When Bassam Aragon was 17 years old, he was sentenced to seven years in prison for being with a group of friends that lobbed grenades toward Israeli jeeps.

It was his most severe crime against Israel’s military rule, but it wasn’t his first. As a child in the ancient city of Hebron in the West Bank, Aramin had raised a Palestinian flag on the school playground — which was illegal. When he was 12, he and some other students threw stones at Israel tanks. Soldiers retaliated by shooting one of the students dead.

“At that moment, I developed a need for revenge,” Aramin says. “I joined a group whose mission was to get rid of the soldiers controlling our town. We called ourselves freedom fighters, but the outside world called us terrorists.” The law called him a criminal, and he ended up in jail.

With limited options for entertainment, Aramin attended a showing of Schindler’s List—Steven Spielberg’s famous Holocaust opus. His first thought as he began watching the story of the European Jews was, “I wish they had all died. Then I wouldn’t be in this place.” But minutes into the film, he found himself crying—crying for the 6 million Jews who had been herded into the gas chambers. For the first time, he truly felt the horrific reality of Jewish suffering.

“I decided to try and understand who they were,” he say. This led to conversations with a prison guard who asked, “What makes a quiet guy like you become a terrorist?”

“You’re the terrorist,” Aramin said. “You’re the one sending settlers and soldiers here to take my land. I’m just a freedom fighter, trying to keep my village and home.”

Aramin had never considered the trauma of the Jews. His jailer, in the meantime, had never considered the sobering reality of daily life for Palestinians—one without many of the basic civil rights he took for granted.

Through their dialogue, the prisoner and guard discovered many points of contact. They listened to each other’s history and discovered each other’s humanity. Aramin was shocked and sobered to hear of inconceivable losses experienced by the Jews. Likewise, the guard acknowledged that Aramin was right—not right to use violence, but right to try and protect his home and his land. But the time Aramid was released from prison, the transformation he had seen in himself convinced him that the only path to peace was through nonviolence and dialogue that allows Israelis and Palestinians to see the other’s sincerity of heart.

In 2005, Aramin helped start Combatants for Peace, an organization of former Israeli and Palestinian fighters who decided to put down their guns and fight for peace through words and friendship, working patiently toward the day when there will be safety and freedom for both Israelis and Palestinians.

Many have given up on the idea os a pipe dream, but the peace and freedom of millions hinges on its success.

IT’S COMPLICATED

Few regions of the world receive as much global attention as the Holy Land. Its religious significnce to Christianity, Judaism and Islam—and its seemingly intractable conflict—made it continually newsworthy. For more than two decades, diplomats have tried to broker peace between the State of Israel and the Palestinians who have lived under Israeli military control for more than 45 years. For many Jews who are haunted by centuries of persecution, the inconceivable horrors of the Holocaust and the anti-Semitism that persists in many places throughout the world the security of the State of Israel is paramount. Not only do they claim a 3,500-year unbroken connection to the land, but they see the modern state as a necessary refuge in a world still teeming with deeply hostile anti-Semitism.

For Palestinians many of whom have lived under the military occupation of a foreign government since 1967 without citizenship and no civil rights freedom and sovereignty are paramount. Palestinians want to have the fundamental rights long denied and delayed in the land of their ancestry.

The relationship between Israelis and Palestinians currently is characterized by fear and distrust. With each new act of violence and additional year of conflict, the fear and distrust grow.

The conflict is one of the world’s oldest and most divisive, in which theology, politics, human rights and history are all tangled into a hopeless-looking web. The sheer complexity of the situation on this relatively small plot of land has provoked many in the West to exhaustion, if not outright apathy.

Throughout history, there have been a few crises of immense global importance ones that transcend their time and place to become parables of justice, or the lack thereof. One thinks of America’s Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, the Rwandan genocide in the 1990s, South Africa’s Apartheid.

In each, the call of Christians has been to take a stand for those who cannot. And the Church’s track record hasn’t always been great.

“The Church has played a pathetic role in dealing with conflicts globally,” says Sarni Awad, executive director of Bethlehem-based Holy Land Trust. “The Church has either been completely out of any equation in dealing with conflicts or, worse, on the wrong side of the equation.”

