EXCLUSIVE

EXCLUSIVE

Already a member? log in

NO COMMITMENT REQUIRED, CANCEL ANYTIME.

Even as “SJW” has been wielded like an insult, the term itself is useful. The people who find ways to fight for justice in the social sphere have become heroes around the world—not just to those they’re helping, but to those of us who see them in action and are inspired by their stories and their courage. RELEVANT gathered a few such “social justice warriors” to get their thoughts on the last few years of global justice, and how things need to change in the future.

Over the last 15 years, what have you seen as the biggest change in how the Church has addressed justice issues?

Jeremy Courtney: Now, we care. At least, more of us do. Fifteen years ago, a huge proportion—especially those of us in the majority—didn’t. Today, churches are leading the way, in many cases, in giving their time and money and platform to educating and empowering others. It’s an indivisible part of how we understand “mission” now. That wasn’t the case for a lot of us 15 years ago and RELEVANT helped those of us at this table play a role that has transformed millions of lives. What a difference 15 years can make!

Karen Swallow Prior: Becoming a pro-life activist awakened my heart and mind to the prophetic role of the Church in the culture. What has changed in the last 15 years is that it seems many in the Church—in the face of other issues—claim now that this prophetic, world-changing role is not what the Church is about. In the past 15 years, the cry of the Church that laws must be just and justice must be pursued has sadly quieted in some corners. They say hearts rather than laws must be changed. It’s not either/or—it’s both: Both hearts and laws must change in order for us to have a more just society. And the Church has a role to play in both.

Gary Haugen: There was a time when justice work was viewed as a distraction from the “real” Gospel, as something that was political and secular, as an extra credit option or as a pet issue of a few. Now, the Church has rediscovered justice as a core passion of God and His calling to us to be His hands and feet in the world actually doing the work.

Ron Sider: There are some indications of increased concern: frequent justice conferences; wonderful growth of groups like International Justice Mission; the unanimous adoption by the National Association of Evangelicals of their public policy document, “For the Health of the Nation.” It affirms a broad, biblically balanced agenda including; abortion, marriage, religious freedom, economic and racial justice, peacemaking, and the environment. But in spite of that, 81% of white evangelicals voted for a presidential candidate that long-time Republican evangelicals (e.g., President Bush’s speechwriter, Michael Gerson, and Southern Baptist leader, Russell Moore) said was racist, sexist, dishonest and unfit to be president. It is discouraging that the vast majority of white evangelicals failed to follow the agenda of the NAE’s official public policy document.

“We must move from charity to justice.”

–Jenny Yang

Lisa Sharon Harper: The most significant change in how the Church has addressed issues of justice is that today—after Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, John Crawford, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Ferguson, Baltimore, Charlottesville, Donald Trump’s boast that he grabs women’s genitalia, the unwavering evangelical base of support that led to the election of Donald Trump, the Muslim ban, brown babies in cages, the nomination and confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh despite his likely sexual abuse of women, Trump’s support of white nationalists’ authoritarian leaders across the globe and his continued support from white evangelicals—after all of this, the evangelical church understands that how it deals with the question of race and gender hierarchy impacts its witness in the world.

Jenny Yang: Fifteen years ago when I started working on immigration issues, the white evangelical church was hesitant to get engaged too deeply, but since then, we have seen pastors preaching about immigration from the pulpit and churches developing immigrant legal services. Having relationships with people [who are] affected as well as developing a biblical worldview with a deepened theology about tough issues can be transformative in a person’s justice journey. As the Church becomes more diverse globally and in the United States, I believe that justice cannot be cast aside as a side issue but is really a core part of the Gospel.

What are some ways the Church as a whole can better address the needs of the world’s most vulnerable people?

