expectations you need to have are with yourself.”

Charlamagne writes at length about his formula for success in his best-selling book Black Privilege: Opportunity Comes to Those Who Create It. In a world of filtered, politically correct opinions, filtered social media pictures and filtered projections of ourselves, Charlamagne is entirely unfiltered. The host is not afraid to be wrong, and he’s not afraid to be vulnerable.

In conversation, Charlamagne brings up his therapist, criminal background, faith and family history without the slightest provocation—but that honesty has a dangerous side. Guests have walked out on his confrontational interview style (most famously Birdman in 2016, shouting, “Put some respec’ on my name”), and Charlamagne’s bold diatribes often land him in hot water. His “Donkey of the Day” segment has targeted the president, “Kanye Kardashian” and football star Odell Beckham Jr., among countless others.

Charlamagne’s attitude makes some public backlash inevitable, but he stays afloat. Even when he’s taking shots, he never stops firing back.

“People don’t expect mistakes anymore,” he says. “Everyone’s trying to keep up with this manufactured illusion of themselves instead of being the real them. I’m comfortable knowing who I really am, and I’m not afraid to learn. Life is a process, so part of that struggle may be some growing pains.”

Charlamagne tha God has seen plenty of those.

The Road to Breakfast

Though Lenard McKelvey dodged the law on the night of the home invasion, he was arrested multiple times in Moncks Corner. His crimes ranged from assault to drug possession.

After his third trip to jail—a 41-day stint when he was a teenager—Charlamagne started taking night school classes and found an internship with a local radio station. He was hooked. He built a good relationship with one of the programmers and began scrapping for air time. In 2005, he secured his first full-time hosting gig in New Jersey.

The long-awaited success taught Charlamagne a lesson he’d preach from that day on: If you want to change your circumstances, you have to be willing to work for that change—no one will do it for you.

“Oftentimes, we don’t realize that destiny is a matter of choice,” he says. “That’s the process of life. I don’t know who told people you go right from one to 10. You have to go through two [through] nine, and when you get that blessing, you have to know exactly what to do with it. I believe in my God. When I make poor choices, I turn to God to help me through that.”

Charlamagne grew up on what he calls a “foundation of spirituality.” His grandmother was a Baptist, his mother was a Jehovah’s Witness and his father is a convert to Islam from the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Charlamagne is an avid Bible reader himself. He quotes Scripture often in conversation (“Romans 8:31: ‘If God is for us, who can be against us?’ I believe in a mighty God. That’s who I submit my will to every day.”), and he often appears alongside church leaders both on and off The Breakfast Club. This past winter, he worked with Elevation Church pastor Steven Furtick on a documentary about race, purpose and faith. (They went to high school together but weren’t friends.)

Whenever someone brings acclaim to The Breakfast Club—its popularity, its influence, its pervasiveness— Charlamagne has a reflexive answer: “Praise be to God.” Maybe it wasn’t Charlamagne doing all the work on his road to fame.

Charlamagne is caught up in another book right now besides the Bible: Rob- in Stern’s The Gaslight Effect. It’s about how the negative perceptions of others can infect your thinking until you begin to interpret their viewpoints as truth.

Charlamagne describes it like looking in the mirror and seeing a distorted reflection of yourself—a legitimate mental health struggle—and it’s something he battles to this day in therapy.

“As a man, there’s a lot of things I haven’t dealt with,” he says. “For a lot of my life, I was self-medicating with weed and alcohol, thinking I don’t have time to deal with this right now, but certain things bug you out.”

Charlamagne details a list of issues that could fill entire books: sexual abuse, rape culture, misogyny, fear. “That was all normalized for me, but none of it was normal,” he says. “I’ve unlearned a lot of that. The Bible says when you were a child, you thought like a child, but when you’re a man, you act like a man, you think like a man.”

The Magne Thing

The Breakfast Club has become one of the most important tentpoles of hip- hop culture, and that makes Charlamagne one of the most important people in hip-hop culture.

For a young artist to land a Break- fast Club interview is like a rock band earning a spot on the Ed Sullivan Show. It might be seen as a do-or-die, make- or-break moment, but Charlamagne’s internal philosophy is softer than the interrogation tactics he brings to the show.

“I’m not a gatekeeper,” he says. “If you’re looking at yourself like that, you’re thinking way too highly of yourself. I’m a fan. I have a sense of discovery every day, and that allows me to care about people’s stories. I don’t feel like I have any power, I just have a platform. The Breakfast Club is not my show. That’s our show. It’s for everybody.”

The Breakfast Club has one of the most inclusive guest lineups on radio. Late comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory sat in the same chair as world-famous superstar Kendrick Lamar, and Kendrick Lamar sat in the same chair as social activist and transgender actress Janet Mock.

Mock’s interview in particular was controversial. Some accused The Breakfast Club of insensitive lines of questioning, and when a later guest made transphobic jokes against Mock, the show was criticized for going along with the humor. Charlamagne has renounced the offensive rhetoric that materialized around Mock’s appearance, but the incident did some damage. Now, it’s another opportunity to learn.

“If you can’t look back on your life and see where you made mistakes, something’s wrong,” he says. “I don’t know anything about Janet Mock’s world, so why not have a conversation with her? She’s a human being like everybody else.”

Now, Charlamagne finds himself in a position where he can lift others up and place them alongside him on that platform, but that’s a complicated space to navigate in 2018.

“I have a lot of people coming to me when they have problems and when they’re going through things,” he says. “I’m the go-to guy for a lot of people, but who does the go-to guy go to?”

The go-to guy goes to his therapist. When he feels the world gaslighting him and forcing a delusion in front of his eyes, he looks in the mirror and acknowledges his mistakes. That empowers him to have confidence.

The go-to guy goes to the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He hopes for a world where people are judged on their character. That empowers him to search for empathy.

The go-to guy goes to God. He owns his past and owns his sins, but he of- fers praise for every blessing. He says whenever he steps outside and takes in the sky, the vastness of the world, it humbles him. That empowers him to be content, and if you’re not with that, Charlamagne tha God doesn’t care.

“You should be comfortable knowing the truth about yourself,” he says. “You can’t grow if you’re being delusional. If others never believe the truth about me, I’m good. That’s how I move. I don’t have beef with nobody but the devil.”