There is an opportunity and need for the Church to raise the global alarm for peace in the Holy Land. But the window is closing, and the situation is increasingly dire. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, who has initiated a new round of peace talks between Israeli and Palestinian leaders, has acknowledged that without rapid progress, the future will be bleak.

Daniel Seidemann, founder and director of Israeli peace organization Terrestrial Jerusalem, speaks more bluntly: “There is a war about to break out.

“We’re not necessarily talking weeks, but certainly not many years,” he continues. “There’s a war out there waiting to break out, and it just hasn’t decided where and over what, but we are living in a bubble. And that bubble will burst.”

It’s a problem that hits closer to home than many in the Church might think.

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE CHURCH?

“Palestinians are the descendants of the early Christians,” says Palestinian legislator Dr. Hanan Ashrawi. ”We are probably the straightest line to original Christianity. The Christian presence in Palestine is important. Christianity is part and parcel of the Palestinian identity.”

The modern Palestinian Christian community traces its roots back to Pentecost, representing an unbroken Christian presence in the land of Jesus since the first disciples. Today, most Palestinian Christians are Orthodox, Roman Catholic or Melkite.

There is also a small evangelical Palestinian Church, but Christians are becoming a smaller part of the population. In the land where Jesus walked and His disciples founded the early Church, Christianity’s presence is dying.

Christian faith once thrived in the Holy Land, but Christians now make up only about 2 percent of the population. And their growth rate has not kept pace with higher Jewish immigration and Muslim birthrates.

Palestinian Christians say their situation is increasingly precarious, with extremely high emigration rates due to the pressures they face. “We are the indigenous people here, and we have continued an ongoing Christian tradition,” Ashrawi says, “but pretty soon you won’t find any Christians here. The churches will become museums.”

In the West Bank, there are currently 14 evangelical churches, according to Bishara Awad, founder of Bethlehem Bible College, the only Christian college in the West Bank. “There are maybe 800 to 1,000 members in these churches,” he says. “The evangelicals are very small, a minority within the Christian community. It’s a struggle.”

Palestinians boast a high percentage of college graduates per capita, but the military occupation impedes commerce, and unemployment rates are high, so the brightest and best of Palestinian graduates are leaving the region. Many of these departing young people are Christians-they are often better educated than their Muslim counterparts and have stronger connections in Europe and the U.S.

Many who are leaving have lived their whole lives under military occupation and see no future for themselves in a place where official military policy makes the hope of a decent job and a better life unlikely.

“There are more Palestinian Christians living around the world in other places than are living in the Holy Land now,” says Todd Deatherage, executive director of Telos Group, a D.C.-based nonprofit dedicated to education and peacemaking. “The Church is beleaguered. Soon there won’t be a Christian presence here at all if the diaspora Palestinians don’t come back, or if those who are leaving don’t stop.”

And Palestinian Christians also look to neighboring Arab countries, fearing that religious and political tensions there which have largely had little expression in the Holy Land might one day bleed into their communities.

TENT OF NATIONS

One Christian Palestinian leader who has chosen not to leave is Daoud Nassar. In 1916, while Palestine was a province of the Ottoman Empire, Nassar’s grandfather bought 100 acres of land southwest of Bethlehem on a hill 3,000 feet above sea level. On a clear day, you can see from that hilltop all the way to the Mediterranean Sea, and in the evening, you can watch the distant sun set over the Jordan River. The hilltop has become ground zero for the fight of Nassar’s life-and also his quest for peace.

Nassar’s farm is surrounded by five Jewish settlements. In 1991, Nassar heard a rumor that the Israelis wanted to take control of his land to build another Jewish settlement. Unlike many Palestinians who live on land their ancestors never legally registered, Nassar’s grandfather meticulously acquired the many necessary documents to fight a legal battle. It’s a battle Nassar fought for 12 years in front of the military court, and now continues to fight in the Israeli high court.

While Nassar has not lost the land, the situation is grim. The Israeli government has prohibited all construction on the land, denied access to water and electricity, and blocked the primary access road to the farm with a massive barricade. Israeli settlers, in attempts to drive the family from the land, have chopped down Nassar’s olive trees and threatened his family and friends at gunpoint.

