Editor’s Note: The video discussed in this piece contains some graphic content (gun violence) and strong language, neither of which represent the values of RELEVANT. However it is at the center of an important cultural conversation about racism, gun culture and media culture, so we find it appropriate to weigh in. It can be viewed here. Last night, it won Song of the Year and Record of the Year at the Grammys.

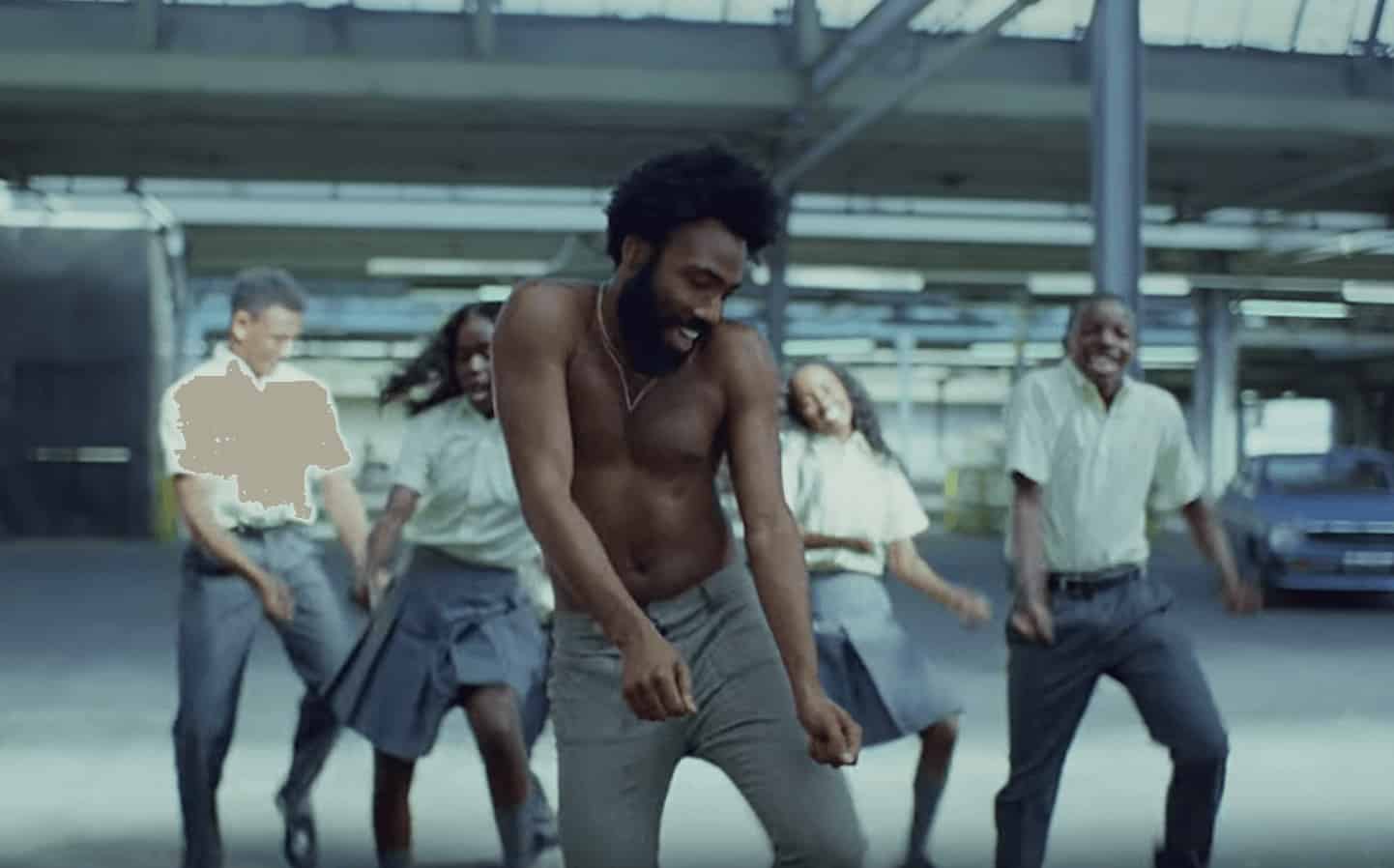

In the visual for “This Is America” Childish Gambino glides through scenes of mayhem and joy. It sits at the epicenter of a deluge of controversy and think pieces like this one. It has been praised by some as a work of genius, warranting multiple viewings and detailed exegesis. It has been critiqued for its gratuitous violence, as normalizing black death. But hopefully all can agree that the music video is reactive, offensive and important.