Brittany Packnett: We can begin by recognizing that there is only one Savior—and none of us are Him. Our superiority and savior complexes do nothing to end injustice—only our solidarity does. Solidarity requires two critical shifts:

First, that we are led by those who are most affected by an injustice. We do not get to dictate the mode or the medium of freedom for others—we can only follow the lead of the vision they set for themselves, asking permission to be useful in the movement and spending our privilege to achieve the win.

Second is that we love beyond charity. Charity is food and has its place—people need to be fed, housed and fueled in the here and now. But charity is only concerned with feeding 500 people on a single day; solidarity is concerned with replacing the systems that leave 500 people hungry in the first place. Solidarity is concerned with recognizing the power inherent in those who are marginalized, and supporting them in exercising it to achieve justice and liberation.

Anything less than solidarity is a paternalistic exercise to save people who don’t need saving— they simply deserve our support.

Kristin Wright: In order to address the needs of the world’s most vulnerable, one practical step we can each take in our lives is to intentionally expose ourselves to the realities of injustice and poverty. By being present in some of the darkest, most difficult places in the world (often these places are in our own cities, even our own neighborhoods), we learn firsthand the needs of the world’s most vulnerable— and we have the opportunity to respond both as a friend and as a neighbor. Pope Francis recently discussed not just the “why” of giving to the poor but also the “how.” In an interview with Scarp de’ Tenis, translated as “Tennis Shoes,” a monthly publication with a focus on the poor and marginalized, the pope said the way a gift is given is as important as the gift itself. He challenged readers to give to the person who asks—and when we give, to touch the hands of that individual and look with kindness into their eyes. In other words, this act of giving isn’t simply about the gift—it’s about restoring something precious that is too often lost in the midst of poverty and vulnerability: human dignity.

Jeremy Courtney: We need to live it out in our own neighborhoods. It is dangerous to bop into some poor countries or places like Iraq and Syria in the middle of war—but not for the reasons that first come to mind. It’s not what they will do to us that is most dangerous. I’m more afraid of what we do to others when we, the people with the money and power, traipse through refugee camps or slums in the name of doing good. We do great harm when we try to live out our values “over there” in a way that is totally at odds with how we live at home.

Karen Swallow Prior: Our perspectives as Christians need to be more global, more historical, more holistic and more biblical. It can begin simply by listening to the vulnerable. It’s ironic for anyone who declares belief in absolute, objective truth to rely so heavily on their own individual, subjective experience in assessing the needs of our culture.

Lisa Sharon Harper: When we shift from a view of the Church that is fundamentally located in the affluent hands of white westerners to the reality of the Church that it is fundamentally located in the Southern Hemisphere in the brown and black hands of the oppressed, then our presupposition about who is vulnerable would change. We would understand it is the Church, itself, that is the most vulnerable—not people to be saved by the Church.

Shane Claiborne: Often our biggest problem is not a compassion problem, but a proximity problem. It’s not that we don’t care about the poor, it’s that we don’t know the poor. We are good at talking about people but not as good at talking to them or with them. It’s true on almost every social issue, we talk about people we don’t know —immigrants, Muslims, exploited workers … if we truly care about the issues of social justice, then the issues have names and faces.

“It’s not that we don’t care about the poor… We don’t know the poor.” –Shane Claiborne

Jenny Yang: We must move from charity to justice. Charity can meet someone’s immediate needs but justice is about power. Giving money is important and is needed as a part of charity, but giving is often done out of our own convenience and comfort, without it actually impacting how we live out our lives in relationship to others. It’s not just about teaching someone how to fish, but making sure that person has access to a place to fish and being able to fish in clean, unpolluted water as an example. We must alter systems and structures that often impact poor people disproportionately, that goes beyond meeting that person’s physical needs.

Abortion remains an important issue for many Christians. How do you hope Christians will expand their understanding of what it means to be pro-life in the future?

