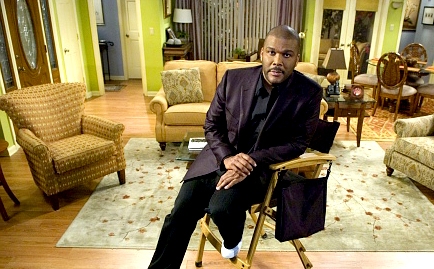

Since exploding onto the nation’s movie screens from seemingly nowhere in 2005, Tyler Perry has created a media empire that has been nearly unprecedented in movie history. Certainly no other African-American filmmaker has ever attained his level of clout, as Perry has written, directed, produced and starred in 11 films since his first: Diary of a Mad Black Woman.

But with such wild success has come wild controversy, for the centerpiece of Perry’s success has been his portrayal of a character named Madea. She’s a wise-cracking, comedically abusive and pot-smoking older lady, which means that Perry is playing her in drag—a fact that some other black filmmakers like Spike Lee have criticized, accusing Perry of being too uncomfortably close to racial stereotypes of the past.

At a press event for Perry’s newest film Madea’s Big Happy Family, which came out on Friday, Perry addressed Spike Lee’s criticisms in a most unexpected fashion—by railing at me for a question I was making about a completely different kind of potential backlash. I wanted to know if the black churchgoing community that make up his strongest fan base—for Perry’s films are all rooted deeply in Christian themes and values—are likely to give him a backlash over the amount of marijuana use and comments about the drug in the new film.

The movie itself is hard to review, as it’s filled with Perry’s usual mix of wildly conflicting emotions of happiness and sadness, faith and despair, and is often over-the-top due to its prior history as a stage play in which the actors all played loudly to the back seats of theaters nationwide. Basically, look at the commercials and trailers and you’ll know immediately if it’s for you or not.

But Perry’s outraged response—keyed to his misunderstanding my question—caused national news on countless film-related websites.

You’re in the character of Madea in costume more than any of your other movies. How challenging was it to direct at the same time?

Perry: It wasn’t challenging for me because I worked with a lot of the same people as before. So my team knows it’s me calling the shots when in costume. But I’m sure for the new people it’s strange seeing me stand there in the wig and costume going, "OK, move over here," and then saying “Action!" and I’m in the middle of the scene with them. It’s very interesting, but it worked well.

How do you decide is too much Madea—how do you balance giving the audience what they want with her while still telling your other stories in the film?

Perry: This one was easy for me because I’d already done the show 125 times on the road in live performances. Cassi was right there with me in the first leg of the tour. The live audience told me what they wanted to see and what they didn’t. But the truth is this is more Madea than any of them combined, because after Colored Girls and Why Did I Get Married Too I just wanted to have some fun and really enjoy myself.

Do you ever get any flack …?

Perry: I knew this was coming—flack about what?

Not about Madea. No, a lot of your audience is church folks, I was wondering if they give you a hard time about pot jokes?

Perry: I was really ready to get you. I thought you was going to ask about Spike Lee. I’m so sick of hearing about d— Spike Lee. Spike can go straight to hell! You can print that. I am sick of him talking about me, I am sick of him saying, “This is a coon, this is a buffoon.” I am sick of him talking about black people going to see movies. This is what he said: “You vote by what you see.” As if black people don’t know what they want to see. Spike needs to shut the hell up … I’m so sorry I jumped on you.

(Somewhat joking) I’m scared now.

Perry: On this one I pushed the envelope a little bit. Something happens to you at 40, and when you lose your mother, you get to this place in your life where you’re like: “You know what? It don’t even matter.” Don’t take things as serious as I used to. I pushed the envelope a little bit. I know some church folks are gonna be like, “Oh,” but I have some who have a problem every time I say “hell” in one of the shows. So there are some who will think it’s too much, but then there are others who know that Madea is not the Christian in the movie, but the Christian themes are in there. So sorry, so sorry! I just thought Spike Lee was in the air.

You talk about some health concerns like diabetes and prostates. How challenging was it coming up with material that would satisfy old fans while still drawing the interest of new ones?

Perry: People say, "Where do your stories come from?" Well, I’m black and I live in a neighborhood where I sometimes walk down the street and see things. For instance, with the fast-food scene here, one time I drove up to a drive-thru at Burger King in Atlanta, pulled up the window and ordered a Whopper and the lady said, “We ain’t got no meat.” You can’t make that stuff up, man. That’s where the whole Madea fast-food scene came from. So being able to have all those kinds of experiences, be around people who are around all kinds of things and will tell you the truth. This was borne out of me needing a place to release after my mother died. I wrote it and went on the road with it, and then many other things my family was going through at the time. I shut everything down and went on the road instead of shooting Colored Girls. Nobody prepares you for turning 40 and for that kind of grief. And together is a combination.

What inspired the letter yesterday?

Perry: Going into this junket. I was writing in an open email about people and how hard people work to discourage people from seeing my work. This is where the Spike Lee thing comes from—that this is Stepin Fetchit, this is coonery or buffoonery. They try so hard to get people aboard with them in this mob mentality, to come against what I’m doing, but this is what I want to make clear to everybody, especially black people: I’ve never seen Jewish people attack Jerry Seinfeld and say, “This is a stereotype.” I’ve never seen Italian people attack The Sopranos. I’ve never seen Jewish people complain about Mrs. Doubtfire or Dustin Hoffman in Tootsie. This is not something I can undo.

Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois went through the exact same thing; Langston Hughes said that Zora Neale Hurston, the woman who wrote Their Eyes Were Watching God, was a new version of the “darkie” because she spoke in a Southern dialect and a Southern tone. And I’m sick of it from us; we don’t have to worry about anybody else trying to destroy us and take shots because we do it to ourselves.