Since Jesus was human “in every way that we are, except without sin” (Hebrews 4:15), it is not surprising that He showed anger. His anger never ran wild, however, and anger danger was never an issue with Him.

But Jesus often got angry at His disciples, especially Peter. He got angry with the Pharisees. Jesus got angry with the priests and publicans of the temple. It is very revealing what ticked Jesus off. Of course, we are encoded beings, and human nature is not the same in all ages. If Jesus exhibited the seven basic facial expressions that correspond to seven basic emotions recognized by people from all cultures, the emotion ascribed to that face would depend on the broader context in which it occurred. What sparks anger in particular can differ radically from one age to another.

The range of Jesus’ ire is impressive. For example, within a very short period of time in Jesus’ life, three things made Him see red, and each one reveals something important about the essence of the Gospel.

Jesus’ anger at unfruitfulness

The first anger episode occurred when Jesus was on His way to Jerusalem, and He was hungry. Off in the distance, He saw a fig tree, lush with leaves. That usually meant the tree bore figs, so Jesus walked up to the fig tree to feed off its bounty. Whether the tree was in season or out of season is debated, but when the Messiah beckons, we are to be “ready in season and out of season” (2 Timothy 4:2).

But this fig tree, lush with leaves, was barren of fruit. In other words, it had been hoarding all its resources for itself. Its mission had become to look good more than to feed a hungry world and a hungry Messiah. Jesus was so angry at the non–fruit-bearing tree that He cursed it. After all, Jesus was on His way to the harvest festival (Feast of Sukkoth), which celebrates a messianic inauguration of a time of peace and prosperity when “everyone shall sit under his vine and under his fig tree.”

When God said, “Be fruitful and multiply,” the Lord was only calling us to reflect God’s nature. God is fruitful and multiplies. The fertility of the universe is amazing. The universe contains 100 billion galaxies, each of which contains 100 billion stars of incredible uniqueness and diversity. When God commanded the first Adam to till and tend the garden and to “conserve and conceive,” God was giving humans their prime directive. We were put here not to consume but to conceive.

Jesus confronted a culture of consumption, reflected in that fruitless and unreproductive fig tree, with a culture of conception. “Every good tree bears good fruit, but a bad tree bears bad fruit,” Jesus said (Matthew 7:17). Here was a tree that bore no fruit. “You will know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes from thornbushes or figs from thistles?”

Jesus said things are most reliably known for what they are by examining their fruit. Jesus called His disciples to be more than faithful—He called them to be fruitful. Jesus wants to taste our fruit. The fruit of a tree is that tree come to consciousness. The fruit of a human life is that human coming to God consciousness. When there is nothing to taste, there is no consciousness in that life. And this does not make Jesus happy.

Jesus’ anger at those who damage children

If you want to really make Jesus mad, however, so mad that He could sound more like the mafia than the Messiah, then damage a child. A wifeless and childless Jesus was the biggest patron and protector of children: “If you harm one of these little ones, better for you that a millstone be draped around your neck and you be dropped into the depths of the sea” (Luke 17:2). Or in the secret language of Omertà, “Better you sleep with the fish.”

It is hard for us to imagine how low on the social scale children stood during Jesus’ day. The ancient hierarchy of reverence, with father first, mother second and child always last, was flipped on its head with Jesus and the Holy Family, where the story revolved around the child, then the mother and the father somewhere to be found if you looked hard enough.

What made Jesus turn the social hierarchy upside down and place children at the pinnacle? Maybe it was Jesus’ haunting realization that before He would die for us, a lot of children (firstborn sons) died for Him in Herod’s slaughter of the innocents. Or maybe Jesus’ tenderness toward those for whom culture had no room stemmed from His sensitivity to being born when there was no room for His mother to give birth to Him. In the parable of the good Samaritan, there is a surprise ending based precisely on these lines. The innkeeper makes room for the distressed traveler and gives Him intensive care. Jesus knew from His mother’s stories what it meant for people in need to have no place and no advocate.

