New York’s Times Square—once marred by sex shops and go-go bars, and today known as a tourist epicenter—is now the scene of the latest incarnation of the Messiah. Here, Jesus has found new disciples and been given marquee-value fame in the recent Broadway revivals of Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar.

Godspell, which opened in November, is Stephen Schwartz’s now classic retelling of the Gospel of Matthew. The show, which is a perennial favorite of high schools and community theater groups, is known for its widely popular songs, such as “Day by Day” and “All for the Best” and for its whimsical treatment of the teachings of Christ. When it was first produced in 1971, it was replete with disciples as flower children and a Jesus that wore a Superman shirt and clown make-up. The current production has upgraded the once-famous hippie followers of Jesus into urban hipsters with vintage thrift-shop attire—all eager to sing and dance the night away—even if they don’t quite understand just what they are singing and dancing about.

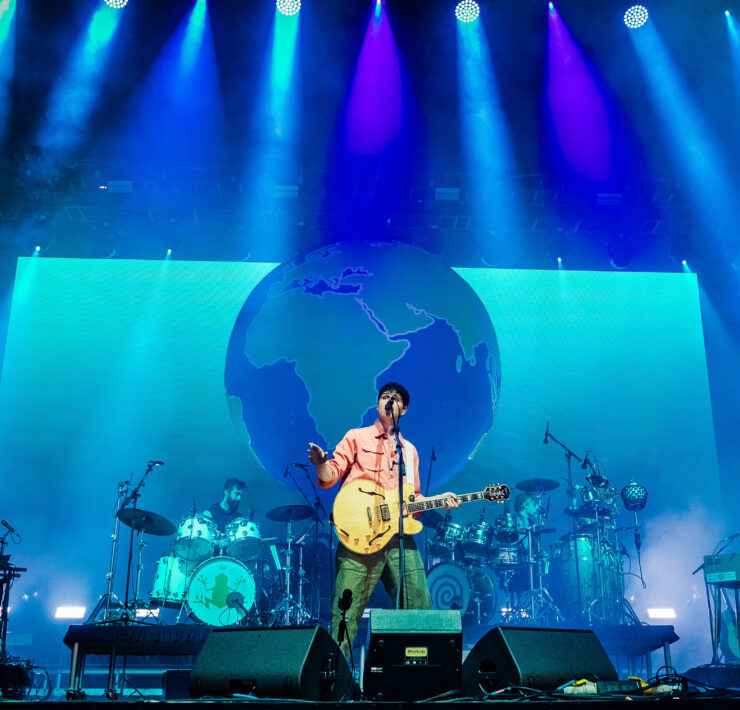

In similar fashion, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s rock opera, Jesus Christ Superstar, which also enjoyed its first New York mounting in 1971, has been resurrected in a new production that opened on Broadway in late March. Superstar began its life as a concept rock album, and for that very reason directors have long struggled with what to make of it as a stage production. While this production is held by many theater critics as the best staging to date, it presents the audience with a Jesus Christ that is certainly no superstar—in fact, He’s not even sure what to make of Himself until the closing seconds of the show, when the slightest hint of the divine manifests itself on stage.

To their credit, both productions are well-staged and particularly well-sung by young, vibrant casts. Yet despite the talent onstage, the messages of both productions remain … empty. In Godspell¸ the better portion of the show is dedicated to the retelling of the parables that Jesus communicated through charades and other audience-participation games. The second act takes a more serious turn, with reenactments of the Last Supper and Crucifixion and a finale that ends with the modern-day disciples mourning the death of Jesus and singing the lyrics “long live God” as Jesus is carried out of the theater and the lights fade to black. Even though the show is labeled a retelling of the Gospel according to Matthew, the resurrection account so clearly provided in the Gospel—and so central to the Christian message—failed to make the final cut for this production.

Superstar is set during Holy Week, and according to director Des McAnuff, his intent in this production was to focus on the supposed love triangle between Jesus, Judas and Mary Magdalene. While this love triangle is not explicitly portrayed as romantic in nature, it is, to be sure, a fabrication. Whereas the Gospels make clear the inner circle of Jesus consisted of Peter, James and John, this production features Mary Magdalene and Judas as His closest, most loyal companions while at the same fighting for His attention. Throughout this production of Superstar, which recounts the triumphal arrival of Jesus in Jerusalem, His healing of the sick and comforting of the poor, and His clearing of the temple, no one seems more confused as to what is actually going on than Jesus himself. In the opening moments of the second act, in the score’s most haunting number, “Gethsamane,” Jesus frustratingly cries out to God, sighing You’re far too keen on where and how / but not so hot on why. The same could be said of this show, which never manages to figure out for itself just why it was that Jesus took the form of a man and why this talk of death and, yes, resurrection has real significance today.

Both Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar have been met with mixed to positive critical acclaim by New York theater critics and audiences alike. While it is easy to enjoy the onstage song and dance, it is also puzzling to consider why—in a city often accused of being quick to reject Christianity—is Jesus being met with such acclaim onstage?

According to a poem written by writer Ronald Rolheiser, modern culture wants “a King but not the kingdom, a shepherd with no flock, to believe without belonging … ‘spirituality’ without religion, faith without the faithful.” I believe the same could be said for these productions of Godspell and Superstar. The appeal and good news of Christianity found in these two shows could be equated with that of Hard Rock Café’s well-known motto: “love all, serve all.” While such a message is, indeed, part of the life and teachings of Jesus, it does not accurately summarize the whole of Christianity. The message of sacrifice and self-denial found throughout the Gospels is one merely glossed over in these productions. While the real life apostles of Jesus Christ suffered actual martyrdoms and persecutions for their faith, these onstage apostles seem only willing to sacrifice a night out on the town for a chance to have dinner and play games with the new, attractive blond kid on the block.

As both a regular theater-goer and a Christian, it’s not that I found these productions to be bad shows or their messages to be entirely wrong—they are simply incomplete. The parable messages conveyed in Godspell, such as understanding forgiveness, turning the other cheek, giving to the poor and loving one’s neighbors are, perhaps, more timely than ever. The devotion of the disciples in Jesus Christ Superstar also provide a glimpse of what it means to be a true follower of Christ and, in Peter’s case, what it is like to regret the times when we deny His witness. Both of these shows provide limited glimpses of the transcendent that give us the hope of heaven. But while the hype and energy found onstage in Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar is at times invigorating and inspiring, the real life witness of Jesus espoused by Christianity provides joy that lasts long after the curtain comes down.

Christopher White writes from New York.