Kyle Meyaard- Schaap: As people made in the image of a life-creating God and followers of a Savior who proclaimed that He came to give abundant life, it is right for Christians to be concerned about abortion. Somehow, though, a large portion of the Church came to believe that a commitment to protecting life means being concerned only about abortion, rather than all other injustices that diminish and destroy life like the death penalty, euthanasia, poverty, climate change, lack of affordable healthcare, mass incarceration, police brutality, a broken and inhumane immigration system and more.

Karen Swallow Prior: Tackling something as pervasive as abortion requires a “big tent” approach that encourages many joining together in common cause despite disagreements on other issues. At the same time, working together like this cultivates mutual influence by which we can all learn and grow with one another.

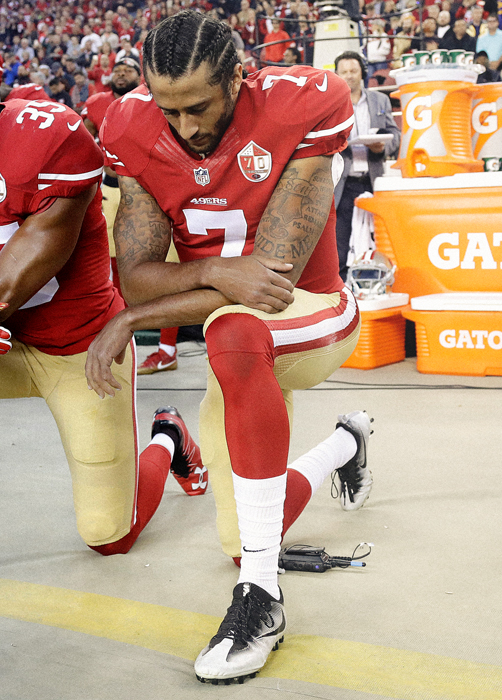

Ron Sider: If every person is made in the image of God and is immeasurably precious, then respect for the sanctity of human life dare not start and end with abortion and euthanasia (although we must work to reduce both). Millions dying of starvation and diseases we know how to prevent is a pro-life issue. So is millions dying prematurely of tobacco smoke. Black Lives Matter has called our attention to the terrible fact that many African- Americans get killed by the police without any justification. That, too, is a pro-life issue.

How can Christians most effectively address the issue of abortion?

Lisa Sharon Harper: Research has shown the way to decrease abortions is through poverty alleviation. According to a 2014 report of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops economic hardship was a prime driver of abortion rates in their 2005 study: “73% of women undergoing an abortion said not being able to afford a baby now was a reason for the abortion. That number rose to 81% for women below the federal poverty line. And while the abortion rate for American women declined by 8% between 2000 and 2008, among poor American women it increased by 18%.”

Overturning Roe would not end abortion. It would only send the decision back to states. States most likely to outlaw abortion already have the lowest populations and lowest abortion rates. States less likely to outlaw abortion have highest populations with corresponding high abortion rates. Abortion follows poverty. To diminish abortion, we must diminish poverty.

What do you see as hindering the Church from effectively addressing major justice concerns?

Karen Swallow Prior: The modern condition is one that is fragmented and atomized. It’s therefore easy for us to be momentarily outraged by cases that flit across our screens but lack the framework required to understand isolated situations within their broader, systemic contexts. This leaves us feeling overwhelmed and helpless to make meaningful change. But the same media and technology that created this fragmentation are also the ones that have helped bring about rapid, dramatic changes for example, the #MeToo and #ChurchToo movements that were fueled by social media and online communities.

Gary Haugen: A major barrier is the way Christians get thrown back and forth between a paralyzing obliviousness and a paralyzing despair. Our busy, distracted lives can leave us knowing next to nothing about a major justice issue like modern slavery. Then suddenly, we catch a graphic media exposé on the issue, we feel overwhelmed and despairing—and we do not know where to plug in to make a tangible, meaningful individual contribution.

