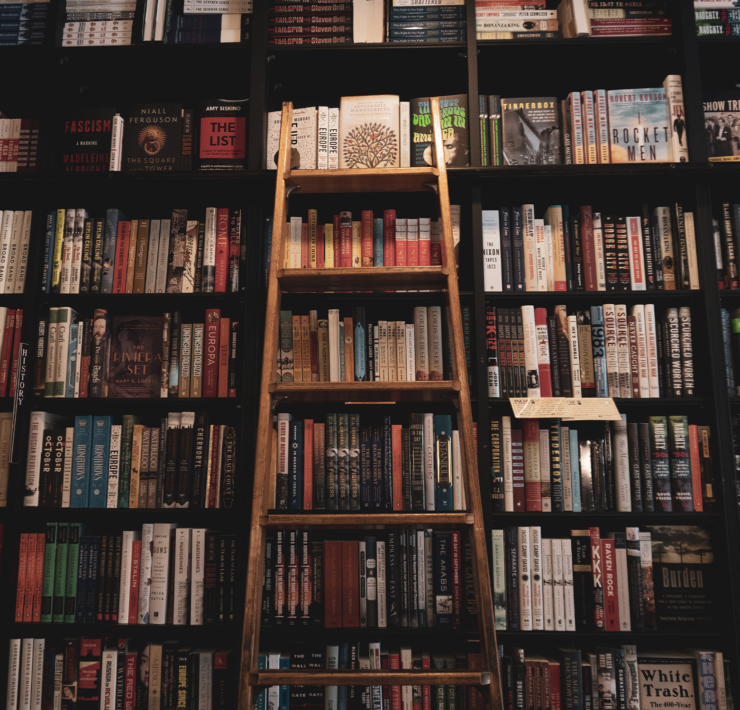

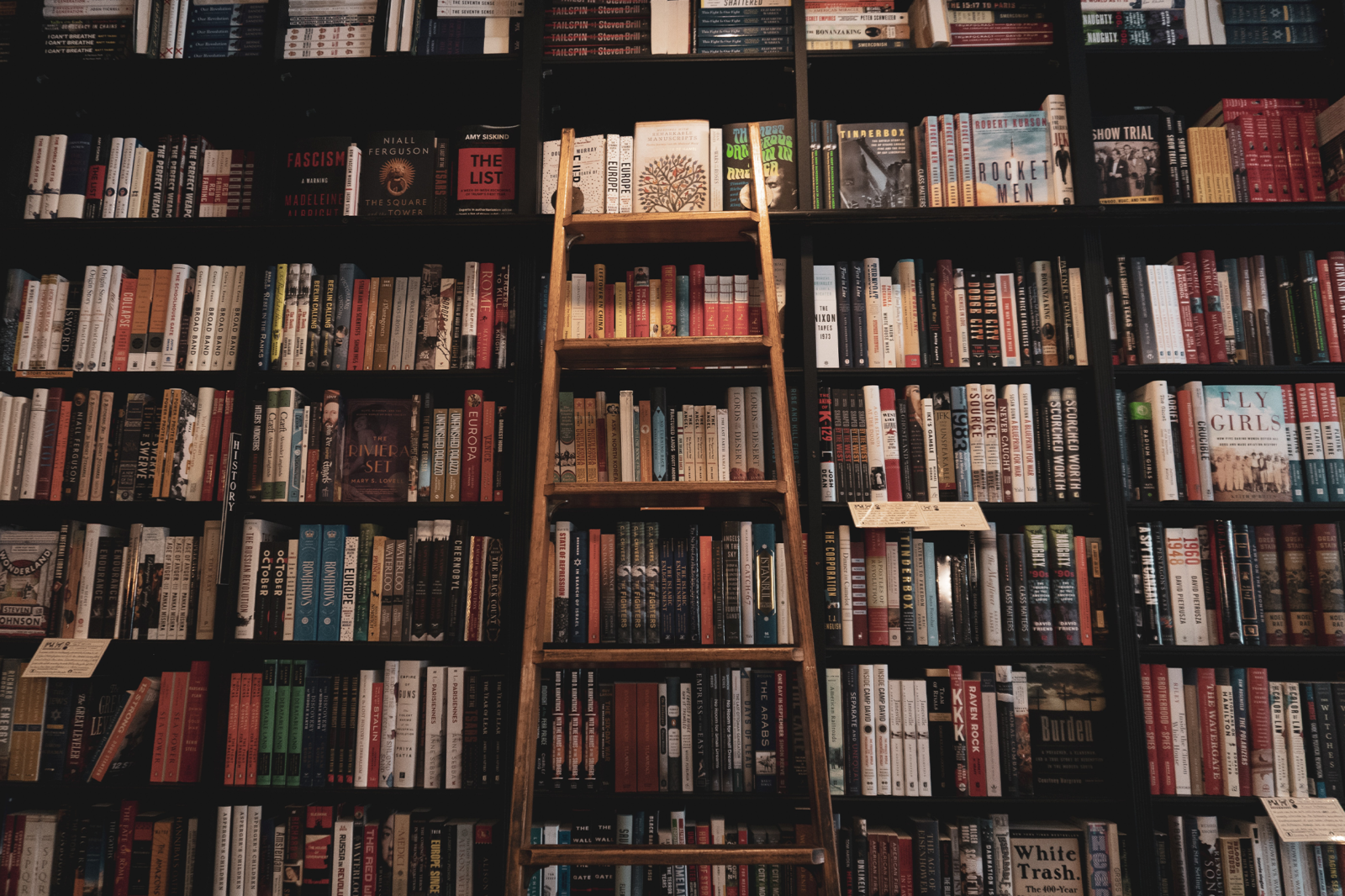

Earlier this month, the American Library Association said book banning efforts reached an unprecedented level in their time of documenting such efforts. They counted 729 challenges to books available in libraries, schools and universities, a huge jump from just 156 challenges the previous year. In 2019, there were 377. In all, 1,597 different books were threatened with a ban in 2021.

“We support individual parents’ choices concerning their child’s reading and believe that parents should not have those choices dictated by others,” said ALA President Patricia Wong in a press release. “Young people need to have access to a variety of books from which they can learn about different perspectives.”

So, why are people trying to ban these books?

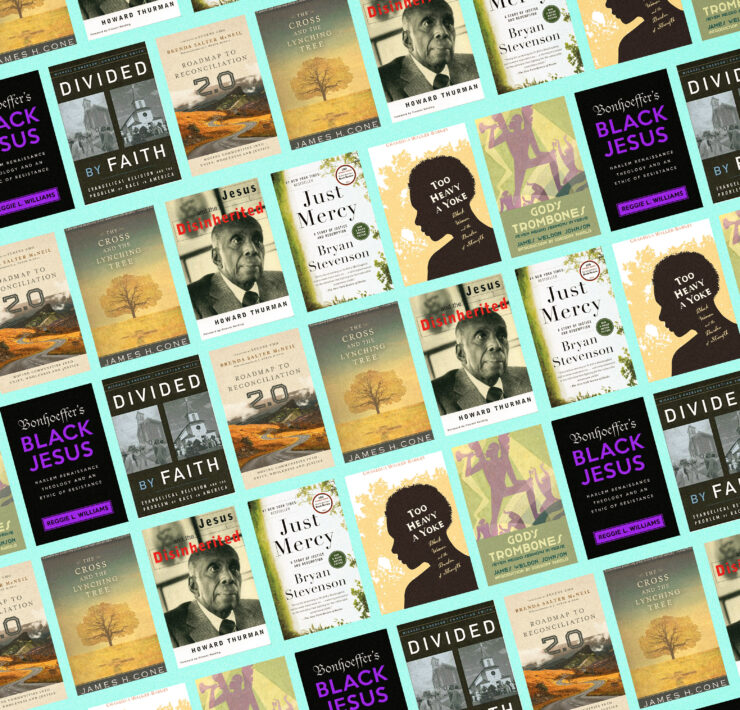

Many (though not all) of the books in question focus on themes of racial identities and sexual orientation. Efforts to ban or otherwise limit access to them are often tied, directly or otherwise, to political controversies around things like Critical Race Theory and LGBTQ equality. Books like Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give and David Levithan’s Two Boys Kissing are drafted into a culture war in which depictions of the Black experience in the U.S., non-gender conforming relationships and other subject matter are seen as pushing certain agendas.

Tell me more about these books.

Over 1,500 books have been targeted by various bans at the state and local levels, and they run an enormous gamut in terms of content. Some, like Dr. Carrie Leff and Dr. Lisa Klein’s Celebrate Your Body 2: The Ultimate Puberty Book for Preteen and Teen Girls, simply contain frank drawings and descriptions of changing bodies that are deemed “pornographic.” Others, like Ashley Hope Perez’s Out of Darkness and Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, were targeted because some considered its raw depictions of sexual abuse to be inappropriate. Many more were put on blast for centering on the experiences of LGBTQ people.

Who, exactly, wanted these books banned and what does “banned” mean?

Again, it’s a pretty broad list, but experts say this recent push to ban books is unique from past challenges in that it’s being driven less by private citizens and more by political groups who have the organization and resources to elevate these efforts into legitimate challenges. Social media campaigns whip up numbers who can then move these concerns forward in a way past challenges could not.