“So what if you have registrations papers,” he says he’s been told. “We have papers from God. He promised this land to us.”

Sitting at a long table in an underground cave at the farm hearing the story of Tent of Nations-Nassar’s project to bring people of different cultures together to build understanding and peace-one marvels at his soft-spoken gentleness. The slogan of Tent of Nations, painted on a rough stone at the farm’s entrance, is “We Refuse to be Enemies.”

Nassar explains that the frustrations Palestinians face often prompt one of three responses: they become passive victims, blaming “the other” and doing nothing to help themselves; they leave the region to find a better life in America or Europe; or they turn to violence.

“But,” he says, “we believe all people are created in the image of God, and they are not created to hate each other. So we have claimed a fourth way of action, which is the Jesus way. To overcome evil with good, hatred with love and darkness with light. This is the Christian witness needed in this area of the world.

“We have to show people that it’s possible to love your neighbor as yourself. It’s important to not just read but to live your readings. This is what we are trying to achieve here.”

Nassar and his volunteers-which increasingly include Jewish groups from Israel and even some local Jewish settlers who have been “won” by Nassar’s quiet and consistent strength choose to turn frustration and anger into positive action. Denied drinking water, they’ve built cisterns to catch the rain. Denied electricity, they’ve utilized solar energy. Denied building permits, they’ve renovated existing caves.

When olive trees have been destroyed, they’ve invited Palestinians, Israelis and internationals to come and plant new ones for peace. “An olive tree won’t bear fruit for 10 or 15 years,” Nassar says, “so when you plant an olive tree, you are saying you believe in the future.”

But what that future will look like is an issue that has caused a deep divide-even among Christians.

AREN’T WE SUPPOSED TO TAKE SIDES?

In a lot of ways, the American Church has often been more committed to taking sides in the conflict than to helping Israelis and Palestinians find peace. Differing Christian theological perspectives have turned the Holy Land into a pivot point of controversy.

American Christians hold a variety of views about the Land of Israel and the conflict. Some Christians believe the establishment of the modern State of Israel in 1948 was a fulfillment of prophecy. They believe it is a divinely mandated return of ancient Israel to the Promised Land and is directly connected to pre-ordained End Time events and the second coming of Christ.

An expression of this theological leaning is based on God’s promise to Abraham that He would bless those who bless Israel and curse those who curse it. These Christians equate the modern state of Israel with the Old Testament theocracy and, not wanting to curse Israel, use that Scripture to support the Israeli government’s actions.

“That thinking really makes no room for the Palestinian Christians, for that indigenous Church that’s been here,” Deatherage says. “For the local Christians, that’s a very hurtful and offensive thing to say that they have no place in God’s plan, in the land in which they live and the very same land in which Jesus lived.”

The other theological perspective believes the fulfillment of God’s promises to His people happened through Jesus, making the inheritances and blessings of Israel available to all believers through Christ. They emphasize that God’s Kingdom is a spiritual Kingdom, not a piece of land.

These Christians believe they “live in the New Covenant, and we are not living in the Old Covenant,” Bishara Awad says. “We live in the covenant of grace and peace, a covenant where a state is not an important thing. The Kingdom of God is more important. A covenant where the Temple is not important anymore because of Christ, the One who died on the Cross and is the last sacrifice. So biblically, there’s no need for a temple.”

Enthusiasts from both camps tend to caricature the other in broad strokes and make harsh political judgments. One camp equates supporting the state of Israel with hating Arabs. The other thinks that those who want to talk about the plight of Palestinians must hate Israel. So, far from being peacemakers, many Christians fueled by theological conviction-contribute to a polarized conversation that actually fuels the conflict.

Christians focused completely on “blessing Israel” leave Palestinian Christians asking, “Where does this leave us?” Christians focused completely on the spiritual aspect of God’s Kingdom leave Jews including Messianic Jews who believe Jesus is the Messiah but still hold to many Jewish practices feeling that their legitimate history is being dismissed.