Ron Sider: The ghastly (sinful) failure of many white Christians (especially white evangelicals) to know, listen to, live with and go to church with black Christians means that white Christians do not understand and work to end ongoing racism in our country. The intellectual dishonesty that enables many Christians to deny the science about human-induced global warming both undermines respect for Christians and contributes to our country failing to take the necessary steps to prevent likely disaster for our children and grandchildren.

Lisa Sharon Harper: How does it change how we understand Jesus Himself to understand that Rome explicitly believed in the supremacy of Western culture and white able-bodied men. In this political construct, Jesus was physically brown and politically Black. Yet, the locus of evangelical church authority to define orthodoxy is centered in the social location of the empire—within the abled bodies of white men.

Kristin Wright: Injustice is everywhere in the world, and paralysis can certainly arise from being overwhelmed by the magnitude of the problems we see. I know that feeling! That paralysis can make us feel like walking away forever … instead of staying, standing alongside, speaking out.

But when we stop staring at the size of the problem, and instead look—as Pope Francis mentioned in his guidance on giving to the poor—into the eyes of the person directly in front of us, the work of justice becomes more about the action we take in the moment, wherever we are, and less about the overwhelming magnitude of injustice globally.

Jenny Yang: I also believe an unwillingness to engage in political issues for fear of being seen as too partisan or connected to power is a hindrance for churches engaging in justice. It swings both ways, where power can indeed corrupt and distort our view of the world, but choosing not to engage at all in systems and structures that determine how our society is ordered means we are often not addressing the root causes of what causes poverty, vulnerability and violence in our world. Choosing to be apolitical is a privilege that some of the most broken people do not have. We have to engage politically without becoming partisan and be willing to work with people across the political aisle to accomplish common goals for the common good.

What’s a justice issue that Christians should be more concerned about in the coming years?

Lisa Sharon Harper: For things to be made well, two things must happen: We must reconcile America’s competing narratives and we must repair what race broke in the world. Truth-telling and reparation are both biblical concepts. They are not partisan. Reparation is fundamentally about what it takes to repair what the hierarchies of human belonging have broken in the world.

Brittany Packnett: Poverty. If the love of money is the root of all evil, we know that poverty is the very manifestation of evil. Poverty kills, poverty hurts. Poverty aligns itself with systemic racism and oppression to make cyclical suffering constant. That is not of God.

Shane Claiborne: We also have a problem with violence, and I think that is one of the demons that continues to haunt America— it goes all the way back to our foundation. Our country was built on violence—the slaughter of natives and the forced enslavement of Africans. It’s hard to get our future right until we get our history right.

Kristin Wright: Forced migration. More than 60 million people in our world today have been displaced by conflict, persecution and natural disaster. We are witnessing the greatest migration the world has experienced since World War II—and issues such as climate change and hostile borders are only complicating it.

Jenny Yang: If Jesus left all His comfort and privilege to enter into our brokenness, we have a responsibility to do the same for others. Jesus was a refugee and told us in Matthew 25 that when we welcome the stranger, we’re indeed welcoming Jesus Himself. To take His commands seriously, we must do more to create a culture of welcome and hospitality, and fight against the easy tropes, stereotypes, and denigrations of people who are leaving everything behind to find safety elsewhere.

Do you think more Christians will start to see climate change as an issue that they should be concerned with?

Kyle Meyaard-Schaap: Yes! And they already are, because faithful Christians across the world are wresting the conversation away from the realm of partisan politics and placing it in the realm of faithful discipleship. Climate change is a threat to our neighbor’s well-being and to God’s good creation, which means it also presents an opportunity for us to love God and our neighbors better. Climate action is a tangible act of evangelism because after all, Jesus told us that His message was especially good news for the poor, the imprisoned and the oppressed. Our witness to that good news is only enhanced when we take actions that result in things that are good for the poor, the marginalized, and the oppressed. And clean air to breathe and a sustainable future is definitely good news for all!