In many cases, the attempts came from political leaders and education officials. In Wyoming, a county prosecutor’s office weighed charges against library employees because the library has books like Sex Is a Funny Word. A bill was introduced in the Oklahoma State Senate that would prohibit stocking books that focus on sex and sexual identity. In Tennessee, the McMinn County Board of Education voted to remove Maus from an eight-grade module on the Holocaust.

So “banning” often means limiting or outright denying access to such books in places where kids can get their hands on them.

Why do they want these books banned?

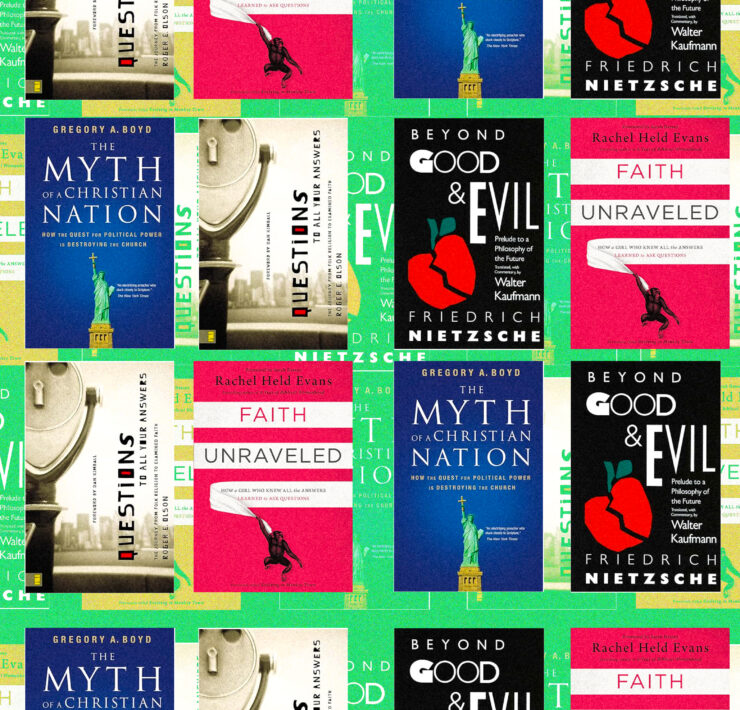

Some groups say books like Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale contain certain perspectives and opinions they don’t want their kid reading. A group called No Left Turn in Education says such books are “used to spread radical and racist ideologies to students.”

For example, The 1619 Project is an enormously popular target for its historical evaluation of slavery in America — an evaluation that argues slavery played a far more central role in the formation of the United States than has been popularly acknowledged. In this telling, the triumphant vision of America’s Founding Fathers throwing off the chains of tyranny to become a “shining city on a hill” runs up against the fact of how much of America’s founding owes to the oppression of Black men and women forced into labor.

But the broader issue is one of parental control. Parents’ rights groups say parents have the right to determine what their kids do and don’t learn about, particularly when it comes to sensitive issues like sex. “The bottom line is if parents are concerned about something, politicians need to pay attention,” said Tiffany Justice, a former school board member and co-founder of Moms for Liberty, in an interview with the New York Times. “2022 will be a year of the parent at the ballot box.”

OK. So what’s the pushback?

There are general concerns about providing children with a wide variety of perspectives and just general concerns about fostering a culture of open thought in which parents guide their children responsibly instead of banning all alternative views. More specifically, other groups say that banning these books restricts the rights of parents who do want their kids to read these stories. They say that parents who don’t want their children to read such books can reach out to teachers individually and ask for an exception.

“By attacking these books, by attacking the authors, by attacking the subject matter, what they are doing is removing the possibility for conversation,” author Laurie Halse Anderson told the New York Times. “You are laying the groundwork for increasing bullying, disrespect, violence and attacks.”

This all sounds awfully partisan.

Mostly, but not exclusively. While it’s true that most of the pressure to ban certain books has come from conservative groups, John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird are both frequently challenged for their handling of racial issues, and those challenges tend to come from more liberal groups.

But major political figures on the right have definitely seen this as an issue worth focusing on, with Texas Governor Greg Abbott calling on his education agency to “investigate any criminal activity in our public schools involving the availability of pornography.” In Ridgeland, Mississippi, the mayor refused to give Madison County Library System their funding until the libraries got rid of any books with LGTBQ themes.

So, it’s not strictly partisan, but the political culture war lines are definitely there.

Where is this going?

In its most extreme forms, these bans are getting wrapped up in issues like Florida’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bill and the attempts of certain figures to paint public school teachers who include these books in their curriculum as “groomers.”

But it’s hard to say what the endpoint of all this is. Book bans are hardly new, even in recent history, so it’s possible that this particular culture war will go the way of many that have come before it once its loudest proponents get bored and move on to the next skirmish.