“The theology can be debated,” Deatherage says. “You can have different views of the End Times and different readings of books of the Bible that may speak to that. But those would seem to be overridden by Jesus’ teachings that we should love our enemies, that we should do justice, that we should walk in humility and love and that we should care about Christian believers in different parts of the world. ”

So if any of our End Times eschatology, any of our theologies, come in conflict with Jesus’ commands to love and to do justice and to be peacemakers in the world, we may want to rethink those enough to make sure that we can continue to carry out that mission. Which I think is more central to how Jesus taught us to live in the world.”

That’s a sentiment shared by Ahuna Elias Chacour, an Israeli Archbishop of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church. “I beg Christians in America to stop reading the Bible in a selective way,” he says. “To select the verses that justify their own ambitions, feelings and emotions, and to reduce God to be subservient to our own wishes it would be a distortion of the Bible and God’s will. In the Bible, there is a balanced view about ownership of the land.”

Deatherage says: “Christians in America must recognize that beneath their theological-and perhaps political differences, there is a foundation of truth that every human being is made in the image of God and deserves to be protected from violence and treated with compassion and justice. On that basis, they must seek to be both pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian, convinced that when Jesus called His followers to be peacemakers, He was talking not just about inner peace, or peace between God and man, but also about peace between neighbors, ethnic groups, cultures — even between enemies.

“Though the peaceable Kingdom of God will not be fully realized until Jesus returns, believers are called to work toward that Kingdom as best they can,” Deatherage says.

THE BIRTH OF A STATE

Long before the State of Israel was established in 1948 on a portion of land in a region of Palestine, a remnant of Jews had been living in that land since Old Testament times. They were a minority population, and though they had lived for long stretches of time in relative peace with other residents of the land with whom they shared a common language and culture, they lived as minorities often do, in some measure of distrust and insecurity.

Then, in the late 1800s, as the idea of nationalism grew throughout the Western world, and as persecution of Jews in Russia and Europe increased, the long-held dream of a homeland for the Jews was fueled, and thousands of European Jews began to migrate to Palestine.

These Jews called themselves Zionists, or Jewish nationalists. And although Zionism was initially rejected as heresy, many Jewish theologians began to see God’s hand at work. After all, it was only in the Land of Israel that Jews could observe all the commandments of Jewish law. And now God seemed to be calling the Jewish people back to the Promised Land.

But Palestinians, too, saw themselves as proud stewards of that land. Many Palestinian families had been living in Jerusalem for more than 1,500 years, and Palestinian Christians claimed faithfulness in keeping the way of Jesus alive — despite eras of unthinkable persecution — for 2,000 years.

So both Jews and Arabs felt the pull of nationalism and a strong connection with the Holy Land.