Karen Swallow Prior: China is no longer taking our plastics, landfills are reaching capacity, some cities are no longer recycling, and the thrift stores are refusing donations. Everywhere we are overrun with stuff. Whether out of necessity or awareness or both, I believe people are beginning to see the consequences of our excess. As we face that reality and begin to embrace a lifestyle of reducing and reusing, I think we will no longer have the defensive need to be in denial about the impact our actions have on the environment. Regardless of one’s views on climate change, it’s hard to deny the mountains of garbage we can’t get rid of.

How can churches get more involved in issues related to racial injustice?

Karen Swallow Prior: We need to go out of our way to equip and empower different people: men, women, black, white, brown, disabled, etc. Sometimes that will require us to move over or give up our seat at the head of the table in order to make room for other voices. I had many men do that for me, as a woman, and I need to do that in turn for others who have been underrepresented.

Shane Claiborne: Racial reconciliation must start small. We can’t expect to have diversity in our worship services until our dinner tables and living rooms change. Racial reconciliation must begin in our homes and in our lives.

What are ways that the Church can address extreme poverty?

Jenny Yang: The U.S. Church has so much to learn from the global Church about how to address poverty. In Rwanda, for example, World Relief started Church Empowerment Zones (CEZ) to empower and equip the Church to respond to poverty holistically, moving from interventions focused on community deficits and professional-client relationships to a model that empowers the community by building on local assets and professional community partnerships. With the building blocks laid and beliefs and values instilled, technical interventions become rooted in powerful scriptural support.

Ron Sider: We need to live more simply in our personal lives so we can share more effectively with good non-governmental programs combating poverty. And we need to understand national and global economic structures so we can vote in a way that promotes the right structural changes.

Religious persecution has dramatically increased in recent years. What can Christians do in the coming years to help those who feel threatened?

Kristin Wright: Religious persecution is widespread and on the rise against communities all over the world. We can help stop persecution in its tracks by first addressing the prejudice that spawns violence. And we will never be more successful at this than when we honor those who are different by giving our time, our attention, and our efforts to love and protect them. That starts by getting to know those who believe differently, and advocating for all those who face discrimination and persecution.

What gives you hope for the future of the Church?

Kyle Meyaard-Schaap: The young people I get to work with every day on campuses and in congregations across the U.S. are rejecting the arbitrary divisions that the Church has built up between worshipping Jesus and pursuing justice, and are doing it with creativity, courage and joy.

Jenny Yang: God is always at work through His people to restore and redeem the brokenness of the world, and I see young people especially engaged with a depth and a passion that I believe will help them run the marathon for justice.

Brittany Packnett: I’m made hopeful by the many voices of new groups of leaders. People like Michelle Higgins and Starsky Wilson and Traci Blackmon take the ministry to places others are unwilling, and invite those in who would otherwise be rejected. They, themselves, were once those rejected because they didn’t fit the archetype of leadership in traditional spaces. But they are willing to do the work of purpose beyond the pomp and circumstance. I like my leaders courageous. The courageous ones always give me hope.

Gary Haugen: It makes me hopeful to see a generation of Christians emerging who share God’s passion for justice and have no interest in a Gospel that doesn’t embody God’s passion for that work.

Ron Sider: The fact that Jesus rose from the dead and is now King of Kings. And the fact that many younger Christians just assume that faithful Christians should be concerned both with evangelism and social action.

Lisa Sharon Harper: I find hope in the Scripture and in the tide of history. I remember Scripture’s Genesis 1:26 declaration that we are all—all of us—created in the image of God. In the same breath God declares all humanity is created to exercise dominion in the world—to steward the world, to protect the world, to serve, cultivate and care for the world.

I remember how Jesus’ life affirmed the call of brown colonized people to defy the imposed human hierarchies of empire; woman, slave, Jew.

I remember Paul’s declaration that these power differentials are obliterated by the cross— that when we are baptized we are cleansed of the lenses of hierarchy given to us by the kingdoms of men.

All we see when we rise from baptism’s waters is the image of God in all.