I want to go further and say that the visual for ‘This is America” is prophetic. But before I explain what I mean by that, I’ll explain what it doesn’t mean.

Prophets Aren’t Perfect

To say that ‘This is America” is prophetic is not necessarily praise. Prophets are not perfect and prophecy is not necessarily special. The Christian Scriptures make this clear.

Caiaphas, the high priest, who played a key role in the plot to lynch Jesus prophesied (John 11:51). The mad king Saul, who obsessed about killing his son’s best friend, David, also prophesied (1 Samuel 11:10). And just to prove a point about who can prophesy, God sent the Holy Spirit on a crowd of 72 Israelite leaders who remain unnamed, causing them to prophesy (Numbers 11:29). So to act as a prophet from time to time is not the exclusive prerogative of a few holy men and women. As far the Christian Scriptures are concerned, any [donkey] can prophecy (Numbers 22:21-39).

Prophets are often imperfect vessels. They have their moments of inspiration, but the rest of the time, they’re as fallible as anyone else. So to say that “This is America” is prophetic is not the same as saying “Everything Childish Gambino does and says is immaculate.” It also doesn’t mean that Donald Glover is a Christian.

But it means that this piece of art recalls a tradition of frustrated messengers, grabbing a society by the collars and trying to shake it awake by any means necessary. Dr. Christopher B. Hays, associate professor of ancient Near Eastern studies at Fuller Theological Seminary, recalls a story to demonstrate the extreme lengths to which ancient prophets would go. A prophet from the ancient civilization of Mari, he relays, is said to have stood at a city gate and demanded a lamb which he devoured alive once it arrived. Shocking performances like that, commonly known as “sign-acts” are the stuff of the prophetic tradition: reactive, dramatic, offensive and important.

The prophets of ancient Israel also employ dramatic, offensive, creative acts to raise awareness about the injustices of their society and the consequences of those injustices. The prophet Isaiah literally sings a litany of social ills for which the judgment of God is coming upon his countrymen and women:

[lborder]Woe to you who add house to house

and join field to field

till no space is left

and you live alone in the land …

to those who call evil good

and good evil …

who acquit the guilty for a bribe,

but deny justice to the innocent (Isaiah 5:8, 20, 23).

[/lborder]Each “woe” in Isaiah’s prophetic song, explains Dr. Hays, is a Hebrew particle (hôy), a commonly used ancient Israelite “funerary cry, [usually] used to mourn people after they’re already dead.”

Hays says that Isaiah’s mode of social critique could be read as mocking at times, and wonders aloud if perhaps this mocking pronouncement of a dead society—his society—may convey the prophet’s attitude toward his people. Had Isaiah given up on Israel?

Childish Gambino’s Raw Lamb

I first suspected that Donald Glover, Gambino’s alter-ego, was among the prophets while reading his interview earlier this year with The New Yorker. “I feel like Jesus. I do feel chosen,” Glover told the magazine. “My struggle is to use my humanity to create a classic work—but I don’t know if humanity is worth it, or if we’re going to make it. I don’t know if there’s much time left … It’d be nice to feel less lonely.”

There is so much greater context to that interview, and I relay those words not assuming I grasp their full meaning but sharing how they fell on my ears. I heard an echo of Jeremiah who wondered if he should even bother prophesying anymore (Jeremiah 20:9), and Elijah who felt very much alone (1 Kings 19), and Isaiah who may have thought his people were too far gone (Isaiah 53:6), but all these messengers still felt compelled to deliver the truth.

Glover warned us in that interview that he had something he felt compelled to say. It sounded like the message was something like a burden, something he had reason to believe people would resist. To be honest, I hadn’t suspected that weeks later the man who gave us Redbone would, in his own way, devour the proverbial lamb to get his point across.

The Shortest Analysis of “This Is America” on the Internet

At the start of “This is America” the gleeful singing of children is interrupted by a homicide. A black man with a bag over his head is seated where a guitar player had just been plucking out bright South African rhythms on a nylon guitar.