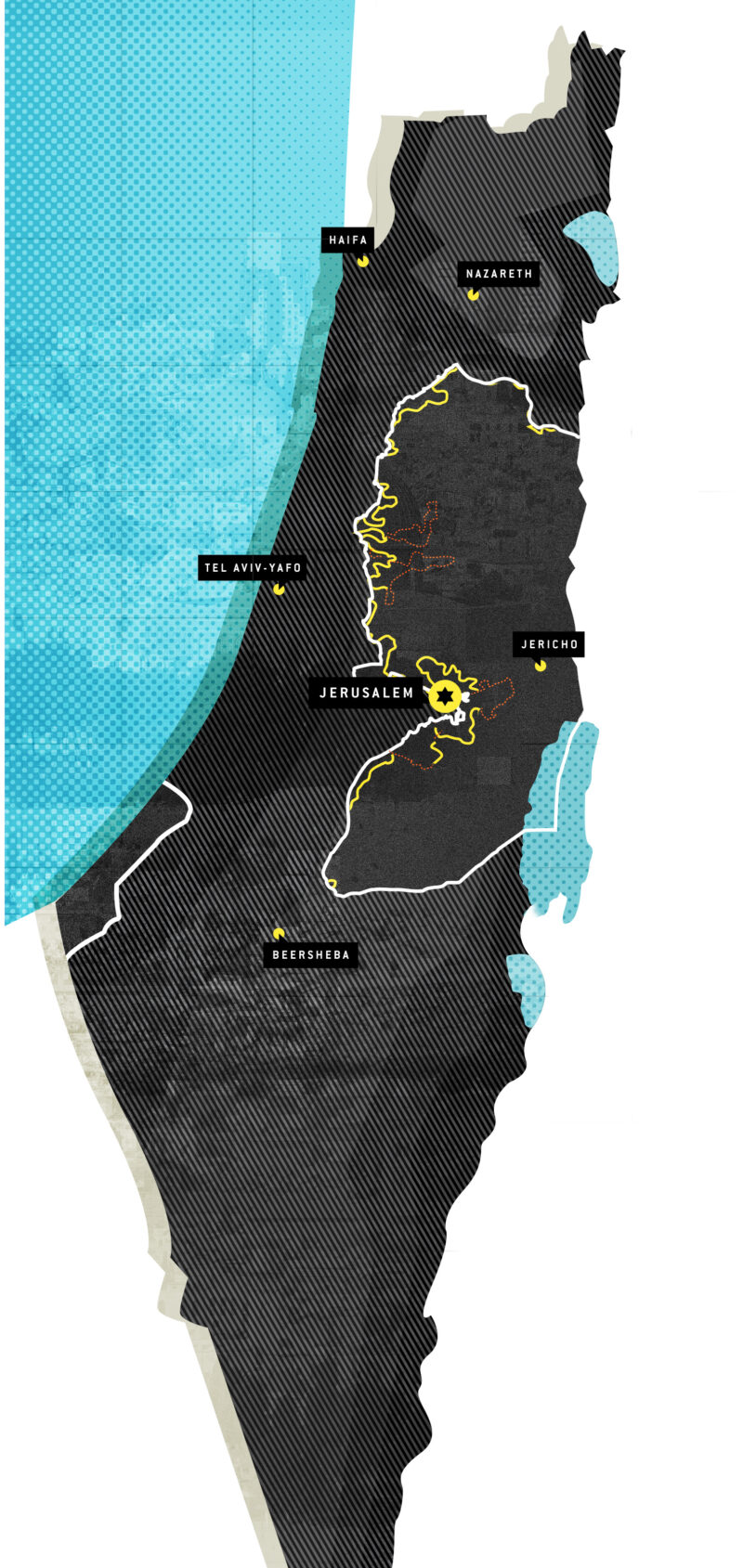

In 1947, in the aftermath of World War II and the great horror of the Jewish Holocaust, the newly established United Nations suggested a division of Palestine into two states, one for Jews and one for Arabs. This is still referred to as “the two-state solution.”

Arabs initially rejected this plan as unfair, since they were a majority of the population and were offered a minority of the land. Jews rejoiced at the proposal, seeing a historic opportunity. When Palestine’s British rulers left in 1948, Israel declared independence. Scores of countries around the world, including the U.S., welcomed the fledgling Jewish state. But the next day, neighboring Arab armies attacked Israel. Israel defended itself and prevailed. Within a year, they had taken control of even more land than had been recommended by the U.N.

It was a remarkable triumph for the Jewish people. Just three years after the last of the Nazi death camps had been liberated, the Zionist dream of the establishment of a Jewish homeland in the ancient land of Israel had been achieved. But for the Arab residents of that same land, the accomplishment was less welcome.

More than 700,000 Arab Palestinians became refugees as more than 400 of their villages and towns were either abandoned due to violence or forcibly depopulated by Jewish forces. Some Palestinians remained in the newly created state of Israel and were eventually granted citizenship rights (Arab citizens make up about 20 percent of the Israeli population today, though they do not have the full civil rights of Jewish citizens). Most Palestinians ended up being moved to the Gaza Strip, the West Bank of the Jordan River or outside historic Palestine altogether.

Between 1948 and 1967, Palestinians in Gaza lived under Egyptian control, and those on the West Bank under the rule of Jordan. Then, in 1967, Israel and surrounding Arab countries again went to war. In just six days, Israel defeated neighboring Arab armies and gained military control of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, which it still maintains now, nearly five decades later. Israel did not annex the Gaza Strip or the West Bank, so the Palestinians living there are not citizens of Israel.