When the disciples debated who among them was the greatest, Jesus took a page out of Isaiah 11:6 (“And a little child shall lead them”) by plopping a little one in their midst and saying that the greatest reality was in front of them. Jesus was not denying ambitions for greatness. He didn’t rebuke the disciples for wanting to be “the best.” But He reframed the nature of greatness and “the best” in terms of little ones’ capacity to love, to live out of love and to humble themselves out of graciousness. You want to aspire to true greatness, to being best? Then make yourself small. Become a “little one.” The maximum is found in the minimum.

Followers of Jesus are all “little ones.” Childhood is not something you grow out of but grow into. “There will be no grown-ups in heaven” might be the best translation of Jesus’ words in Matthew 19:14. But even more than showcasing a child (not some adult scholar or soldier or priest or businessman) as His model disciple, Jesus made a child the primary metaphor for following Him and for holiness. The greatest gift of Jesus was the “right to become children of God.”

Jesus’ anger at self-righteous judgmentalism

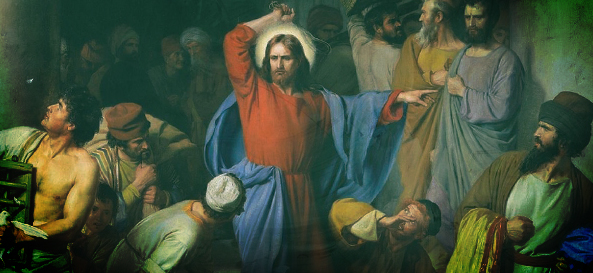

The third anger episode that makes Jesus’ inner life less mysterious to us is His “temple tantrum.” As He drove out the money-changers from the spaces normally dedicated to prayer for Gentiles as well as Jews, overturning their tables and ATMs, He cried out the words of Isaiah: “My house shall be called a house of prayer for all nations.”

What is “My house”? The “house” is God’s temple, and in the Hebrew tradition the temple and the garden are different ways of talking about the same reality.

For Jesus, the “house” is the same, but the definition of the temple is more precise: the temple of the church, the body of Christ, and the temple of the person, as in “your body is the temple of the Holy Spirit.” Two of the most shocking events in the Second Testament, Jesus and the money-changers and Peter and the money-cheaters, are both cleansing rituals. When Jesus said, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up,” He was telegraphing the upcoming transition from the temple as a place to the temple as a people. And just as there was a temple cleansing just before the closing of the placed temple, there was a temple cleansing (Ananias and Sapphira) just after the opening of the peopled temple.

Something else made Jesus absolutely livid and was perhaps His greatest irritant: self-righteous judgmentalism. Survey those to whom Jesus directed His strongest, most severe words. It was the self-righteous, judgmental Pharisees and Sadducees—those who didn’t see themselves as sinners but who leveled that charge against everyone else. He characterized such people as “blind guides,” “hypocrites,” “fools,” “whitewashed tombs,” a “brood of vipers” and children of the devil.

Not exactly kind words from a mild-mannered Messiah.

And to whom did Jesus show the most compassion? People who were involved in immorality of all types, such as prostitutes, adulterers, tax collectors and thieves. It’s easy for us today to acknowledge that Jesus treated the self-righteous more severely than the “real sinners” without applying this standard to our own context—or to ourselves.

But “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever” (Hebrews 13:8). What He deemed to be the severest of all sins (self-righteousness) is what many contemporary Christians view as a mere misdemeanor. And the sorts of sins toward which Jesus had great compassion and patience are what many Christians place at the top of the totem pole of “serious sins,” deeming them to be felonies.

Don’t be deceived: the “odious complacency of the self-consciously pious” is what infuriated our Lord the most. Philip Yancey was dead-on when he said that some Christians get very angry toward other Christians who sin differently than they do.

Excerpted from Jesus: A Theography by Leonard Sweet and Frank Viola. Copyright ©2012. Used by permission of Thomas Nelson, Inc.