Enter a shirtless, writhing Childish Gambino, who slinks over to the man’s backside, carefully pulls out a gun and assumes the position of an infamous Jim Crow poster and shoots the faceless victim in the back of the head. “This is America,” Gambino announces as a child runs in from stage right to carefully retrieve the weapon, wrapping it in some kind of cloth for protection. The video could have stopped there.

Already, the rapper has dramatized an uncomfortable truth about black life in America: what some refer to as black “fungibility.” A fungible item is one that can be easily replaced by another identical item: like a dollar. Every dollar has a serial number that nobody cares about, because dollars are interchangeable, replaceable, fungible. A comparison may be useful to see how this applies to black life.

Consider Brock Turner, a young white man who was let off the hook after raping a young woman because the judge did not want to “ruin his future.”

Consider the attention given to Brock Turner’s specific humanity that saved his life. Now compare that to the death of Philando Castile, a black man stopped and killed by a local Minnesota police officer because his “wide-set nose,” a description vague enough to apply to millions of black people, allegedly fit the description of a robbery suspect. You could have literally swapped out just about any black man for Castile to fit that description. This is America, indeed. Where Brock Turners are one-of-a-kind people with specific worths and futures that need protecting. But Philando Castiles are easily replaceable.

Who is the man that Gambino shoots in the back of the head? Is it the guitar player? Is it someone else? The bag over the man’s head makes it impossible to tell. And ultimately, in America, this detail often doesn’t matter.

But Glover gives his audience no time to reflect on the murder they’ve just witnessed. Seconds later he’s body rolling away from the crime scene, smiling, rapping and doing the Gwara Gwara (a popular South African dance) with schoolchildren—all of this while police chase civilians with their batons drawn, people rummage through vehicles as though possibly looting, and one of the four horsemen of the Apocalypse goes galloping by in the background. Yes. This is America, where the world is on fire, but people are too distracted by pop culture to notice.

And Gambino, in “This is America,” is both a black agent of violence and instigator of joyous distraction, both living vestige of Jim Crow and woke messenger. The visual resists pristine, systematic interpretations. And these conflicting roles that overlap cause one to wonder if Glover meant to juxtapose the realities of black-on-black crime (the murder of the “faceless” black man), black people who participate in anti-blackness (the Jim Crow poses), and the terrors systemic racism (the officers chasing civilians and the police car following the apocalyptic horseman), all at once.

When asked, he demurs. “I just wanted to make a good song,” he told E! News on the red carpet of the 2018 Met Gala. “Something people can play on the Fourth of July.”

The Cost of Confronting Nationalism

Glover’s refusal to pontificate makes it fair to guess that he would not appreciate being called a prophet—although he does so with a smirk, suggesting that he knows exactly what he’s done. Prophets are often reluctant to wear the mantle. Moses asks God to find someone else (Exodus 4:13). Jeremiah says he’s too young (Jeremiah 1:6). Jonah runs as far away as possible (Jonah 1:3).

It makes sense. People generally don’t like or listen to what prophets have to say. The archetypal prophet, Cassandra of Greek mythology, was given her gift by the god Apollo. But when she curved the sun god’s romantic advances, he cursed her, ensuring that nobody would ever believe her completely accurate warnings. That’s the prophetic gig.

The messages the prophets mean to deliver ask a lot of their audiences. When Isaiah sang that funeral song about ancient Israelite society—“This is Jerusalem!”—it was jarring and offensive to his neighbors. Israel was, according to their history, God’s special possession (Exodus 19:5). God had promised that they’d dwell in their land under divine protection (Deuteronomy 28:1-7). And God promises to be an enemy to their enemies (Genesis 12:1-3).

But Isaiah sang to them that because of the social injustices that persisted in the land, God was going to allow them to be deported by an invading international power (Isaiah 5:26-30). Jeremiah’s message was similar, as was Amos’, as was Ezekiel’s (Jeremiah 7; Amos 7:1-17; Ezekiel 23). And for this reason, people regarded these messengers as traitors (Amos 7:10; Jeremiah 38). People listened to them and basically said: “How dare you talk about our country that way! How dare you blaspheme God’s temple by calling the priests corrupt! How dare you say that God would judge us!”