“I believe in the state of Israel as a safe and secure homeland for the Jewish people,” Deatherage says. “If you look at Jewish experience in history, I think they have every right to live in a state of their own in which they’re in control and to do it in their ancestral homeland.

“But Israel also aspires to be a democracy, and to be democracy means that you have to give equal civil rights to all your citizens,” he continues. “Palestinians have a right to live in dignity and security, too.”

The crux of the “peace process” over the last 20 years has been about ending the Israeli military control — or occupation — of the West Bank and Gaza so the Palestinians can establish an independent, sovereign state. Each side-Israelis and Palestinians-blames the other for 20 years of failure.

DAILY REALITY

Because Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza are not citizens of Israel, they do not have the civil rights of Israeli citizens. However, they are almost completely controlled by policies established by the Israeli government.

What this means in everyday life is that Palestinians have limited access to local resources such as water. Israel only turns on water for most Palestinian towns intermittently. That’s why you’ll see large black tubs on the roofs of every Palestinian building in the West Bank — residents try to fill them up before the water is turned off, and then ration their supply until the next time water is available. By contrast, Israeli settlements, which are often adjacent to these West Bank villages, have uninterrupted water supply.

Palestinians in occupied territories have their ability to travel between their own communities restricted by military checkpoints, and they are forbidden to travel or work inside Israel except by permission. These restrictions that limit mobility for Palestinians sometimes separate families and often prevent farmers from tending their lands. They also severely hinder economic growth and development.

Life is also complicated for Palestinians by Israel’s ongoing settlement enterprise. Settlements are basically communities for Jews established on land inside the West Bank. Some settlements are small outposts; others are large, modern towns.

Some are populated by young couples looking for affordable housing in quiet and close-knit communities, which many settlements offer because living costs are often subsidized by the Israeli government. Other settlers are more ideologically motivated, seeking to make a religious or political point, essentially saying, “This is our land, and we will populate and claim it.” Some settlements have been built on ancient biblical sites holy to Jews, such as Hebron, Bethel and Shiloh.

Most people who support an equitable and sustainable peace agree that settlements are a major obstacle to achieving it. While settlers often claim they are living on land that was uninhabited and not owned, Palestinians see towns being built on land that was once theirs. Suddenly the trees and water rights and roads that were part of that land pass from Palestinian families to Israeli settlers. And the Palestinians look across a road or a razor wire fence to the olive trees they used to harvest or the fields they used to plow.

Many Israelis — who may or may not support the settlements on biblical grounds — argue that parts of the West Bank are necessary for Israel’s security. They note that Israel is a tiny country, at one point just a few miles wide, in a hostile neighborhood-surrounded by countries that have repeatedly waged war with Israel and have often harassed or expelled their own Jewish populations. While some Israelis vehemently oppose the settlements, many others view them as a difficult but necessary aspect of Israeli security.

WHO’S DREAMING?

While many people suggest conflict in the Holy Land “has been going on forever,” historians disagree. Arabs and Jews have both lived together peacefully and with common purposes. Many Israelis and Palestinians describe the neighborhoods where their parents or grandparents grew up in the early 1900s; while their children played together, Christian, Muslim and Jewish parents shared common values of faith, reverence for life and hospitality. In fact, many Jewish families tried to protect their Arab neighbors during the war of 1948.

Against that backdrop of peace, the violence that has marked the last century is especially heartbreaking. Neither side can claim innocence. Many people think Israel has used unnecessary military force against a demilitarized opponent. On the other hand, Palestinians who strapped bombs to their bodies to blow up Israeli civilians fueled fear and hate.

In 2003, during an era of extreme violence, Israel began constructing a physical barrier — in some urban areas it’s a concrete wall 26 feet tall, and in more rural areas it’s a chain-link fence topped by razor wire — to physically protect Israelis from Palestinians. While the barrier has not yet been completed, violence against Israelis has radically diminished in recent years. Unfortunately, so has nearly all contact between Israeli civilians and Palestinians.

For those who believe the solution to violence is not abstinence, but engagement, the wall provides a significant and literal barrier. And they have been forced to get creative in bringing Israelis and Palestinians together.

One person doing that is an Israeli grandmother named Roni Keidar who lives in the village of Netiv HaAsara on the Gaza border. In the direct line of fire for rockets launched by Gazan extremists, the small farming community of Netiv HaAsara and the nearby town of Sderot are among the most vulnerable places in Israel. Keidar knows that when the alarm sounds, she and her children and grandchildren have seconds to find a bomb shelter. She also knows that the crude rockets being launched from Gaza toward her village will be fought with the sophisticated bombs of the Israeli military. And the cycle of revenge and retaliation will continue.

So, against the rockets and bombs, she fights with a different weapon.

Using a network of cell phones, she keeps relationships between Israelis in her community and Palestinians in Gaza alive. Although Gaza no longer has Israeli settlers or military bases, the Israeli government — along with Egypt to the south — keep Gaza virtually sealed from the rest of the world. Keidar breaks this seal by connecting old friends who used to be neighbors before the barrier separated them. And whenever a Gazan receives a permit to enter Israel for medical care, Keidar meets them at the border and drives them to the hospital.

“We have to really listen,” she explains. “We’ve got to open our ears and open our hearts and start understanding one another.”

Keidar’s children say she’s a dreamer, an old woman who wants to believe that peace can come through words and understanding.

“If you think I’m the dreamer for thinking things can be different, maybe you’re right,” she says. “But I say if you think this is sustainable … no, you’re the dreamer.”

A PILGRIMAGE FOR PEACE

Each year, thousands of Christians throughout the world take a spiritual pilgrimage to the Holy Land. For Palestinian Christian Sarni Awad, his spiritual pilgrimage took him from the Holy Land to the last place on earth one would expect to find a spiritual revelation: the death camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

As an advocate of nonviolent resistance to the occupation, Awad knew what it was like to walk unarmed toward a line of armed Israeli soldiers, quietly defying the power of oppression. He knew what it was like to be pinned to the ground and handcuffed for doing nothing more than speaking.

But one day, while reading the Sermon on the Mount, Awad was gripped by words he had read hundreds of times without really seeing: “Love your enemy.” He was totally committed to nonviolence; he would not think of striking an Israeli. But love them?

Still, he couldn’t escape those words commanded by Jesus.

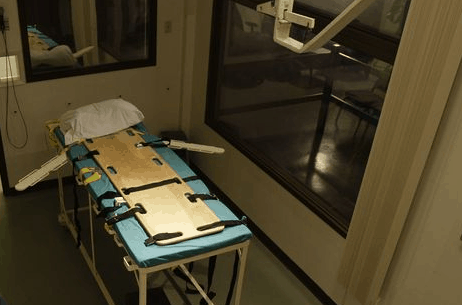

So he traveled with a small delegation of Muslims, Jews and Christians to the cold concentration camps of Poland. He and his colleagues spent an entire night in the children’s bunker — the place where Jewish children were held before being sent to the gas chambers to die.

In that quiet night of torment, still haunted by the suffering of the innocent, Awad’s heart was rent. He broke down and wept. And he prayed for the peace of Israel.

Awad returned home understanding that his enemy is his enemy because of fear and trauma and unhealed wounds resulting from centuries of racism, discrimination and violence against Jews, from the Spanish Inquisition to the Russian czars to the Holocaust — and continuing even now throughout the world, including the Middle East. Awad realized that the Israeli soldier meeting his quiet words of protest with an automatic weapon is not just an angry young Israeli who hates Arabs. He’s most likely a terrified young man fearing what might happen to him — and to all Jews — if they don’t stay vigilant and strong.

Awad has come to believe and teach that nonviolent protest with a political agenda is just one part of authentic peacemaking. Much of his time is devoted to learning and creating new ways to build trust and respect between the various communities in the Holy Land, trusting that even something as simple as a purposeful conversation can be an effective antidote to violence.

A SOLDIER’S STORY

Robi Damelin is an Israeli woman who shares Awad’s commitment to dialogue. She has lived a life dedicated to peace, with an impressive resume.

Damelin has been fighting injustice for decades. Growing up in South Africa, she spoke out against apartheid and worked actively for coexistence. In 1967, she moved to Israel — “to solve the conflict,” she says with self-deprecating humor. She ended up working on a kibbutz.