In his book, The Prophets, Rabbi and philosopher Abraham Joshua Heschel writes:

From the beginnings of Israelite religion the belief that God had chosen this particular people to carry out His mission has been both a cornerstone of Hebrew faith and a refuge in moments of distress. And yet, the prophets felt that to many of their contemporaries this cornerstone was a stumbling block; this refuge, an escape. They had to remind the people that chosenness must not be mistaken as divine favoritism or immunity from chastisement, but, on the contrary, that it meant being more seriously exposed to divine judgment and chastisement.

[/lborder]And like the lamb-swallowing prophets of Mari, the ancient Hebrew prophets resorted to dramatic sign-acts. Jeremiah bursts into a royal meeting with an ox yoke on his back to symbolize the coming “yoke” of Nebuchadnezzar (Jeremiah 27-28). Hosea marries a cultic prostitute to illustrate Israel’s unfaithfulness (Hosea 1-3). Isaiah walks around naked for three years to show the coming shame of God’s judgment (Isaiah 20).

They are a bit over the top. You can imagine their neighbors saying, “Sure. I get that Isaiah wants to make a point but why does he have to take his clothes off to do it?” These were offensive performances in their day. And the critiques they offer are the ancient equivalents of undermining America’s gun culture, racism, police brutality, materialism and distracting pop culture, like Glover does in the “This is America” video.

“[The prophets] all do these socially bizarre things,” says Dr. Hays. “I think that Glover’s work is in line with that. Glover has offended both of the ‘true’ tenets of so-called American Christianity which is nationalism—white nationalism really—and racism. Nineteen percent of white U.S. evangelicals didn’t vote for Trump but nonetheless 81 percent of white evangelicals did.”

“[The video suggests] that the U.S. is not some special project of God” Hays continues. “There are things that we do well that are worth pointing to and praising, but on the other hand the idea that we are above critique is a problem of American Christianity.”

Years after the prophets are gone, they are often regarded as heroic exemplars of courage for taking a stand for something they believed in. But it’s important to note that the consequences for confronting nationalism can be dire.

According to tradition, many of the ancient Hebrew prophets died as martyrs, because of the offense of their work: Amos is said to have been tortured; Jeremiah is said to have been stoned to death; Isaiah is said to have been sawed in half; and Zechariah is said to have been killed on the temple grounds.

It’s often suggested by New Testament scholars that the reason Jesus, whom Glover told the New Yorker he identifies with, went about commanding people He’d healed not to say anything, and often demurred to directly identify Himself as Messiah was because He was well acquainted with the risks of the prophetic life (Mark 1:41-42; Mark 8:30-38).

If their message didn’t cost their lives, it still carried a kind of social tax. Prophets were often labeled as crazy (in fact, the Akkadian word for prophet, muhu, means “crazy person”), demonized, drunkards, if not dangerous, subversive radicals. All of these reactions—labeling, ignoring, attacking, dismissing—are ways the people have been trying to avoid the prophets for centuries.

With the risks and challenges considered, it’s understandable that many prophets don’t want to be prophets. Reluctance may be the key indicator that we’ve spotted one.

“This is America” is prophetic work because it tells the dirty truth about a violent, distracted society. But it’s better for Glover if millions of people discuss among themselves how “This Is America” is speaking to them than for him to climb on a soapbox and start preaching. The headlines would start being about the artist—“Is Donald Glover a radical?”—rather than the art.

Seeing the Cycle in Real Time

Although, in some ways, the prophetic endeavor seems to be doomed from the beginning, the prophets must deliver the truth with which they’ve been burdened. They must do this at the risk of being misunderstood, rejected, labeled and, in some cases, killed.

In hindsight, however, we often find that the prophets were right. The Hebrew prophets were right about the coming exile. Jesus was right about the fall of Jerusalem. That pattern of prophetic offense and public rejection, however, is harder to see in real-time. As the saying goes, our society hates the prophets but loves a martyr.

But perhaps it doesn’t have to be this way.

Perhaps, we can recognize the reactive, dramatic, offensive and important performances among us as an invitation to reckon with the type of society that we have.

Perhaps a hard look into some type of societal mirror can be the beginning of imagining a better society. Perhaps in the offense of the prophetic artists, preachers, activists, and leaders among us, God is speaking. “This is America” invites us to at least do the former. The question is, will we listen?