“Ever since then, I have had a love-hate relationship with this country,” she says. Damelin loves the reality of a homeland for the Jewish people, but she hates the oppression of Palestinian people that results from the Israeli military occupation.

“Israel will never be free until the Palestinians are free,” she says.

Damelin’s son, David, shared her perspective about the occupation. She claims he “would rather have gone to jail than serve in the military, but he knew that as soon as he was released, he’d just be posted somewhere else. In the end, we agreed it would be better for him to serve as an officer and set an example to other soldiers by behaving like a human being.”

David fulfilled his required service, but in 2002 he was called up to the reserves. Again, he and Damelin decided he should serve and set an example.

But as a soldier, “he was a symbol of an occupying army.” On March 3, 2002, 28-year-old David was killed by a Palestinian sniper.

“I was beside myself with grief,” Damelin says. “I had all the good things in life, but it all became totally irrelevant. I just wanted to prevent other families from experiencing this.”

To anyone who has not lost a child, such sadness is unimaginable, but Damelin was not alone. She was invited to a meeting where she met Palestinian mothers who had also lost children. “I saw there was no difference in our pain. I realized that through our joint pain we could speak out and make a difference.”

Today, Damelin is a spokesperson for The Parents Circle, a group of more than 600 Israeli and Palestinian families who have lost an immediate family member in the conflict. They join together to share their stories so they can empathize with one another and grieve together.

“Then,” Damelin says, “we can stand together on stages in schools and governments and tell our stories of loss and reconciliation.”

Damelin attends events to tell her story of losing David and her desire to help build peace. Her partner during one recent presentation was Bassam Aramin, the former Palestinian fighter turned peacemaker.

Two years after he started Combatants for Peace, Aramin’s daughter was shot and killed by an Israeli border police while she was waiting in front of her school.

Her name was Abir. She was 10 years old.

PRO-PRO-PRO

Like Damelin, Aramin and so many other Israelis and Palestinians, many are beginning to believe it is possible to be authentically proIsraeli, pro-Palestinian and pro-peace.

“Right now in the U.S. it seems like you have to fit in a box,” Deatherage says. ”You either have to be pro-Israel, which means you’re anti-Palestinian, or you have to be pro-Palestinian, which means you’re anti-Israel.

“I see that as such a false dichotomy. I think if you support the state of Israel as a safe and secure homeland for the Jewish people, then you have to also support the creation of the Palestinian state with the same ambitions that the Palestinian people to have: to live in their own state.

“If you support the Palestinians and their right to live in freedom and in their own state, you have to support that for the Jews to live in Israel. You can’t be pro-Israel without being pro-Palestinian, and you can’t be proPalestinian without being pro-Israel, and all of that is pro-peace.”

To remain a democratic state that is Jewish in character and majority, Israelis must find a way to acknowledge Palestinian demands for sovereignty in a portion of the historic land of Israel. And in order for Palestinians to achieve dignity and freedom, they must either be allowed to create their own state in a portion of historic Palestine or be given equal civil and political rights in Israel.

However the problem is resolved, many Israelis and Palestinians agree that the military occupation of the Palestinian territories is unsustainable and is a violation of human rights that ultimately hurts everyone involved. While it is up to Israeli and Palestinian negotiators to determine exactly what a future peaceful Holy Land should look like, Christians globally can and should advocate for a sustainable solution that recognizes and honors each person in the Holy Land as an equal child of God.

“When Jesus called us to be peacemakers, He was really smart,” Sarni Awad says. “He knew what He was saying. In order for us to spread His message, you cannot spread it through bombs and war and destruction. If the Church understands its role as a peacemaker, for the agenda of evangelizing and bringing Christ to the communities, then that is the approach to engage it. Peacemaking is the approach to do it. ”

A holistic approach of peacemaking will create an opportunity for real peace here,” he continues. “And if there’s real peace in the Holy Land, it will create a domino effect globally. Many, many issues will be resolved by resolving this conflict here. It will open relationships that the Church would never have been able to imagine.”

This story was the cover story from Issue 68 of RELEVANT. To see more of this issue, click here.